“Family” was one of the finalists among the nominees for word of the year 2016 in Slovenia, organised by Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts (other finalists words were refugee, wire, precarious, Trumpism, uberisation, recycle, participle, approximation and health). It seems that the idea of the family persists, uninterrupted, still strong. In the 1960s and 1970s, people called for sexual liberation and lived in communes. They found out this was just another family. Then the 1980s and 1990s came, and the familiar family returned. We hoped that this would be a return with a difference. The family is here, as sickness incarnate, ironically strengthening the idea of the family even more. So instead of inventing new terms, I would prefer to reread an old one. The family is here as structure, model, metaphor, as place of origin and point of no return, as an institution. Do we need to save the family, or to destroy it? Do lines of descent still make sense for artists, or have networks taken their place? From the nuclear family to the queer family, from the commune to neopatriarchy, it lives on in many forms. We understand different things when we try to define “family”.

For example: America’s first family – not the Trumps, but the Kardashians. Robert Kardashian is best known for being the lawyer that defended O. J. Simpson. Kris Kardashian’s second husband, Bruce Jenner, in one of the greatest media spectacles of our time, who divorces Kris and undergoes male-to-female transition to become Caitlyn Jenner. The world’s attention is on this family, which has redefined what family business means. The family is a real-estate issue; it is within its architecture – within its specific organisation of space – that desire is allowed to flow. Has the family improved even a little since Freud? Can hysterical sickness still be seen as a site of resistance? Is there any space for hope? The spa no longer offers an escape from the family house: it is the house, it is the family. What the Kardashians seem to prove is that anything goes in the family as long as the family is strong.

Speaking about a strong family: the definition of the family became one of the main tasks of the ex-Yugoslav → postsocialist countries. A constitutional referendum was held in Croatia three years ago. The proposed amendment to the constitution would define marriage as being a union between a man and a woman, which would create a constitutional prohibition against same-sex marriage. A total of 38% of voters took part, and 66% of them voted yes. The referendum was called after a conservative organisation U ime obitelji (On Behalf of the Family, established in Croatia in 2013 to “promote family values and to protect dignity of the family”) gathered more than 700,000 signatures demanding a referendum on the subject. The initiative was supported by conservative political parties, the Catholic Church as well as by several other faith groups. In Slovenia, Družina (Family), is a weekly Roman Catholic magazine, launched in 1952. A referendum on a bill legalising same-sex marriage was held in Slovenia a year ago. The bill was rejected, as a majority voted against, with the votes against representing more than 20% of registered voters. Earlier in 2015 the National Assembly passed a bill defining marriage as a “union of two” instead of a “union of a man and a woman”. Conservative opponents of the law, including a group called Za otroke gre (Children Are at Stake), gathered enough signatures to force a referendum on the issue. Unfortunately, here family is not one of the institutions abandoned by the state.

But let’s leave this discussion and create different → imaginations. Almost all amateur photography begins with family photos. However, many fine-art photographers also focus on family subjects. It seems that there is no family without children, even Nan Goldin, known for intimate and uncensored photographs of her circle of → friends whose lives revolved around drink, drugs, obsession, joy and death, sometimes couldn’t resist this topic.

Figure 1: Jusuf Hadžifejzović, Čarlama (Fear of Drinking Water), performance, clothes, easels, graphics Fear of Drinking Water (1994). (The performance has been staged in Rome, Belgrade, Sarajevo, Pula, Podgorica, Seul, Antwerp, Dubrovnik, Split, Prijepolje, Zagreb, Maribor.) Courtesy of the artist.

In a grand family photograph that was taken at the Cetinje Biennale in Montenegro in 1994, members of the family of Jusuf Hadžifejzović and his friends gathered for the first time after three years of war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In this project, Hadžifejzović once again implemented his idea of creating site-specific installations. The war in Bosnia and Herzegovina raged that year, and the artist came from Belgium, where he lived as a refugee, to Montenegro, where he was invited as an eminent artist. Instead of looking for material in depots in Cetinje, he asked the Biennale organisers to invite to the exhibition all the members of his large family who had, for years, been living there, in a sort of “hostile territory”, as second-class citizens. What else could Hadžifejzović do in Cetinje but exhibit his “deposited kith and kin”, which was so much in tune with the spirit of his art? This photograph has become a basis of a continuous performance through the years that followed. (Figure 1) It was followed by some other family photographs, including friends and statements.

