The starting points: The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) from the perspective of cultural politics; the role culture played in the movement; the importance which was placed on cultural politics and its embedded emancipatory content; the art solidarity networks within the movement; the active role the public played in culture.

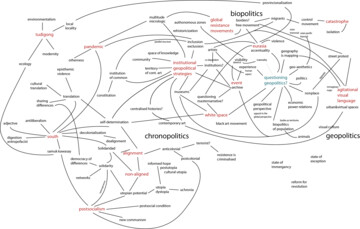

Key questions: What to learn or extract from the movement today, what kind of future strategies can be applied for creating a different kind of international constellations in the field of culture? What are the possibilities for debating the “space” of NAM in our current situation, with a diversity of once prosperous anticolonial thoughts and ideas? How to interconnect the fields of culture and political engagement, as well as solidarity?

Very early on, more specifically at the Cairo Conference in 1964, the NAM made cultural equality one of its most important principles. This meant, on the one hand, that a number of African and Asian nations sought to regain the artefacts/works of art which were taken out of their countries during colonial times and put in various museums in New York, London, and Paris; and on the other, that people who were denied their culture in the past started to realise the emancipatory role culture played in their lives, or, in other words – its transcultural potential. The cultural development of → decolonising countries became as important as their economic development. But the fact was that this culture was not supposed to be only for the elites anymore, and that in the new constellation art should be accessible to all.

Already at the 1956 UNESCO Conference in New Delhi, shortly after the Bandung Conference, representatives of so-called Third World countries (or “the South”) dedicated themselves to promoting alternative routes of cultural exchange from those adopted in the Second and First Worlds.[1] For example, these alternatives could be observed in the new waves of biennials that sprung up in the countries of the NAM, appearing in Alexandria, Medellin, Havana, Ljubljana, Baghdad, and so on. This was a way to pursue politics by other means, and these alternative modes of cultural exchange clearly showed the sincere attempts at cultural independence being made after the independence of many new nations.

Yugoslavia fit well into the discourse of non-alignment, and was a key member from the very beginning. Socialist revolutions had a lot in common with anti-colonial and anti-imperialist revolutions, which made the Yugoslav case of emancipation in the context of socialism particularly significant. The NAM provided an opportunity for positioning Yugoslav ideology and culture globally on the basis of the formula: modernism + socialism = emancipatory politics. As A. W. Singham and Shirley Hune and put it: “It was Tito who has revealed to the Afro-Asian world the existence of a non-colonial Europe which would be sympathetic to their aspirations. By bringing Europe into the grouping, Yugoslavia helped to create an international movement.”[2]

The concept of non-alignment became the main component of Yugoslavia’s foreign policy very early on. President Josip Broz - Tito – travelled to various African and Asian countries on so-called “Journeys of Peace” (for example, his famous visit to Western African countries on the Galeb (Seagull) boat in 1961) to support the independence of post-colonial states. These trips subsequently acquired a strong economic dimension and created new spheres of interest and exchange among countries of the NAM. This intense economic collaboration at first included Yugoslav construction companies working on projects in Africa and the Middle East (Energoprojekt, Industrogradnja, Smelt, etc.), → construction companies that had sprung up as a consequence of the fast urbanisation of Yugoslavia after the Second World War. Such companies provided everything, “from design to construction”, including architecture and urban planning. One of the first such cases was the building of the Kpime Dam in Togo in 1961, after Tito’s visit to the country. Some younger architecture scholars are currently looking into the development of this kind of “non-aligned modernity” from a new perspective. Dubravka Sekulić[3] researched the ways Yugoslavia and the decolonised countries in Africa became unexpected allies in the process articulating how to be modern by one’s own rules, i.e., how to direct one’s own modernisation. Such examples, as mentioned above, were the architectural and urban-planning projects in various African and Arab non-aligned countries, like Energoprojekt’s Lagos International Trade Fair (1974–77). Here, architects combined Yugoslav socialist modernism with tropical modernism and the local contexts. These ideas were eagerly accepted in the newly independent non-aligned countries and here we can paraphrase Achille Mbembe (and the concept of “worldliness”) and say that it was important not only to generate one’s own cultural forms, institutions etc. but also to translate, fragment and disrupt realities and imaginaries originating elsewhere, and in the process place those forms in the service of one’s own making.[4]

Yugoslavia extensively used its specific geopolitical position not only in the economic sense but also, as we have seen, in culture. I already mentioned architecture as a state-promoted vehicle of new modernist tendencies compatible with the idea of creating a new socialist society. These ideas were also in line with similar issues that non-alignment frequently addressed; such was the question of cultural imperialism. At the 6th Conference of the Non-Aligned Countries in Havana, Tito spoke of a successful aspect of the Non-Aligned Movement, the “resolute struggle for → decolonisation in the field of culture”. Interpreted from today’s point of view, this struggle also included new kinds of → historicisation, rewriting historical narratives or even writing history anew. In other words, the emphasis was put on questioning intellectual colonialism and cultural dependency. The idea was therefore not only to study the Third World, but to make the Third World a place from which to speak!

