Against democratic optimism

Disappointment, as a functional experience, can be thought of as the opposite of what Laurent Berlant[1] described under the category of cruel optimism. The latter refers to a particular type of affective economy in the technologies of contemporary governability, that is, a form of disciplined affectation in neoliberal societies through which people choose to bond with objects of desire through historically predetermined hopeful promises and joyful images, that hold them bound to the fantasy of morally superior futures, even against their own well-being, for the sole purpose of giving continuity to their existences under the therapeutic effect that comes from following the right path, the path of normative guidelines that prescribe what can make these lives better, what can make them good lives. Through this category, Berlant names the way in which these forms of optimistic attachment wear down fantasies of mobility and progress, creating problematic bonds with such objects of desire, thus demonstrating how the promise of happiness described in turn by Sara Ahmed, that semiotic architecture that works as an invisible guide orienting the experience of the existent, can be revealed as impossible, mere fantasy, or directly dangerous, risking the lives of those who dream.[2]

As a counterpart, disappointment is a feeling that can potentially symbolise the loss of the hopeful attachment that neoliberal democracies institute as a condition of possibility to access a happy future, revealing through sensations of breakdown, fraud or disenchantment, the systemic, productive and profitable features of the self-destructive emotional contract that imposes on us the need to maintain at any cost a bond with that object of desire – in this case, a good life, a democratic life – in order to avoid its loss, since the mere possibility of its absence or any attempt to deviate from the righteousness of its path threatens, in one way or another, to end our own life and society as a whole.

In this sense, to become disappointed – that is, to voluntarily or accidentally practice a negative reaction to the falsehood, insufficiency or directly the failure of that neoliberal promise that instrumentalises our attachment – can turn into an oppositional consciousness[3] capable of accelerating through uncomfortable emotions a collective critique of the cruelty inherent in contemporary regimes of global governability. These regimes operate under the internalisation of a radical individualism and a practical realism determined by the rhythms of supply and demand, that are multiplied even more by the work of artefacts that extend the soporific power of magical voluntarism, that dominant belief that David Smail recognises as the unofficial religion of contemporary capitalist society.

From the year 1983, an important part of the tensions that characterised the recovery of the democratic order in Argentina can be found prefigured in a series of conflicting presences within a time that, → after seven long years marked by the organised terror of the civil-military dictatorship, embraced the public space to begin the feast of democracy, along with the newly elected president Raúl Alfonsín. Also known as the Democratic Spring, this process did not condense a homogeneous yearning for institutional reconstruction, but a polyphonic series of political strategies to make it concrete. In other words, it not only instituted a legal way out of authoritarianism, but simultaneously invoked the strength of all the struggles for political freedoms, representing in itself the possibility of the realisation of different imaginaries of social transformation.

