I think of choice on the basis of three instances. One is the multiplication of choices by the → emancipatory movements closely connected to the ideal of freedom from oppression. This is connected to the struggle for the right to have a choice. It is rooted in the desire that drives us to the streets, makes us → raise our fists – as Pablo Martínez puts it – come together in creating the sound pressure to have one’s position heard and listened to. The next is choice as a smokescreen in late capitalism, that uses the imperative of making autonomous choices to conceal the inability of having any impact on mitigating systemic violence. Above all, this choice is not a choice at all, since it only offers things that we don’t need and would never wish to have without consumer-oriented conditioning. The last is the choice that we make with every click on a new webpage, the choice to feed an artificial intelligence (AI) or not, to confirm or reject the insidiously cute “cookie policy” that promises to ensure our ePrivacy. This choice is perhaps more complicated since the argument pro et contra does not fall neatly into our political positions. It is easy for me to say that I am pro-choice concerning social reproduction and that I am against consumer society, but much harder for me to decide if I wish to delegate some of my labour to an AI. A browser makes decisions for me when delegating information on the premises of previous search queries. This automatism might save me from a lot of unnecessary screen time and thus potentially make way for more free time if only I could pull myself from the screen.

Why does it make sense to speak about choice now? I believe that these three instances inform the radicalisation of beliefs today and induce a particular mass hysteria that is quite different from historical cases (such as Nazism or the Cultural Revolution). The current mass hysteria is fragmented but no less detrimental as it produces echo chambers that have just as strong a delusional impact on a person’s sense of reality as the historic examples. It is to be expected that the present delusions will be more difficult to unravel as we cannot expect redemption in the aftermath of their collapse (such as the denazification process of the 1940s or socialism with Chinese characteristics in the 1980s) unless the whole information system is radically restructured.

Choosing pro-choice

From the perspective of politics before social media, the policies that enable conditions supporting multiple choices are the achievements of emancipatory movements that gave voices to the non-representative and fluid subjectivities such as the non-normative body, the female body, the body of colour, the body with a disability, the ungendered body, the old body, or the sick body. The direct actions of the bodies on the streets, exhibiting their → vulnerability but also collective strength, plays out as a multiplication of choices. That is, you are not given only a limited number of choices but the liberty to think and conceive of a choice that did not exist before, as Maja Smrekar has shown with her hybrid family and → mOther(ness). It is not the choice to be a mother or not, but to think of it in a completely different way. The musician Khyam Allami in conversation with Nora Akawi says that it is not the choices you make in the creative → process, but the choice to create a new tool with which you can make choices that did not exist before.[1] These emancipatory projects however → conflictual, violent, and painful they are (for example the pro-choice fight in Poland or the LGBTQA+ struggle in Uganda), belong to the logical political processes that are based on historical precedence and evolve, despite the twists and setbacks, in a rather linear way toward legislative changes that multiply the existing limited choices. Even when a freedom that has already been won is lost – expressed → disappointingly in the viral photo of a woman protesting for the right to abortion with a sign saying “I can’t believe I still have to protest this fucking shit!” – the process nevertheless remains relatively transparent.

Against limitless choices

In her book The Tyranny of Choice, the philosopher Renata Salecl says that we are experiencing acute and paralysing anxiety caused by limitless choices. She pointed out that the idea of choosing whom we want to be and the imperative to “become yourself” have begun to work against us, making us more anxious rather than giving us more freedom. She also points out that the process of choosing is not rational but more often than not an emotional process.[2] For example, human beings don’t always act in their interests even when they know what these are. An irrational decision comes from a feeling of → empathy and is expressed in an act of charity, altruism, and compassion that is not based on self-interest. However, this emotional aspect of choosing becomes twisted when infused by consumerism. Choice brings a sense of overwhelming responsibility into play, and this induces fear of failure, a feeling of guilt, and anxiety that regret will follow if we have made the wrong choice. This process also turns subjects inward to their private life, and prevents them from acting as a community, let alone a politically active one.