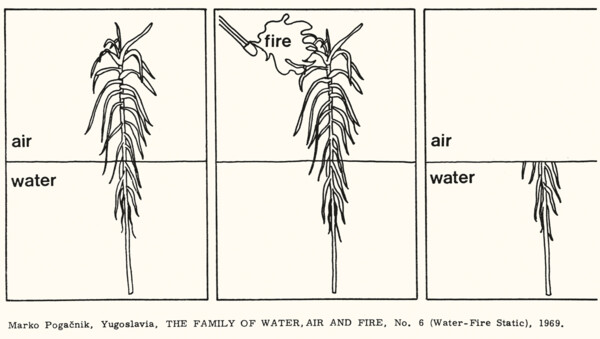

Figure 2: Marko Pogačnik (OHO Group), Family of water, fire, air and earth: water – fire static, 1969. Courtesy of Moderna galerija, Ljubljana.

According to Marko Pogačnik, a member of the group OHO, the relationships within the family can be either static or dynamic. For example, within his project Family of Water, Air and Fire (1969), it is dynamic if the interaction between three components of the works (fire, water and air) caused a process or transformation to occur. The elements in his projects were connected in dynamic, functional, and mutually defining relations that Pogačnik described as “family”. The real “subject” of these works was not their immediate materiality, but the relations and transformations of the materials used. (Figure 2)

Some examples will help us understand this type of work better. In “Water-Air Static”, for instance, Pogačnik filled a number of plastic bags half with water and half with air and put them in a river. The part of the bag where the water remained below the surface, while the part with the air remained above it. In Air-Water Dynamic, however, he filled the bags only with air. He attached weights so they would stay in water, thus creating a tension between the water and the air in the bag that was trying to rise above it.

In Water-Fire Dynamic, he set fire to a plastic bag filled with water. The result was air (carbon dioxide and steam) and plastic residue. These works were presented through documentary photographs and conceptual drawings that explained the relations among the elements and how they developed.

The abstract and conceptual aspect of his work is even more obvious in his next “family” project, called Family of Weight, Measure and Position (1969). From the title itself, it is obvious that Pogačnik was dealing with relations, not materials. He was demonstrating the → interdependent connections of three types of relations. The clearest example is a work in which Pogačnik hung a series of different weights to lines that ran across razor blades. The position of each blade was different, depending on the size of the weight. His → interest, clearly, was in general – and therefore abstract – relations; in principle, it would have been possible at any time to re-install different projects from the series or even to replace them with a sketch, since it was the basic relationships that formed the “content” of the works, and these can be grasped only conceptually. It was with these works that OHO, in fact, entered the realm of conceptual art.

In March 1971, the OHO artists, along with their families, took up residence on an abandoned farm in the vicinity of the village of Šempas in the Vipava Valley in the western part of Slovenia. The Šempas Family, as it was called, was founded on ideas that had been developed during OHO’s last period. The main idea was to discover a way of life based on balanced relations within the family and between the group and its more or less immediate contexts.

The decision of the OHO group to form a commune and thus expand its artistic practices into the broader field of life and work turned a number of things upside down. Everything (along with art) was now of equal importance: all areas of everyday life, agriculture, and the beginnings of a spiritual centre. At the outset, the commune had 12 members (two of them children). The will to carry on with artistic work soon proved to be illusive and unrealistic due to the amount of work required around the house, stables, vineyard, garden, and fields. As a result, most members of the former OHO group left the community in the following few months. A series of articles published in the magazine Mladina helped the commune out of this crisis, as young people came and joined it.

Artistic work was resumed two years later in the form of Pogačnik’s concepts of art as collective work in which all members of the commune participated, including the children and random guests or visitors. There was a School of Drawing and mobiles were made, comprising the four elements. The commune chose a name for itself as an artist group only when it was invited to publicly present its life and work: The Šempas Family. The decisive input here was the root of the Slovene word družina (family), which is družiti se, to come together.

The members of the commune were deeply involved in meditation, breathing exercises, and similar esoteric practices. Drawing was a daily ritual, and the drawing style was directly connected to the standard reistic drawing from the early 1960s, while the subjects of their drawings were plants and other things found in their everyday life. They produced objects using traditional crafts, which represented their life in a concentrated way, revealing it as the intersection of many circulating nets and processes. They used conceptual drawing to present relationships. Instead of geometrical shapes, Pogačnik began using more organic forms – circles, spirals, and curves that indicated the processes, their circulations and connections. The Šempas Family dissolved in 1979 when it became the “ordinary” family of Marko Pogačnik.

It seems that Pogačnik did with the notion of family what IRWIN did with the state. Instead of the typical leftist refusal of those traditional institutions, it seems that today we need even more state involvement. The same we can say for the family: the only way to prevent radical conservative takeover of the family is to take it seriously and practice our own versions and definitions of it.