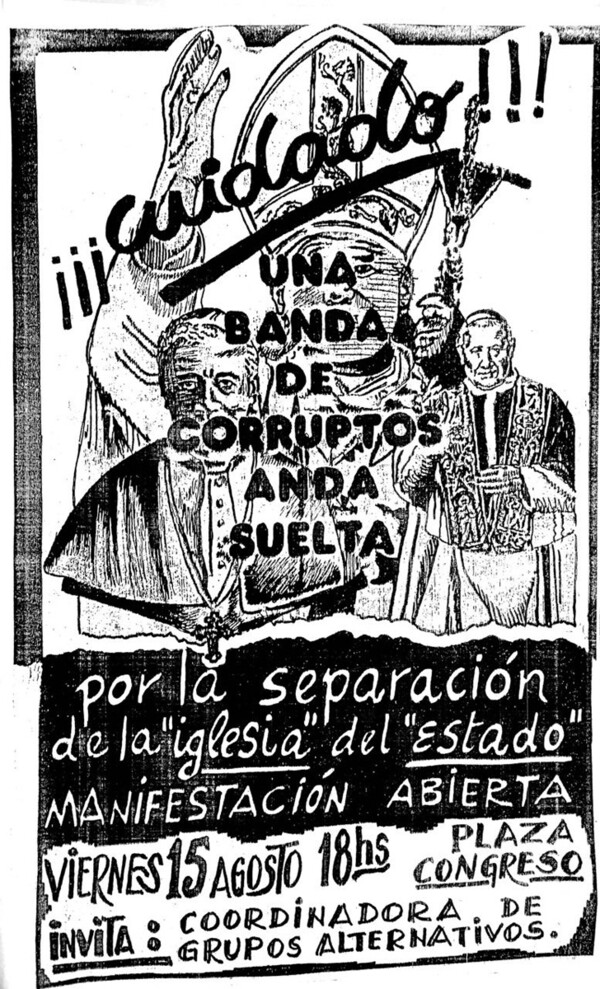

Therefore, when understood as a polemic signifier[4] the hopeful promise of Argentine democracy resided precisely in its ability to become a form of → imagination of the social whose meanings never ended up fixed in a predetermined way, but were worked out through the twists and turns of historical disputes. Some of these tensions were materialised in a group of micropolitical experiences and non-organic initiatives of collective organisation, such as La Marcha Pagana (Pagan March), promoted by La Coordinadora de Grupos Alternativos (1986), and the Malvenida a Juan Pablo II (The Repudiation of John Paul II) organised by La Comisión en Repudio al Papa (Commission of Repudiation of the Pope, 1987) a gathering of groups that shared a political affinity which through their differences sought to make visible the repressive persecution faced by all those subjects involved in the strange design of other ways of living during the return of democracy to Buenos Aires, and also aimed to denounce the leading role played by the ecclesiastical institutions in promoting the repressive sexual morality that justified these types of violence. (Figure 1 and 2) These actions were carried out by dissatisfied gay activists, anarchist magazine editors, melancholic leftists disappointed by their parties and a prolific series of street graphic action groups, young punks, heavy metal fans, underground performers and → feminists, all organised against police edicts. As political spaces, they were strongly nourished by their constitutive differences, and it was from their activities designed a particular way of doing defined by a deep criticism of traditional modes of political action. They thus prioritised protest under affective registers that operationalised the force of ridicule, the unravelling of pleasures and the loss of meaning as an experience of the critical subjectivation of the public space.

Figure 1: Marcha Pagana [Pagan March], 1986, poster, photocopy, 35.6 x 22.9 cm. Design by Club de Blasfemos [Blasphemous’s Club], Biblioteca Popular José Ingenieros.

Figure 2: Marcha Pagana [Pagan March], 1986, poster, photocopy, 35.6 x 22.9 cm. Design by Club de Blasfemos [Blasphemous’s Club], Biblioteca Popular José Ingenieros.

Against sacred marriage

Through a series of meetings that took place in a cultural space related to the Humanist Party, the Coordinadora de Grupos Alternativos (1986), a gather of alternative groups mostly formed by → queer activists and anarchists, gathered to discuss how they could intervene in the current climate against the Divorce Law, that was once again marked by the violence of the police and the media pressure in support of the religious discourse, giving shape to the initiative of La Marcha Pagana: a rally convened for 15 August 1986, at Plaza Congreso in Buenos Aires. The principal vector for the organisation of this was the demand for the urgent separation of Church and State, but it would be different from other proposals because it celebrated the exercise of absolute freedom to achieve it as its absolute horizon. Through flyers filled with drawings made to the rhythms of a raunchy camp[5], a type of hypersexual representation that juxtaposed the poetic density of punk graphics, the use of pornographic images and a vast universe of blasphemous signs, the movement’s protagonists cheerfully called for the occupation of public spaces while dressed in the ragged costumes of nuns, priests and altar boys, aiming to blind the military gaze with the gender-fluid extravagance of a multitude of bodies drunk on cheap, flashy gemstones, but also with the smelly mohawk of angry punks and the artisanal vests full of rusty chains from young metal fans who sought to undermine the social call to normality.

