The apparent self-evidence notwithstanding, two reasons led me to hesitate before proposing the term “South”.

The first has to do with the current, ongoing plight of migrants and refugees. Like all of us, I am concerned with what is taking place right now – which is entirely the outcome of “geopolitics”, and, as has been pointed out, changes by the hour. How can we remain indifferent to the images that we have been seeing in the media over the past week[1], mentioned here on numerous occasions? There is, however, one particular kind of image that has started to “work on” me, in the way images – like ideas – are able to “work on” us. The images of people walking through landscapes, along railway lines, through city streets or alongside fields. People moving and moving, changing directions as required, but always moving. I felt we needed to discuss this incessant movement, its meanings, reasons, and consequences.

The second reason is that I was not sure – indeed, I’m still not – whether or not the term “South” can be “operative” in this framework. As I see it, the constitution of a glossary seeks to have terms that can operate in a performative or material way in a given field. Meaning that they should be able to act in this field. Is the term “South” operative here? Could it be? And how?

In spite of – or along with – these hesitations, I have chosen to present the term because I feel it merits discussion. Over the past two decades, the term “South” has been the object of many politically motivated appropriations and re-conceptualisations. Historically, the South was postulated in opposition to the North, on the basis of irreconcilably divided modes of production and modes of being. In this conception, the South was shrouded in an aura of romanticism: the South was a “given condition”. In this way, geography appeared, at the same time, as the element that at once conditioned the division and provided its explanation. It was both the cause and consequence of this binary division. We can retrace the history of this terminological and conceptual opposition back to the very foundations of Europe and the abundant literature that explains the “differences” between Germanic and Greek peoples and folklore – an opposition, which, as I scarcely need mention, has more recently been updated into other terms. In any case, both North and South share this conception, endlessly producing and then reproducing shuttered and fixed identities, univocal narratives, and all-encompassing economies. In a way, this complex – albeit simplifying – structure is not only political but biopolitical.

The South: Between geographical and cosmic definitions

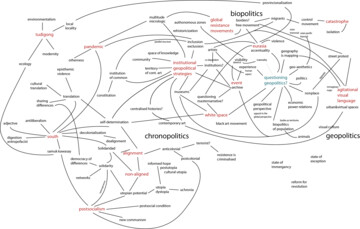

As we know, North and South are determined by a conceptual line, the Equator, which divides the world into two halves. A number of monuments have been built along this as markers of an inexistent line. We find, for instance, a monument in Pontianak (Indonesia), another in Macapá (Brazil) and, of course, yet another in the country actually known as Ecuador. There the marker is situated in the suburbs of the capital city, Quito. Ecuadorians claim their country is the only place on Earth where the line bisects a major city. A monument marks the alleged spot, situated in a place aptly called La mitad del mundo (“The Middle of the World”). La mitad del mundo is a kind of theme park, where visitors can stand with one leg in the South and the other in the North, undertaking such experiments as observing how an egg stands alone on its axis without falling over, due to the way gravity functions along the equator.

Figure 1: Monument at La mitad del mundo and the site where GPS measurements show “The Middle of the World” in Quito. Photo by Mabel Tapia.

Figure 1: Monument at La mitad del mundo and the site where GPS measurements show “The Middle of the World” in Quito. Photo by Mabel Tapia.

Built between 1979 and 1982, each side of the monument at La mitad del mundo faces a different cardinal point of the compass. Ironically, a problem arose when GPS measurements became widely available, because they seemed to establish that the equator was not actually at La mitad del mundo, but rather 200 metres further south. So now there’s another marker. This marker is also in a theme park, though the theme is slightly different, being mostly dedicated to indigenous life in the region, but also includes a sign proclaiming 00.00.00 degrees of latitude “according to GPS measurements”. The fact remains, however, that different GPS devices show different measurements. In short, we don’t really know where the equator is, which means that we don’t know where the South begins or ends. (Figure 1)

Let’s leave the Earth and move to another conceptual field – in the sky. As we all know, the celestial sphere is a scientific construction devised to investigate the space around the Earth. In the celestial sphere, we find a → constellation known as la Cruz del Sur – the Southern Cross – or sometimes simply The Cross. This constellation provides the points for tracing a kind of cross and has been the object of many interpretations over time and in different cultures. According to the Incas, it as a kind of ladder or bridge connecting three worlds: the kay pacha (the terrestrial world), the hanan pacha (the world of the gods) and the uku pacha (the world of the dead). At any rate, the longest line of this cross points due south and is supposed to guide navigators on their southerly journeys. The problem, however, is that one only sees this constellation if one is already in the south. It cannot be seen from the north.

Even if the terrestrial landscape and cosmic skyscape can help us to conceive of the South, they provide no clues as to how to make sense of it or to account for the “given condition”.

Dislocating the given condition

We find any number of linguistic operations that work to dislocate the given condition.

