The loser is the flip-side of the neoliberal subjectivity story, the tarnished back of the gold-medal in the all-encompassing race to capitalise upon the self. The loser is one of the possible outcomes in the constant compulsion to organise one’s life as an enterprise, in which the main commodity for sale is oneself. In the on-going contest of the market economy of the self, the loser is the one who didn’t win, who could not, who gave up, who got exhausted, who became depressed, who found him or herself alone... the one who lost.

His or her fate has to do with an individual failure: s/he did not play her/his cards well, did not make the right choices, the right investments, the right moves. S/he was personally unable to conform to the social norm of success and regular happiness and thus deserves our pity, but not much more: in the neoliberal world of equality of opportunity, we are all responsible and in control of our own destiny. Our future is entirely in our hands, it only depends on our individual efforts, our talent, our insight. Bye-bye to any collective account, any link established with backgrounds, circumstances, contexts, let alone structural relations of class, race or gender... Tales of heroes who come from the bottom and end up rich and happy are there to tell us that anybody can triumph if s/he strives enough – the American Dream comes true.

However, neither failure nor victory are definitive: the wheel of fortune goes on and on. Both winner and loser are thus unstable positions – there is always a chance of falling, an opportunity of picking oneself up again and getting back into the game. In the psyche of the entrepreneur of the self, the loser is therefore that Other whom the winner must foreclose in order to keep playing and enjoying the game – the ghost who haunts his/her nightmares, who reminds her/him that s/he can fall from grace, the one who invokes the fragility of her/his own success, the costs of the competitive race in one’s life and in the lives of others (what about all those who fell on the way?). Both a spur and a source of fear and guilt, the loser is the spectre of → fragility that the winner has to exorcise time and again in the everyday battle to keep his/herself in the market game.

Several means are deployed to accomplish this exorcism: coaching techniques, self-help books, pharmacology and frenzied consumption come to the aid of the entrepreneur of the self, calming anxieties, containing panic and providing hyper- identities and readymade affects to cling to. They pick up the baton from old Fordist institutions that no longer offer support, recognition or protection to increasingly individualised individuals, all too lonely in a complex and risk-ridden world.

So understood, the loser is not just a person who had bad luck in life and may need a little help from somebody, be it the State, a charity or his/her community. Nor is it a stance to occupy and resignify, as a marker of resistance to the hegemonic subject, because it is itself → constitutively inherent to it − the loser never exists by him/herself but only in relation to its opposite, as that inadmissible shadow which the winner both needs and rejects. In the context of competitive normalisation, both winner and loser are ways of staying stuck in the mode of subjectification which make us entrepreneurs of the self.

If there should be resistance in the sphere of subject formation, where indeed the neoliberal technology of → power has a major field of application, a move outside such frame is required – one which might help us to subtract ourselves from the winner/loser dyad as a dreadful alternative. The good news is that such moves of subtraction are already happening, everywhere. Here are two possibilities at hand:

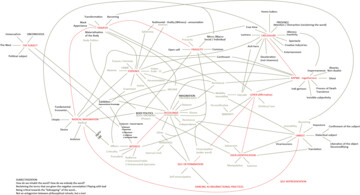

Figure 1: In 1994, hundreds of European artists, activists and pranksters adopted and shared the same identity of Luther Blissett.

First, becoming anyone, enjoying the subtle liberation of not being anyone in particular, willingly abandoning the unceasing (and exhausting) capitalisation of the self. The politics of anonymity are one good example of such a becoming: in the 1990s, many artists and activist all over Europe and the Americas took faceless or multiple-use names, such as Luther Blissett, as a way out of the competitive commodification of the self, already installed in the world of art. (Figure 1) Such a gesture was also a means of acknowledging that creativity is always a matter of the many, that the brilliant idea doesn’t belong exclusively to the genius, but has a lot to do with being embedded in rich social environments and feeding on them.

The occupied squares movement (including the Arab Spring uprisings and the worldwide Occupy movement) offer a recent and slightly different example of the same becoming. The people in the squares didn’t have anonymous voices, they did talk in their own name, but not in an attempt to make a big name for themselves – they did so to make their voice heard, as one specific voice among many, as a particular grain in the pomegranate of the square, not detaching themselves from the multitude, but joining the singular and the → common in what was called a politics of anyone.

The second move away from the winner/loser dyad is also very much linked to the experiences of the occupied squares, and it has to do with → care as a daily activity which sustained the movement. Care presupposes a break within the neoliberal logic, which urges us to be individually responsible for ourselves, enclosed in our egos, caught between the narcissistic enjoyment of our personal successes and the shame for our personal failures. The usually invisible activities of care reveal the fallacy of the self-made man, the independent healthy and young adult who appears on the earth ready for adventures, relying only on his own strengths. They show to what extent we are part of the ecosystem we are embedded in, and how care for the self is inseparable from the care for others and the environment, as the Indonesian concept of → kapwa shows us.

Figure 2: Yo Sí Sanidad Universal, Vigilia Jeanneth, 8´ 47˝ video, posted on YouTube on 6 November 2014. Filmed by Cecilia Barriga. A performance of carezenship Todas somos Jeanneth [We Are All Jeanneth] in memoriam of Jeanneth de los Ángeles Beltrán Martínez, who died because of the decree-law excluding migrants from the national healthcare system.

Historically, in the Western world, care has been enclosed within the private walls of the household. In the context of neoliberal hegemony, it has been charged with a negative connotation, being experienced as a costly burden on carers and as a humiliation by those who need to be cared for. Nevertheless, new social movements are increasingly recognising and practicing care in the public sphere, as a general social function, necessary to build a different and less predatory world. They encourage us to put care at the centre of our practices and thoughts as a major foundation for citizenship (carezenship), as primary social bond, as imperative to take charge of the unsurpassable horizon of human → fragility and → interdependency. In doing so, they show us a promising way out of the neurotic self of late capitalism. (Figure 2)