The rally landscape was completed by an uncontrolled abundance of posters that denounced the Church’s complicity with State terrorism, rejecting the forthcoming visit of Pope John Paul II, while also mocking the local clergy with a strongly sarcastic tone. A series of banners attempted to disrupt the transparency of these explicit demands by introducing onomatopoeias (Oh, Uh!, Ahh!) on a large scale that graphically reproduced a confused mix of roars of awe and pleasure. Meanwhile, two giant puppets functioned as escorts to all the ridiculousness that occurred at the event’s peak, until the → crowd were brutally repressed. On the one hand, there was a stick marionette of a nun whose robe mechanically revealed some prominent, satiny pubic hair and pointy nipples smeared with glitter; and on the other, there was a puppet mounted on stilts by Gustavo Sola that tried to represent the Argentinian macho ideal, and whose long foam penis was carried like a → dead animal. From the liveliness of their irreverent expression, these homemade artefacts activated a pagan force imbricated with anti-repressive desires, in a coven that linked the inorganic agency of those uncontrollable subjectivities that aspired not only to the recovery of the night, but also to interrupt the fictitious promise of citizenship that had inaugurated the return of democracy, altering the rhythm of the common through sexual misconduct.

Enrique Yurkovich, one of its principal promoters of this event, says that the strategy of occupying the public space through sexual provocation, ridicule and extravagance, was aimed to antagonise the ongoing political practice of ecclesiastical power at the national level: the Public Masses in Defence of the Family for the faithful, featuring children and adolescents in public squares. Claudia Zicker, an anarchist activist and founder along with Yurkovich of the initiative Club de Blasfemos (Blasphemous's Club), an imaginary association that operated through subscription coupons placed inside the magazine Manuela (1986), comments in an interview, on the decision to occupy the public space with this overgrown, particular affective energy:

We thought we could be monsters in the street. We wanted to position ourselves within this discussion, but not from the discourse of the democratic family that we considered phoney. We wanted to detach ourselves from that political culture of normality. We weren’t going to dress up as decent people asking for a divorce, that’s what they were for. We addressed it from a different side. If the Church has a say in this matter it is because the Church and the State are jointly operating, and this is a secular country. That is why the process of forming La Marcha Pagana meant we had to learn about the constitution, and the history of religions. We were prompted to test democracy, to ask about that limit. That’s why we proposed the legal separation of Church and State.

The experimentation with the limits of democracy would not only be a quest regarding strictly the institutional interference of the Church over the State, but had also become the bodily principle from which participating spaces within the Coordinadora de Grupos Alternativos made politics. In the words of their members, their desire was to distance themselves from phoniness, since they distrusted politics as they knew it and thought the only truth was when things happened through the body. That not only implied the idea of “use the body” – that is, to inscribe it materially in the manifested multitude – but it was also a matter of turning it into the possible language of all political expression. That is the reason why the physical appearance or dress style as public devices of subjective singularisation[6], along with nuances and the sexed and gendered design of gestures, were all part of an integral program for those new modes of political action.

In the face of clerical power, the usual misfits cheered loudly for divorce, the consumption of pornography, the excessive use of drugs and the free exercise of sexual deviance in the city streets, but the problems did not take long to arrive. → After having occupied Plaza Congreso, they started spontaneously singing slogans with the background sound of off-key instruments, and then they decided to walk in circles around the square, as had learned from Madres de Plaza de Mayo and the Human Rights movement with which they held a direct affinity, and which many felt themselves a part.

