The expression “tendencies in art” is typically used to depict artistic currents or trends – in terms of form, subject, style or any other aesthetic dimension. However, in the ex-Yugoslav region, it also involves certain historical connotations ranging from socialist-style censorship (accusations that an artwork or art movement promotes “bourgeois or other anti-socialist tendencies”) to significant art movements like the New Tendencies (where the term tendency refers to a willingness take different course of action, another direction, and so on). However, in the broadest etymological sense, the Latin noun tendentia is derived from the verb tendere, meaning to stretch, stretch out, extend, and apply tension (coming from the same etymon). Like in archery, this involves putting tension on a string and arching the bow in order to shoot an arrow at the desired target. The word tendency thus refers to a motion in a certain direction, implying an effort to make things go towards a certain goal. On the other hand, in everyday speech the word tendency refers to something that is not yet fully visible or clearly discernible, something that has yet to develop completely. It is this eminently active, purposeful and practical, yet undecided, dimension of the term “tendency in art” that I find well worth tackling.

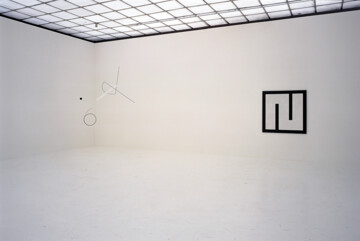

Vjenceslav Richter (New Tendencies), “An Object as a Space Subject. Reflections on Exhibitions”, 1968 & Juraj Dobrović, “Spatial Construction”, 1966, in the Low- Budget Utopias exhibition, Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova, Ljubljana 2016. Photo courtesy of Moderna galerija, Ljubljana. Courtesy Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb.

The term tendency is not even remotely new. Nevertheless, what is historically changeable does not mostly involve the words themselves, but the meanings they convey. In most cases new terminologies are made out of “borrowed” words from other fields of knowledge. Maybe what is involved in coming up with a new vocabulary or “language” is precisely the → estrangement of the existing terms – taking them from one familiar context and transposing them to another. So, my invitation to rethink the notion of tendency would be to disengage or suspend the usual meaning of the word in the sphere of art (in the abovementioned sense of currents or trends), and to infuse this term with the meanings mainly connected to Marxist discourse (ranging from theoretical and political connotations to the verbiage of everyday life under socialism) in order to see how it works and to try to make it useful for us today.

Instead of embarking on such an ambitious task, I would rather allude to those meanings of the word tendency while presenting some of the reasons – especially one connected to an exhibition-making project – that led me to choose to deal with this term in the field of art. As a member of the Prelom Kolektiv, I actively participated in a long-term regional → collaborative research project, The Political Practices of the (Post)Yugoslav Art (2006–2010), about the cultural – artistic and political – heritage of the socialist Yugoslavia. However “retrograde” this project may seem, it had a more or less articulated theoretic-political background in the Belgrade-based journal Prelom. The term “prelom” can be translated in a broad sense as a break, implying a physical act of breaking, but in a specific sense, Prelom took its meaning from Althusser’s concept of coupure, rendering it a synonym for an impossible and yet necessary notion – revolution. Stemming out of an educational project by the Belgrade Soros Center for Contemporary Art in the late 1990s, the editorial board comprised mainly of art history and sociology students who had the opportunity to develop and further galvanises the existing artistic and theoretical, cultural and political networks across the former Yugoslavia. The PPPYuArt (Political Practices of (Post)Yugoslav Art) project involved WHW (Zagreb), kuda.org (Novi Sad) and SCCA/pro.ba (Sarajevo Center for Contemporary Art), and later included other artistic, theoretical and political groups.

