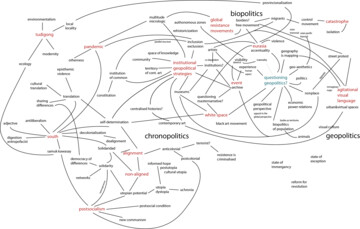

A pandemic refers to an epidemic disease that spreads internationally and indiscriminately, attacking all members of a locality or region. I use the term “pandemic” both at the literal and metaphorical levels in order to understand a number of subjective and geopolitical processes (for instance, the concept of otherness as a disease, and the establishment of an apparent normality that is connected and productive but dysfunctional) to characterise what we call “contemporaneity”. I will try to connect this term with an intention to periodise it, so I may also debate the recent research and future exhibition that Museo Reina Sofia is preparing on the contemporary.

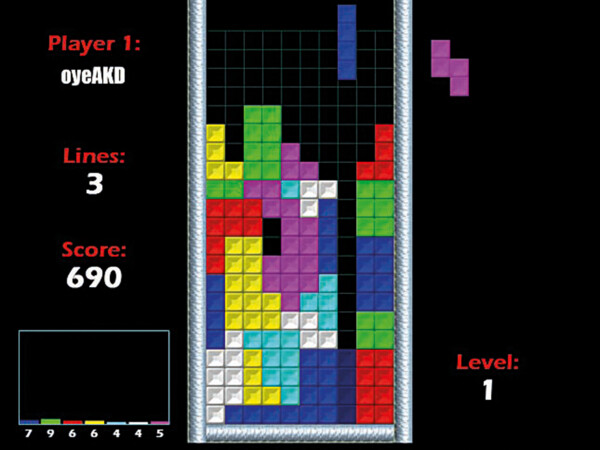

1984 is an anodyne year. Accustomed to a strong and foundational narrative, 1984 appears useless and inconsequential compared with 1989 (the Fall of the Berlin Wall) and 1968 (Paris and the so-called strike of the real). This banality triggers a potential narrative: the ability to reveal a formless and unpredictable → constellation, not yet appropriated by the collective imagination and dominant chronologies of the present time. In 1984, the fear of the Cold War, a condition that largely determines the policy and life during the post-war period, seems to vanish. Reagan delivers his famous radio joke, We begin bombing Russia in five minutes[1] while the uniform and rigid Soviet world is playfully transfigured by Alexey Pajitnov’s Tetris, that video-game of opposing blocks – and not by any changes being developed in the Academy of Sciences of the USSR[2] by the same Alexey Pajitnov, working there in his capacity as a scientist. The Stockholm Conference on disarmament ratifies the fact that bipolar tension seems to vanish like a ghost from the past, while the art system is celebrating, along with various neoconservative theorists[3], the triumph of the global market with the pictorial turn of the neoprimitivisms and trans-avant-gardes.

Figure: Tetris, programmed by Alexey Pajitnov, 1984.

This happy new world is shaken up by the public recognition of HIV. In April 1984 the virus is publicly identified and held responsible for tens of thousands of deaths worldwide. The circulation of the pandemic will transform its own meaning, “the disease of the whole people”, in order to draw new limits of identity, geopolitical and subjective, which will outline a disputed and confronted body. On the one hand, the productive developed and normalised body; on the other hand, the sick, primitive and → deviated body. The pandemic circulation will serve to divide the world into two new axes: the alternate and normal. The origin of the chimpanzee and human contagion in Africa will reinforce the conception of the dark, atavistic desire and the monstrous other, in which the black/colonised subject is the very source of the disease.

The cosmopolitan and universal dimension of the pandemic, as noted by Jean Comaroff[4], will articulate a new concept of power and its action from that moment on. The traditional politics, based on the governance of institutions and individuals, will shift to a biopolitics of production and control of the physical and political body of the population. This new distribution of power will endeavour to demonstrate the relationship between the pandemic and otherness: AIDS will be considered the disease of deviants, the unproductive, and colonised, the so-called 5H (Haitians, haemophiliacs, homosexuals, hookers, and heroin-addicted, whom the Western white body will confront and survive. The concept of biopolitics, proposed by Foucault just a decade before, is key to understanding this international pandemic condition, although today considered insufficient. Achille Mbembe has approached this pandemic geopolitics through a macabre and sadistic version, where biopolitics is replaced by necropolitics. A power that leaves the management of life by the maintenance and distribution of death, assigning dead zones and living deaths, replacing the old dialectic of the colonial and colonised world. If we think of Africa as a territory of exploitation and multinational dispossession regardless of human rights or subsistence, we will approach the living dead version which is posed by the necropower of Mbembe.

AIDS, after all, and its pandemic/geopolitical spread, will determine two conditions: the deviated diseased body and the healthy national body. The pandemic focuses on an abnormal multitude, a collective group of the misguided and unproductive, a community outside of the political production of standardised bodies.

There is a quote which I would like to go back to in order understand this normal and productive body in reaction to the pandemic. Jacques Derrida interpreted the emergence of email as one of the effects of AIDS. A connected and linked multitude, but disembodied, with no mediated contact whatsoever, as an example of the terror of physical infection. A productive and connected but cancelled body.

I’m going back to another event of 1984, that anodyne year in which nothing happens.

Along with the public recognition and detection of HIV, another viral presentation takes place, in terms of global spread. The first personal computer, the Macintosh, is introduced.[5] 1984 won’t be like 1984, is the George Orwell quote in a famous ad for the Macintosh filmed by Ridley Scott, his first job right after the dystopian Blade Runner. In this commercial, a mass with no will rebels against Big Brother, understood to be the then dominant corporation in the office environment (IBM). This new personal computer will be characterised by making easy and simple tasks that were previously fragmented and specialised, eliminating the distinctions among workers, between office and home and, ultimately, between worker and subject. The Macintosh will inaugurate a permanent productivity that keeps you always available, always connected, always producing, in some way it will reshape the domestic sphere according to the time and needs of the financial economy. Quoting Jonathan Crary, it will transform natural time, with its regular cycles and neat separations, into an artificial → continuity of permanent attention.[6] Each computer is a terminal and each terminal is a person who produces in a new global networked crowd, a new body modelled after the absence of borders and times of financial economics.

What is paradoxical is that this transformation opens a supposed sense of freedom and social improvement, when as we know it actually involves an impoverishment of time and an ongoing self-commodification of the subject. A new collective modelled under the conditions of the new factory. A “productive” body affected by an external agent that, in symbiosis, modifies its behaviour on a global scale. Is this not, as another ad for the Mac remarked, “insanely great”? Is this not the same definition of a pandemic with which we began?