But in the midst of that dissonant coven, pressured by the appearance of fundamentalist Christian groups who had attended the rally to perform a “collective exorcism” on these youths driven by sex, drugs, and blasphemy, the police began to surround the perimeter where the mobilisation was taking place in an attempt to disperse it. As time went on, the proximity of the police escalated into a delirious confrontation that irritated those who were there defuse the situation. The dialogue that follows is one of the few available registers of what happened that day, and faithfully represents the main features of a new principle of political organisation based on mockery, delirium and the intoxicated intensification of the senses, as recalled by the people who were there in their testimonies:

‘Who is the leader?’ [a policeman asked]. ‘There are no leaders; the leaders have died’, a 50-year-old replied. ‘Who is responsible for this?’ ‘We’re all irresponsible’, a punk said caustically. ‘That puppet is obscene; you are violating the 128 of the Penal Code.’ ‘Haven’t you heard of grotesque art?’, they responded. In the midst of the repression, the police are still clueless, and the protesters start shouting without backing down: ‘We want to fuck!’ It is incredible: we are in Buenos Aires, it's 1986 and two hundred frenzied people are shouting WE WANT TO FUCK at the corner of Callao and Bartolomé Mitre.[7]

The discussion about the grotesque and obscene, the outlandish language from which the activists challenged the patience of the officers, the prankster replies and the ways in which they tried to outwit power gave them time to resist, but ultimately failed to contain the repressive fury that would ensue. Struggles, beatings and persecutions brought to an end the pleasure principle from which that small crowd of misfits aimed to affect reality.

The few testimonies from which this episode has become known agree that the only strategy to resist the possible advance of the police was nudity: “The urgent thing to do was to run and lose our clothes on the way. That was the only way they wouldn’t recognise us,” remembers Claudia Zicker, in our personal dialogue. The police detained fifteen protesters, with approximately two hundred participants in the event reported in the public media. Human rights organisations said that those detained were victims of brutal police repression, the same as in the worst days of the dictatorship, while the police argued the main reason for stopping the demonstration was the open displays of sexuality that infringed on public morals and were obscene, and thus the expressive repertoires of protest that were used.

Describing accurately what had happened, the official statement shared by the Coordinadora de Grupos Alternativos concluded by calling for a second La Marcha Pagana, but the momentum of this mass blasphemy would quickly fade over time. Even its historical value would experience a similar fate. In tension with the available language of leftist activism as well as the affective repertoires of the incipient gay pragmatism,[8] even today it is difficult to gauge the contribution that an event like this had, especially due to its abrasive critique of democracy, but also for its absence of records, the inconsistency of its organisational methodologies, the imprecision from which it is remembered and above all, the political devaluation associated with its ephemeral nature.

From the shared concerns among the different types of groups that had formed the Coordinadora de Grupos Alternativos, whose political affinity was strengthened after La Marcha Pagana and especially after the repressive onslaught they had faced together, it was possible to instil in the discussions of that time a sense of urgency to dismantle the social ties of clerical power in the weightless management of the new democratic reality in Argentina, through experimental antagonistic → imaginations. Although, in formal terms, that collective organising body had found its limit in the past experience all of its members, along with a significant number of new activists, editorial teams, political parties, cultural organisations, sectors of the human rights movement and independent artists, all of whom joined in the Comisión de Repudio al Papa (Commission of Repudiation of the Pope, CRAP): a call outlined under the subversive resonances of La Marcha Pagana that took public form with the publication of the manifesto entitled “Contra Wojtyla” (“Against Wojtyla”), signed by the artist Jorge Gumier Maier and the writer Enrique Symns from the editorial team of Cerdos & Peces in the magazine’s issue no. 9 (February 1987):

We have enough evidence accumulated in our sensibility, experience and perception of the world to state that the Pope, the present one or any other, represents one of the powers that control human existence in the West. Throughout history, the Church he represents has been one of the most dangerous and cruel pests that have scourged humanity. It was there in all the massacres, participating, giving their blessing, dividing the spoils, concealing and assenting, always at the victor’s side, with an evasive and uncompromising discourse at hand […] On April 6, the Pope, the same Holy Father who in the Malvinas will line up on the Reagan-Thatcher axis, is coming to Buenos Aires with the intention of ‘blessing this democracy’. We are calling all good-willed souls who wish to give an effective, legal and eloquent response to his message, to join us and prepare a great event where we can raise our hand and say NO to his presence. […] Repudiation, on the other hand, must be considered as an inalienable right granted by the constitution to express the thought of a group of citizens, and therefore it is the intention of this proposal that nothing illegal, rude or injurious be done. Contact us.[9]