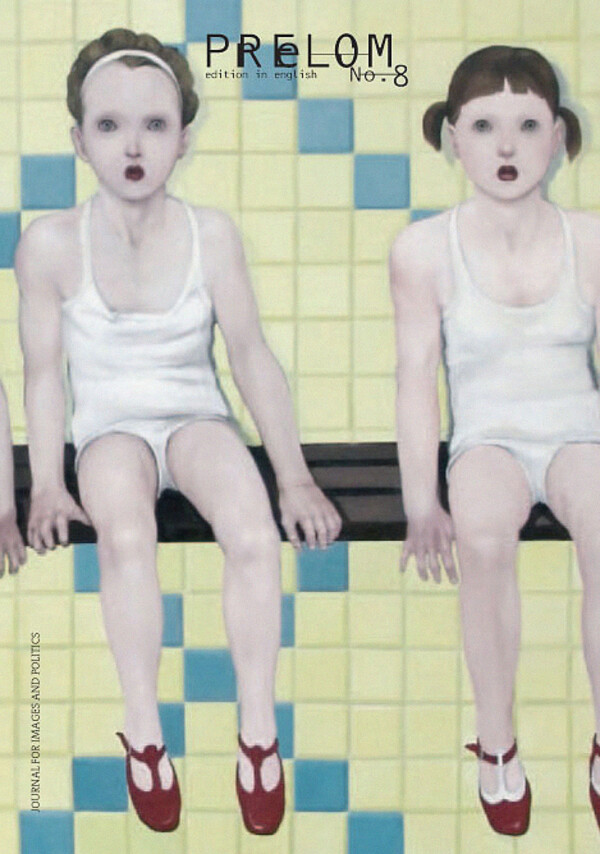

Prelom. Journal for Images and Politics, no. 8, 2005, magazine cover.

For me, the inspiration to articulate the general outlines of this inquiry within the Prelom Kolektiv was the 2007 Kontakt exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade – showcasing the Erste Bank’s collection of East European neo-avant-garde and conceptual art. The artworks were presented in a curatorial and architectural setup that embedded them within a very well-known discourse. The ideological outlook of the exhibition suggested a convenient story of the “brave artists” that fought for the freedom of expression in the midst of totalitarian communist societies, therefore ultimately creating a narrative that legitimises the current neoliberal situation after the so-called democratic revolutions and transitions to free-market economies. The main idea was to struggle against those ideological → representations of the socialist past by making (self-) educational case-study exhibitions that would offer tools for revealing the historical, social and political contexts of the artworks or art concepts and movements.

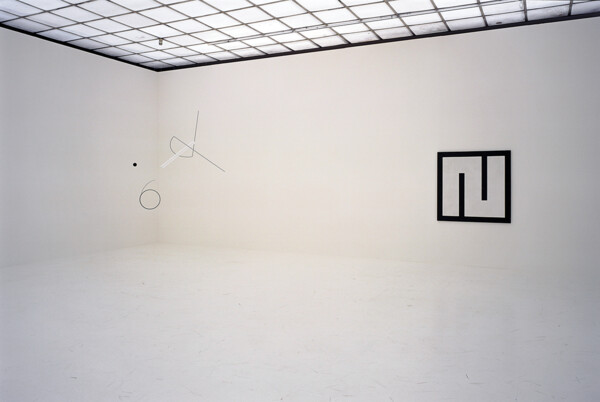

Kontakt, exhibition view, Museum of Contemporary Art Belgrade, 2007. Courtesy of Kontakt. The Art Collection of Erste Group and ERSTE Foundation.

It was precisely the development of this project that sparked the idea of revisiting the notion of the term tendency in art, since it enables a broader and more illuminating perspective on the historically variable production of art’s meaning and effectivity. The elucidation of historical contexts allows for the insight that the tendency of an artwork or art movement could significantly differ in diverse historical, political and economic circumstances. For instance, while the tendency of conceptual art was founded some 35 years ago on the critique of artwork as commodity (revolutionising the art form by depriving it of a fixed object and making it in fact just a communicated idea, bodily gesture or something else that could not be easily materialised as a thing that could be bought and sold), the tendency of the same conceptual artworks as exhibited in Kontakt becomes a willy-nilly apotheosis of the present neoliberal condition (especially in terms of the ongoing economic transformation that favours the circulation of immaterial commodities as the source of profit). Therefore, inquiring into and discerning the tendency of art involves radical historicisation: questioning and revealing the determinants of aesthetic, cultural, social and political contexts of the meaning – or the effects – produced by art. Since the meaning (or effectivity) of art is always an outcome of the forces operating in a particular institutional context, the research based on the notion of tendency can become an active power on the socio-political battlefield of art.

