The term “contemporary” seems to go against the nature of a glossary, at least as the latter is defined in the standard Spanish dictionary: “a catalogue of obscure or unused words”. By definition, the “contemporary” is the opposite of the “obsolete”, and it is conspicuously used all around our “contemporary” culture as a synonym of brand new. Contemporary has become a “soft” signifier, incessantly claimed in the most diverse fields – from architecture to design, and from fashion to art – one which adheres to an uncritical experience of time. Departing from this approach, here we claim the disruptive potential of the term: anachronism or antagonism versus “the ecstasy of the present”. The contemporary is thus what refuses to relate to its own time, in terms of adjustment or belonging. As such it was described by Agamben, as well as by Mallarmé, for whom there is “a present moment which does not exist”. To feel this → discontinuity of time implies a further → estrangement that allows us to actually keep our situated and contingent positions.

The historical contemporary

“Contemporary” is not just contemporary. The term can be traced back at least to the 17th century, referring to what Rancière would call a new division of the sensible. This shift resulted from the explosion of the focal perspectivism of the Renaissance, due to the need to visually embrace the “expanding” world. New maps and taxonomies to control multiple coexistent “contemporary” differences were created. The rise of scientific positivism and biological racism, both operating within the “new imperialism”, meant the climax of this system in the second half the 19th century. Another crucial “contemporary” turn in the world order came about around the 1930s and the Second World War. The new hegemony of the US devised a more harmonic way to deal with the others, favouring “good neighbourhood policies”. Good examples of this were the exhibitions designed by Edward Steichen for MoMA: The Road to Victory and The → Family of Man, while the Institute of Modern Art of Boston was renamed The Institute of Contemporary Art in 1948.

In the 1980s, the so-called “end of history” came together with the dominant paradigm of multiculturalism. Yet this “contemporary” did not last very long, as it was replaced by a new, violent, and polarised backlash, one marked by war, global terrorism, and financial speculation – superseded by its own crisis. Altermundism and new political movements arose to confront this backlash, in what it was conceived of as a life-and-death struggle.

The contemporary as an artistic and curatorial methodology

At this moment, we perceive an urgent need to face the present by redefining the contemporary. We believe that our → temporality resists being named in affirmative and evolutionary ways. Narratives and poetics that display the disruptive potential of the experience of time are thus required.

Time Bomb (1990) by Pedro G. Romero (Seville, 1964), a “symphonic poem” that traverses Spanish history, works within this logic. This sound piece is an iconoclastic score of events spanning from 1966 to 1990: the terrorist attack on Franco’s successor, or the noisy fireworks during popular celebrations in Valencia. To stop time, kill it, freeze it, hold it back, explode it. This is an archaeological method of inquiring history and confronting tradition. It is a modus operandi that stresses history and rebinds different strata of time, in order to imagine new narratives and meanings.

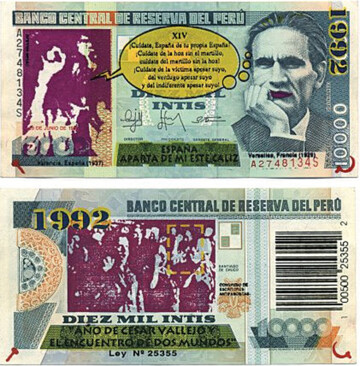

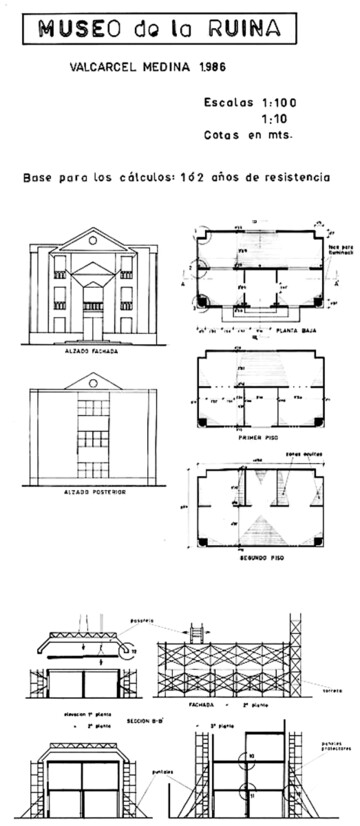

Museo de la ruina (1986), a work by Isidoro Valcárcel Medina (Murcia, 1937), presents an architectural project for a museum that could collapse at any time, given the weakness of its structure. The institution is unable to bear either its own weight or its contents: collections, staff, → archives and so on. Museo de la ruina refers to the impossibility of articulating a master narrative, as well as to the entropy inherent to modern projects. These works were presented as part of Minimal Resistance (2013–2014), an exhibition of items from Reina Sofía’s collection. By recovering a number of artistic practices from the 1980s and 1990s that shaped inter-related narratives of resistance, the project questioned the conventional postmodern reading of “the end of history”.

Isidoro Valcárcel Medina, “Museu de la ruïna (The Museum of the Ruin)”, Quaderns d’arquitectura i urbanisme, no. 263 (Barcelona: Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya, 2011): 81–3.

Minimal Resistance. Between late modernism and globalisation: artistic practices during the 80s and 90s, exhibition view. Curated by Manuel Borja- Villel, Rosario Peiró, Beatriz Herráez, exhibition view, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain, 2013–2014. Photo: Joaquín Cortés / Román Lores. Courtesy of Museo Reina Sofía.

Valcárcel’s proposal of inverting the museum’s dynamics echoes the historical attitude of 19th century artist Melchor María Mercado (Sucre, 1819–1871). Through his album of carnivalesque images of the world “upside-down”, Mercado denounced both the status quo of his own time and the persistence of colonial exploitation, even after Bolivia’s independence. Mercado’s work was shown in The Potosí Principle (2010), as part of a broader “upside-down” curatorial display working to undermine the colonial nature of Western history. This project introduced the idea of an “inverted modernity”, which we could now describe as contemporary.

As a further development of The Potosí Principle’s radical reading of modernity, the project “Losing the Human Form” (2012–2014) stems from the collaboration between Reina Sofía Museum and La Red Conceptualismos del Sur. La Red embodies a new kind of subjectivity, resisting the hegemonic paradigm of the art system both by working collectively and by endorsing alternative ways to relate the past and the present; an attitude that we may also designate as contemporary. For example, instead of a conventional exhibition catalogue, La Red released a glossary of entries, which were intended to work through affinities and contagion. The glossary eventually delineates a fragmentary and committed narrative, in order to ultimately activate and destabilise “the contemporary”.

Losing the Human Form. A Seismic Image of the 1980s in Latin America, exhibition view. Curated by Red Conceptualismos del Sur. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2012–2013. Photo: Joaquín Cortés / Román Lores. Courtesy of Museo Reina Sofía.

Affinities and contagion. A possible glossary of the poeticpolitical practices of the 1980s in Latin America, seminar organised by Red Conceptualismos del Sur and Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain, 2014. Photo: Joaquín Cortés / Román Lores. Courtesy of Museo Reina Sofía.

The urgency to speak from the present leads to a constant negotiation with different and contradictory times. Such a negotiation is necessary to resist the ideological colonisation of the experience of time by the hegemonic “ecstasy of the present”. The open question then is whether, and how, the museum could cope with this intense and shapeless contemporaneity. In other words, how to activate Valcárcel’s poetical proposal from within the museum.