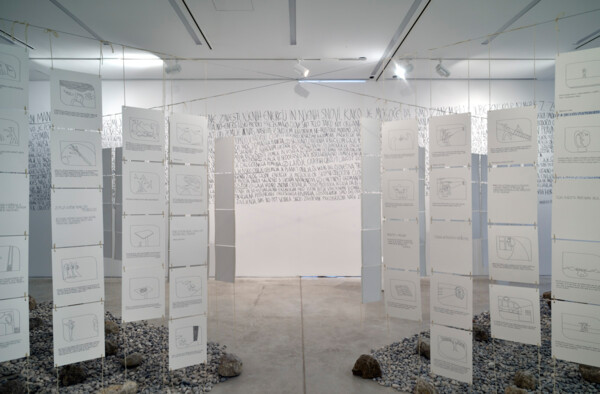

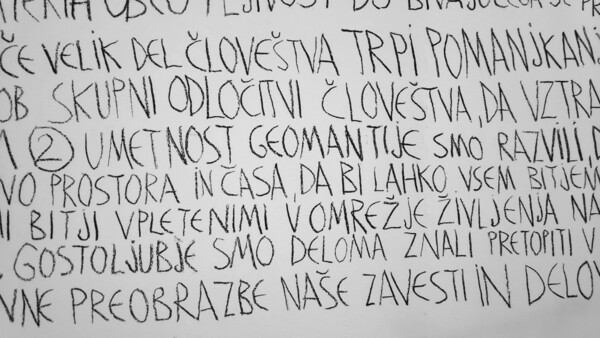

We also cannot neglect that the idea of being allowed to see one’s own life as a series of options and possible transformations is placed in a consumer capitalist backdrop which is essentially classist. For example, the choice of a poor woman to have children is regarded as financially irresponsible. Her choices are never free but conditioned by a socio-political situation. And the way artists who address the notion of choice react is to put into question the choice as an imperative. An early example from Moderna galerija’s collection would be the multiples of OHO Group that proposed reisem, a condition in which they view a different relation between the object and subject in the 1960s at a time when consumer society had just gained momentum. This subject is aware of oneself and objective reality, but takes a completely aesthetic and non-functional relation to the objects. They cease to be tools and begin to have agency. For them, the object has the right to its own autonomy and it has its own right to perform. Later in their work, OHO, particularly Marika and Marko Pogačnik, (Figure 1 amd 2) went even further in proposing a holistic cohabitation not only with objects but with all the things in the world and went on the path of consciously not making choices but letting the natural processes drive the direction that an artistic work takes, which I see as an extremely important method of artistic production at the time of climate change that calls for the ethics of minimal intervention. Their work evolved into a mystical annunciation, speaking about the → Earth as the home for heavenly creatures, the angels and irrational forces that compose the → ecology. Thinking deeply about the agency of inanimate objects sets the scene for a culture that will – sometime soon – find → extractivism unacceptable. As humans we pride ourselves on the ability to create, change and mould things, but the consequence is that we also terraform and extract, plunder and kill with these creative hands. The very young generation today chooses to decommodify. Not in the deep political sense of social reproduction proposed by N’toko (→ decommodification)[3] but their choices are not just superficial. As our mothers chose to be → feminists (and fought for it) their grandchildren now feel that many of Generation Z no longer exist in the patriarchal mindset and are highly sensitive to ecology, fragility, and subjectivisation processes. However, they are involved in the production of new conditions of choosing to a much lesser degree. This static set of abundant choices has produced – on the flip side – a conservative backlash.

Figure 1: Marika and Marko Pogačnik, Geo-cultural Manifesto, 2021, installation view, cardboard, black ink, stones. The Emergency Exit, 3 December 2021 – 11 September 2022, exhibition, curated by Ana Mizerit, Bojana Piškur, Zdenka Badovinac and Igor Španjol, Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova (+MSUM). Photo: Dejan Habicht/Moderna galerija, Ljubljana.

Figure 2: Marika and Marko Pogačnik, Geo-cultural Manifesto, 2021, installation view, cardboard, black ink, stones. The Emergency Exit, 3 December 2021 – 11 September 2022, exhibition, curated by Ana Mizerit, Bojana Piškur, Zdenka Badovinac and Igor Španjol, Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova (+MSUM). Photo: Ida Hiršenfelder.