Now, this can easily be understood as some neo-Nietzschean war of interpretations, or even as a post-Marxist discursive class struggle. In the case of the PPPYuArt project, it might have been just like that, since the strategy was to → intervene in the ongoing production of art history, and, hopefully, of history in general. Moreover, in order to get out and be present on the relevant “battlefields”, the collaboration with and funding from the Erste Bank Stiftung was welcomed. This enabled the publication of the 2009/2010 PPPYuArt final exhibition catalogue that was supposed to deliver a left-flank blow to the ideological discourse of East European art. Nevertheless, it was quite easily digested by the ongoing historicisation processes, leaving us wondering if we did, in spite of our enthusiastic criticism, just add to the process of value production, unwittingly enabling with a colourful publication the continuation of art historical discourse construction under the auspices of the bank’s funding and its auxiliary bodies (the Erste Stiftung also has a network of transit galleries)? The true materialist lesson thus teaches that efforts to “reveal” or, conversely, to “determine” the socio-political tendency of an artwork does not take place only on the discursive battlefield, but at a more rudimentary level of social institutions and the political economy that determines them in the last instance.

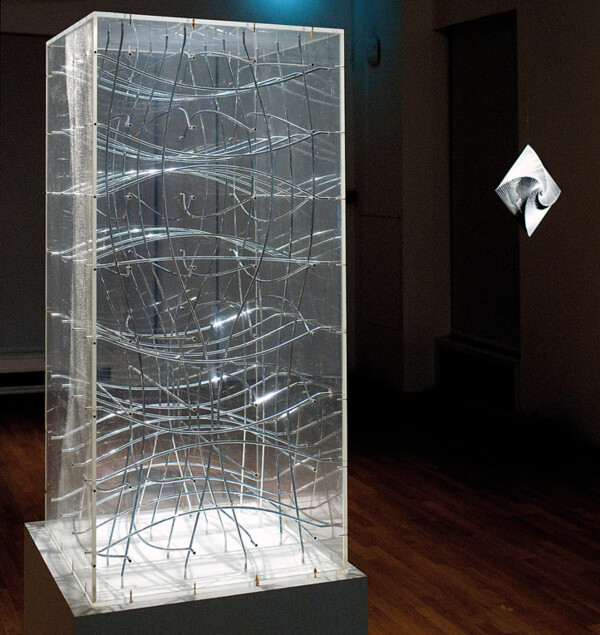

Political Practices of (Post-)Yugoslav Art (PPPYuArt): RETROSPECTIVE 01, “Chapter 6: Two Times of One Wall. The Case of SKC in the 1970s”, curated by Prelom kolektiv, exhibition view, Museum 25th of May, Belgrade, 2009. Photo: Vladimir Jerić Vlidi (flickr.com/ photos/vlidi, CC BY-SA 3.0).

Hopefully the term “tendencies in art” can thus be used as a starting point for a broader discussion on the relations between art and politics, ideology and the political economy of art, in different local contexts as well as in the broader global one. In general, one speaks of tendencies when one really wants to map the → constellations → constellations of forces that carry out certain agendas, in this case in the field of art. But the tendencies in art can only be properly discerned and actively dealt with if they are considered in their interplay with the ongoing historical changes in the cultural, political and social relations of production. Maybe today it is much more difficult to distinguish and determine historically new tendencies, since there is no general sense of what should be mainstream or institutional art, and, moreover, what could be a viable alternative to contemporary predatory capitalism. Perhaps detecting and aiding some transformative tendencies in art (those that seek to change, transform and revolutionise the very institution of art – its practices, meanings, and power relations, its social significance, its political economy), can open perspectives for a broader social transformation.