While the epistemological substratum that organised the repudiation continued to be the incandescent expression of disagreement over ecclesiastical power and its effective participation in the continuity of conservative regimes of cultural control, this call, unlike their previous experience and at least in enunciative terms, sought to avoid the possibility of any conflict or contempt that might confront them with a possible repression. Some of the protagonists say this was one of the main discussions during the meetings that would structure the organisation of such an event. All the issues of security, legal remedies and anti-repressive containment strategies, as well as the expressed will to expand the repudiation of repressive systems without any conditions, were installed as needs to address in the process of assemblies that took place at first in the editorial office of the magazine Cerdos & Peces located at 2537 Corrientes Street, but eventually due to two bomb threats they would move to the Parakultural Center and later, to the José Ingenieros Popular Library.

With a decidedly more organised rhythm, the groups that formed the CRAP called in the Plaza del Obelisco a massive rally for the day 3 April 1987, in which they sought to express a wide repudiation to the Pope, the actual representative of a power historically involved in the extension of restrictive principles of control towards social behaviour and, especially in Latin America, a power that had participated in the crimes against humanity perpetrated by military dictatorships. Having learnt from the public discomfort and flamboyant informality of initiatives such as La Marcha Pagana, on this occasion the call had a clear programme of cultural activities that included the reading of poems, political documents, performances, and concerts in which the most relevant precarious stars from Buenos Aires’ underground were involved. At the same time, this program was part of an extensive series of cultural activities that the members of CRAP had produced individually from their particular spaces, as a prelude to animate the impulse of rejection with regard the Pope’s arrival. Many of them were held in the most representative spaces of libertarian organisations in Buenos Aires of the time: the José Ingenieros Popular Library and the Federación Libertaria Argentina (the Argentine Libertarian Federation). These were spaces that housed young anarchists engaged in the organisation of conferences, film series and plays that thematised the hidden history of religious power in the reproducibility of capital and its continuous pressure on the sexual behaviour of society.

Days before the official call, in every corner of the emerging underground scene of the post-dictatorship proliferated ephemeral associations, reduced affinity groups and fictitious organisations that implemented identification and → disidentification strategies[10],produced graphic materials and tools of agitprop calling for participation in the protest against the arrival of Pope John Paul II. Some examples of this type of action: Claudia Zicker and Gustavo Sola, anarchist activists and impatient workers from the underground disorder, distributed flyers outside → schools, during their rounds of bars and within the reading groups in which they participated. These were handmade flyers that showed a significant number of asses drawn with simple pencil strokes, juxtaposed with the face of John Paul II cut irregularly from some xerographic printing of the time. Signing this call as C.U.L.O – Comando de Unidad Libertario del Oeste (Command of Libertarian Unity of the West) – they ironically invited the ingestion of puré de papa polaka (“mashed Polish potatoes”), transforming the Obelisco in the venue of a free buffet in which diners could taste the irresistible flavour of the radioactive potato, referring not only to the recent Chernobyl nuclear accident in April 1986, but to the collective organisation that had taken shape in that country to express its total rejection of the arrival of the same Pope who was trying to make his way through local misery.