Here are two examples:

“El Sur también existe”[2]

A first operation is a claim-laying or reactive one, resulting from the binary struggle within the “North-South paradigm”. Many expressions of popular culture attest to the necessity of establishing the South as a condition to be upheld in the public sphere. Take the famous 1943 drawing by the Uruguayan artist Joaquin Torres García, America invertida (usually translated as America Upside Down). In his text Universalismo Constructivo [Constructive Universalism], Torres García states in no uncertain terms the reasons behind the name of the Ecuela del Sur [School of the South], which he had founded, saying: “For us, there should be no North, except by way of opposition to our South. Thus, we have now turned the map upside down, giving us a fair idea of our position, and not as the rest of the world would have it.”[3] This operation inverts the opposition, but still keeps it in place. It does not break with the macro-structure that enabled the opposition in the first place. Although the artist is clearly proposing a way to resist the given condition, the operation itself remains active as an oppositional paradigm.

“El sur es lo que está después, lo que está por venir.”

The well-known 1988 film Sur [South], directed by Fernando “Pino” Solanas, opens with a famous tango of the same name, in which we hear one of the characters paraphrasing the lyrics, intoning: “El sur es lo que está después, lo que está por venir.” [“The south is that which is still ahead, that which is yet to come.”] This can summarise the definition of the South as a direction (as with the constellation la Cruz del Sur, or Southern Cross), or an unfinished project, a future horizon, or kind of utopia. In a way, it points beyond a given condition, but only at the cost of evading the problem as such.

Reshaping what “South” means

In its Founding Declaration, the Red Conceptualismos del Sur (Southern Conceptualisms Network) adopts “a strategic use of the term ‘South’”. It is used with the purpose of intervening in the geopolitical segmentation of Latin America, within the current hemispheric conjuncture. The geopolitical condition of the “South” is not used as a metonym for the geography of Latin America, but as a discursive tool for dismantling “centrality” and reversing the epistemic “marginality” through which global “conceptualisms” have been historicised. Through the strategic and geopolitical use of the term “South”, the Network seeks to ensure that the Latin-American stance is informed not by a reclamation of some regional cultural identity, but, rather, that it allows the rethinking and revision of the strict dichotomies that divide centre and periphery, canon and counter-canon, First and Third Worlds, Western and non-Western.

The operation consists in taking over the “given condition” and reshaping its content. The South must thus no longer be confused with a geographic position. Indeed, it is not – or ought not to be – geolocated at all. It becomes – with all its possibilities and limitations – a collective and politically active “site of enunciation”.

The South can also be exclusive

The artist Runo Lagomarsino (born in Denmark to Argentinean parents, living in Brazil) presented a paradoxical piece in the exhibition Canibalia held in Paris at the Kadist Foundation space. A pile of posters lay in the exhibition space, all bearing the following sentence, printed against a sky-blue background: “If you don’t know where the South is, it’s because you are from the North.”[4] In other words, understanding is reserved to those who belong to the South... regardless of what the South actually means. This is all the trickier since, as I have mentioned, it is not clear where exactly the South lies. This non-dialectical statement has two implications: access to comprehension (of the South) is ensured by a link of belonging, which, apparently, relies on some form of exclusion.

The South as a mode of inquiry

In a very different way, the Portuguese sociologist, Boaventura de Sousa Santos, has deployed the notion of the South in order to explore “epistemological and theoretical alternatives that may enable us to get beyond the blindness in which the Western-centrist critical tradition seems to be locked down”. In his work Epistemologies of the South[5], Santos asserts that these southern epistemologies are based on an “ecology of knowledge” and “intercultural → translation”. Arguing that we are in a profound crisis of Eurocentric theory, the sociologist explains the necessity of these → alternate outlooks by describing our social context through the analysis of four specific domains. One: we live in a period of powerful questions and weak answers. Two: our era is characterised by huge contradictions, specifically between the urgent need for change and the civilisational transformations this would require. Three: we suffer from what he refers to as the “loss of nouns”. For Santos, critical theory has forfeited “all the nouns, keeping only the adjectives”. If in the past, conventional theory talked about democracy, today it talks about → radical democracy. (A similar phenomenon can be observed in art with what I have elsewhere called a “process of adjectivisation of art”. A displacement or kind of “deterritorialisation of art” has occurred over the last decades and is palpable in speech itself. We talk less about works of art, or production, than about artistic practice. In this sense, art has given itself the potential to be a tool for social movements.)[6] Four: Boaventura de Sousa Santos’ last domain of analysis is the ghostly relationship between theory and practice. According to Santos, recent decades have seen progressive change come from social groups utterly invisible to the tradition of European critical theory.

In this context, the South names the necessity and possibility of exploring new methodologies and epistemologies. In this case, the South does not necessarily refer to a geographical position which determines a way of being; on the contrary, it names other possible ways of doing.

Beyond the South: Other cartographies

Figure 2: Participants and Iconoclasistas, Belo Horizonte, a collective workshop of cartographies. Photo courtesy by Iconoclasistas.

From this perspective, it is no doubt time to envisage and develop new cartographies – such as those proposed, amongst others, by the Iconoclasistas collective in Argentina. This group engages in producing collective maps (Figure 2), which break up given cartographical and, more importantly, geographical notions, enabling us to understand space as a geo-bio-political territory.

New cartographies are being produced right now, as we speak, sketched out by the paths of refugees and migrants as they move. These living maps challenge traditional notions of North-South, even as they propose a new cartographical imaginary.