Choices and normies

The hyper-libidinal and unconscious reign of AI produced by corporate and political interests bombards us and impairs “free” decision-making. It has twisted the achievements of the emancipatory movement in the most shocking way to the so-called “normies”,[4] as Angela Nagle calls the traditional, rational, moderate political subjects from the left political spectrum. She points out examples of identity fluidity that exercise the right to vulnerability proposed by the LGBTQA+ movement. Only that, on microblogging sites this fragility has sometimes shifted from empathetic to pathetic. As she says: “For years, the microblogging site filled up with stories of young people explaining and discussing the entirely socially constructed nature of gender and potentially limitless choice of genders that an individual can identify as or move between.”[5] Gender creation has taken a fantastical turn, and became a subculture on sites like Tumblr. Nagle names a few such as cadensgender – a gender that is easily influenced by music; daimogender – a gender closely related to demons and the supernatural; genderale – a gender that is mainly associated with plants, herbs and liquids.[6] And while we are making kin with other-than-human in an attempt to promote an open and non-restrictive cohabitation, the trouble with such gender fluidities is that they are anything but fluid, they are instead essentialist with the same zealous rigour that one would find in alt-right discussions online. The awareness of intersecting marginalisations and oppressions promoted the discussions about safe spaces, the MeToo movement, and the use of suitable gender pronouns, but at the same time the recognition of → diversity overshadowed economic inequalities. Also, in reverse, the alt-right has in the past ten years adopted the strategies of the emancipatory movements (for example a right-wing politician referencing their freedom of speech when using racist remarks). I still find it baffling how acute the irrationality of some of the online subcultures can be, but what is downright frightening is that the subcultures are no longer hidden in some obscure corner of the “internets”[7] but have emerged into the mainstream political currents, most obviously with the riot in the US capital on January 6th this year.

The problem is the virus. Not the one that dictated our lives in the past year, but the one that has been dictating most of our decisions on information about the world since the coding of the semantic web 2.0. It is the viral process that is inscribed in social media. The virality hailed by the Arab Spring resulted in war and unrest. Any query we make online is informed by our past searches, and this results in an information echo chamber that is responsible for the radicalisation of beliefs all along the political spectrum. It results in tribalism with more or less mystical rites, in that safe feeling of belonging, in the warm accepting embrace of coherence, in the mutual concurrence. But when this soft tribal bubble faces another tribe, then both have to defend themselves with all belligerent force. We would all like to have the feeling of control over the choices we are making and a sense of autonomy. Unfortunately, the way the code is written is informed by the use of manipulative consumer marketing strategies that spilled from the economic sphere to the sphere of ideology. Vladan Joler, in a text on digital data mining that he calls “→ new extractivism”, reveals that the bodies of each and every one of us are being colonised. We, as “dividuals”, are the final products being sold to advertisers. In this world, the economy is no longer limited to the trade in goods and services, rather it has expanded to include the economy of the mind, such as the attention economy, the emotion economy, or the economy of beliefs. Joler’s allegorical map is written in the manner of speculative fiction, yet it is anything but a fantasy. It is a realistic depiction of the echo chambers that produce radicalisation of the mind.

What is to be done is to decolonise AI not only in the sense of reprogramming the algorithmic biases based on racial discrimination and the global digital-divide, but also to propose another non-viral form of information rhizomatic structures that do not single out preferences according to habits. The way to do this now is not what the traditional media is trying to do to reference truth and correct controlled information, but on the contrary to introduce in the code a lot more randomness and unpredictability that would offer a substantially more open and versatile information stream, such as the Mastodon social network of independent, federated servers, or the return to the old-new chatrooms on Discord.

![Subjectivisation 2 [Discussion #3]](/website/var/tmp/image-thumbnails/0/1477/thumb__logo/Discussion-3.png)

![Subjectivisation 2 [Final discussion]](/website/var/tmp/image-thumbnails/0/1478/thumb__logo/Mick-final-discussion.png)