For his part, Miguel Ángel Lens, a marginal poet and one of the leading activists of San Telmo Gay, distributed his own flyer under the fictional name of Grupo Antiautoritario “Los pinchados” (Anti-authoritarian Group “Los Pinchados”), inviting people to participate in the March of Repudiation against the Pope. Under slogans such as “the poem does not protect me, poetry does”, “religion is a cosmic electric prod”, “property is theft” and scattered fragments of personal poems, he drew with the delicacy of his naivety a young, contemporary face full of decorative attributes, whose graphics erotically touched the drawings of Jean Cocteau and Sergei Eisenstein, intervened by the ornamental saturation of a camp more linked to punk dissonance than to the decadent glamour of the locals’ melancholic sensitivity[11]. Around it, the iconic anarchist symbol with a capital A was scattered, almost like the onomatopoeias of a mental chant. These initiatives were also accompanied by less elaborated flyers that also demonstrated a truly playful attitude to political enunciation: “Say NO to papal reconciliation. The struggle continues” signed by Comandos Herejes (Heretic Commandos) and the Brigada Juan Pablo III (John Paul III Brigade); “We don’t want the Pope; we want sweet potato. Come with your best costume” signed by the magazine Manuela; “Say NO to papal amnesty. March against the Pope. Secular State Now!” signed by the Commission of Repudiation of the Pope in a flyer showing a photomontage of a pregnant John Paul II, among many others. As we can see, the initial intention was to control the affective records to guarantee that such an event did not give in to blasphemy: instead, its proliferation was enabled by creating graphic assemblages that made sexuality a mode of provocation and a form of differential contact with the political juncture. Heresy was not only employed as a language of insubordination to the historical power of Catholicism, but also as a form of profound disidentification from the traditional protest repertoires and the sexual morality instituted as the norm. Operationalising the outrage, the mockery, the grotesque, the sex and the cultural incorrectness, this new generation of young people disarmed the expectations of political agency projected on themselves, prioritising not only creative aspects that involved visual procedures charged with aggression, nervousness, anger and disappointment, but also positioning new horizontal organisational repertoires, in which the absence of authorship and the precarious techniques of multiple reproduction of their expressions were exercised, and which taken together became apologetics of a new way of living the rebellious and insubordinate desires of the radical transformation of the present.

However, all the effort → invested in the successful transversalisation of this demand would be quickly frustrated with a repressive scenario that would almost immediately disarm the call made for that April Friday. Looking at the press of the time, an endless number of headlines can be found that allow us to evaluate the intense military and police deployment that prematurely ended the programmed cultural activities, extending the persecution of the thousands of attendees for hours. With uncertainty as the official number of detainees, the newspapers headlined in sensationalist ways their chronicles of the riots which occurred that evening. In his personal notes, Osvaldo Baigorria (2014) comments that the march against the Pope, who had the aim of reaching Congress, was not even able to start: more than one hundred people were arrested between police charges, smoke bombs, tear gas cannisters and batons. Regarding that episode, he also recounts the testimony of Jorge Gumier Maier, who says that, located in the front lines of the demonstrators, the literary travesti, clown and icon of the independent theatre of that time, Batato Barea himself, initiated a friendly dialogue with the police in order to prevent any conflict between the parties involved, when suddenly a bottle flew from a Ford Falcón car – the kind used by the military to pick up and “disappear” young militants during the dictatorship – in the rear ranks of the march, and it hit the officer right on the head, an act that unleashed the ferocity of the entire repressive apparatus, pushing all the young people to a desperate run towards the peripheral zones of the rallying point.

Launched immediately after that altercation, the editorial of issue no. 11 of the magazine Cerdos & Peces sought to give a detailed account of what happened, but above all it urgently tried to lay down a position against the widespread media stigmatisation that negatively described the difference embodied by the countercultural young protestors, and especially by the anarchists involved in the organisation of the Malvenida al Papa:

[…] The repressive methods tending to a barbarism-based state model become commonplace, not only in the Obelisco, but also it in the rock recitals, in the soccer courts, in the so-called ‘confrontations’ with criminals. That is what is alarming, state violence in a rule of law as the only option to control situations that supposedly tend to disrupt the established order. This is not a model invented by Radicales or Peronistas, but seems to represent the contradictions of a outdated system of national organisation based on organised terrorism […]

As a result of these communications and in line with the documents produced by CRAP at the José Ingenieros Popular Library, in which the same information was reported to call for → solidarity from human rights organisations, a Comisión de Repudio a la Violencia Policial (Commission of Repudiation of Police Violence) was created, and at the same time a course was opened by Juventudes Rebeldes (Rebel Youths), a space that organised the angry energy of the young punks, goths and heavy metal fans, continually harassed by repressive control. The balance of these experiences would not only enable a series of anti-repressive actions that would demand the derogation of police edicts, of background check laws and the request for punishment for the perpetrators of state terrorism, but in a radical way it would pronounce with unshakeable certainty one of the most radical aspirations in the political climate of the post-dictatorial organisation: the total and immediate dismantling of the repressive apparatus.