From the late 1950s on, Yugoslavia had special relations with the newly independent countries in Africa, and in a specific way all these networks led to a “recolonising” of the continent by means of socialism’s newly established connections in the NAM. Exchanges of all sorts happened in the field of the arts and education, as students from non-aligned countries came to study in Yugoslavia, and Yugoslav museums acquired various artefacts, with the Museum of African Art opening in Belgrade in 1977, as a result of this ideological and political climate. This not only impacted ethnographic museums, but also museums of history, such as the former Museum of the Revolution of the Yugoslav Nations, which became the steward of a large number of artefacts/gifts that President Tito received on his travels in the non-aligned countries. This era also saw the “birth” of a specific travel literature about “exotic places”; the most prominent example being the work of Oskar Davičo, a surrealist writer and politician, who visited Western Africa during preparations for a NAM meeting. He wrote a book about the journey called Black on White[5], in which he analysed the post-colonial African societies of the time. His analysis is probably one of the most interesting interpretations of the new world order from two perspectives: from the position of an artist/writer, and from that of somebody who himself was coming from a non-aligned country.

Ljubljana (International) Biennial of Graphic Arts, exhibition view, 1955. Moderna galerija Archive.

There is also the case of the Ljubljana (International) Biennial of Graphic Arts, which was first held in 1955 at the Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, and this event was linked to the non-aligned cultural politics of the day. The founder of the biennial was Zoran Kržišnik, a long-time director of this institution, who saw the event as a possibility “for a projection of values such as the presence of freedom, modernity, democracy, openness and so on in society”[6]. The biennial was set to introduce abstraction in the art world in Yugoslavia and to prove that even “fine art can be an instrument of a slight liberal opening”. Kržišnik noted in an interview that he showed President Tito that the biennial of graphic arts was in fact a materialisation of what was being referred to as openness, which was then seen as non-alignment.

One important aspect of cultural politics in the time of the NAM was the existence of solidarity movements and networks in the arts and culture, which were especially present in the 1970s: mostly as forms of political engagement against imperialism and apartheid, supporting struggles for independence, and so on.

Museo de la Solidaridad, permanent exhibition view. Courtesy of Museo de la Solidaridad.

One example would be, if observed retrospectively, the Museo de la Solidaridad (Museum of Solidarity), established in 1971 in Santiago, when Chile was non-aligned. The concept for this museum was the → common idea of two people, the Chilean President Salvador Allende and the Brazilian art critic Mário Pedrosa, then an exile in Chile. This idea later expanded into an international network of artists, critics and curators, including Harald Szeman, Dore Ashton, and others. After President Allende wrote an open letter to the artists of the world in 1971, donations from all over the globe started to arrive in Santiago, with around 600 works alone being given in the first year of the museum’s existence, in a wide mixture of styles: Latin American social realism, abstract expressionism, geometric style, and Informel, along with more experimental proposals and conceptualism. The act of donation was a political action in itself, and considered as a statement of political and cultural solidarity with the Chilean socialist project. However, this museological experiment ended abruptly with the military coup in September 1973.

Subsequently, the entire 1974 Venice Biennial was dedicated to Chile, setting up murals instead of exhibitions, and organising performances and concerts. This edition was perhaps the largest and most resonant cultural protest against Pinochet’s rule at the time.

Or another example, the International Art Exhibition for Palestine[7], which opened in the spring of 1978 in Beirut. Organised by the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), it was comprised of around 200 donated works from nearly 30 countries. The collection was destroyed in 1982 by the Israeli military during the attack on Beirut.

But I am not mentioning these cases as examples of the exoticism of the past, even though the NAM is today considered more or less a political anachronism. Moreover, we should not be entrapped in a nostalgic notion about the movement itself, as we know there were many states in the NAM that were quite far from the principles the movement promoted. Additionally, the concepts of nation states, identitarian politics, and exclusive national cultures could also be problematic, if interpreted from today’s point of view. And what should one do about the fact that Syria, Pakistan, Libya and the majority of African states are still members of the NAM?

Nevertheless, there are numerous positive aspects of the movement that should not be forgotten. It envisioned forms of humanism that took as their starting points the lifeworlds of those peoples and societies forcibly placed on the margins of the world economic and political system. The struggles against poverty, inequality, colonialism in the world system, as well as trans-national solidarity, which took on many concrete forms, could be part of a reconsideration of the history and legacy of the NAM today, when colonialism is again becoming ever more evident. However, this reconsideration alone is not enough, as it is necessary to find common points of resistance and struggle against exclusion from equal participation in decision making, from free access to common goods and resources, from free movement, from participation in knowledge production, the use of common heritage and so on.

A modest proposal is that this could also be done, in the field of culture, through various networks, alliances, museum federations, like L’Internationale, knowledge production tools like this Glossary, and various solidarity movements, with these not only consisting of cultural operators, but also joining forces with social movements, grassroots organisations, migrants, and many others.