Against political illusion

Through the fragmentary revision of these countercultural experiences that took place in the so-called “cultural Destape” of the democratic recomposition process during the 1980s in Argentina, I am interested in recovering not only the critical contribution from a set of planned initiatives of collective organisation that, by way of visual devices, performative actions and other graphic artefacts, launched expressive languages that renewed the available repertoires of protest, drawing on the convulsed operativity of negative feelings that combined rejection, irony, resentment, provocation, disenchantment and other twisted form of hope. Moreover, I am interested in recovering the epistemological potential that its awkward difference brings to the history of the sexual and political imaginations of the Global → South. Having been discarded systematically because of their erratic, ephemeral, combustible, reticent or too opaque condition regarding the matrices of normative intelligibility of academic and activist devices, and considered as particularly inconsistent or elusive due to their material fragility and low social circulation, these countercultural experiences propose a type of contact with sexual politics that disorders the linear imperative of history and the neoliberal economies of multicultural representation that have managed to fetishise the cancellation of their practical resonances.

In addition to being thought of as the affective source of a platform of disidentificatory political agency, these collective feelings of disappointment can be considered as an impulse that rejects the desire to → repair the social relations that this particular group of marginalised youth felt were broken[12] in the face of the ongoing repressive sexual morality that inherited its foundations from the military dictatorship, exposing the resounding failure of the democratic promise concerning individual freedoms and their inclusive aspiration. This was a kind of methodical disenchantment with the power in place, which forged emotional platforms of structural antagonism, centred its force of transgression upon bodily freedom as an anti-normative principle – a political presence that strategically intended to resist the alchemical processes of pacific reworking of its distress, turning it into a mode of disengagement,[13] a protest register where such negativity is considered as a language of suspension, that is to say, a strategy capable of blocking the industrialised incorporation of numb subjectivities to the cruel promise of the current social agreement of neoliberalism and its conditions of uncritical reproducibility, opening up imaginative paths for other ways of living.

Putting focus on these political efforts to disengage with the affirmative repertoire of democracy, and give us the opportunity to identify the critical potency of these negative moods as a form of historicity capable of putting together organised experiences around the disidentification with liberal normality. For this reason, disappointment can work as a genre of rejection, one whose transhistorical expression allows us to discern the continuity of an emotional language sustained from an uncomfortable belonging to a “broken” present. This common space created by queer activists, punks, feminists and underground artists is a space of alliance that did not seek to adapt to the therapeutic claim from identity politics or cultural industries, but instead attempted to be a collective form of understanding that engaged critically with the historical present, that drew on the difficulties, lack of cohesion, improbability and ferocious opposition involved in the always fragmentary and insufficient experience of the living.

By unleashing the history of the night and recognising the savage condition of its emotional registers, we may approach a historiographic practice that allows us to describe not only the way colonialism as a form of historical oppression is inscribed within the processes of the creation, access and continuity of the collective memory of alternative sexual communities in the Global South. Moreover, this also enables us to recognise the negative values of factual inaccuracy, → temporal contradiction, chemical dizziness and sexual disorientation proposed in their political imagination as the specific contribution those difficult-to-categorise social subjects have made to the history of antagonistic resistance and the anti-capitalist dreams of the South.

![Subjectivisation 2 [Discussion #3]](/website/var/tmp/image-thumbnails/0/1477/thumb__logo/Discussion-3.png)

![Subjectivisation 2 [Final discussion]](/website/var/tmp/image-thumbnails/0/1478/thumb__logo/Mick-final-discussion.png)