The term I would like to propose for the Glossary of Common Knowledge is “lobbying”. This term has two main meanings. First, it can denote a group of people or representatives of an interest group working together to influence government decisions on specific issues. The second meaning is spatial; it refers to a foyer or an anteroom, for example, the one in the British Parliament, where members assemble to vote during a division. My proposal embraces these two meanings as a starting point to explore how lobbying, in the cultural sphere, gives form to an alternative institutionality in the ongoing museum crisis in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Let me begin by describing an event in Sarajevo, which happened on 4 October 2012. Dozens of protesters, students, and citizens of Sarajevo were gathered in front of the entrance of the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, witnessing what has already become a historical event: the doors of the museum were to be locked and nailed with wooden panels, as if a tornado were on the horizon. In handwritten red letters, “Zatvoreno” and “Closed” were inscribed on the panels, making clear that the Bosnian National Museum was being closed to the public for the first time in its 125 years of existence. The cultural activists had been mobilised to make this desperate attempt to save cultural heritage in Bosnia-Herzegovina in response to one of the distant but still pertinent effects of the political framework sealed with the Dayton Peace Agreement from 1995 that ended the 1990s war. That agreement displaced ethnic conflict from the sphere of armed forces to the sphere of culture, where new battles took place over history and memory. Six other state-level institutions in Sarajevo, including the National Art Gallery and the National and University Library, were also suffering from an unresolved legal status and lack of funding, and, it was rumoured, were also on the verge of shutting their doors to the public.

This cultural crisis, which is easy to minimise even as it works to lobotomise whole cultures, caught the attention of artists, academics, students, cultural workers, and activists from Bosnia-Herzegovina and beyond. Their lobbying activities shed light on both the museum crisis and the unprecedented → solidarity [→ solidarity → solidarity] that it unleashed among various groups across ethnic and disciplinary borders, culminating in a multiannual collective effort to save cultural heritage in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) through new forms of self-organised cultural production. The examples of lobbying that I would like to present for the Glossary work through an artistic lens to address the causes of Bosnia’s institutional crisis within the context of the socio-political transformation processes that have traversed and remade → Postsocialist Eastern Europe.

Among the first to act was one by the Bosnian conceptual artist Damir Nikšić. In 2011, Nikšić occupied the National Gallery of BiH following an announcement that the gallery would be shut down. In his artistic response, Nikšić proclaimed himself the “Mini Star of Culture”, taking on a position as, literally, the country’s only Minister of Culture. The artist occupied the National Gallery for eighty-three days, calling for a “gathering of intellectuals, artists and experts”. His intention was to lobby for a new Constitution of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Republic, critiquing the present Constitution as “racist, segregationist and found illegal by The European Court of Human Rights”[1]. To organise this gathering, Nikšić invited Sarajevo’s prominent intellectuals and cultural auteurs for conversations held in the National Gallery, which were recorded and publicised daily via the artist’s YouTube channel, throughout the entire period of the intervention. This occupation was aimed at calling attention to the fact that BiH lacks a state-level Ministry of Culture to represent all ethnic groups in the country. In this sense, Nikšić’s action linked the cultural crisis of BiH directly to the disintegration of Yugoslavia and its political consequences of the past two decades, pointing at not only the absence of a state-level cultural ministry but also the lack of a shared perspective on the country’s history, identity, and sovereignty.

A year later, when the National Museum in Sarajevo shut down in 2012, a series of protests and spontaneous actions were organised by various groups in public spaces. These included the Anti-Dayton activist group and numerous protests from university and high school students. The Third Gymnasium and the First Bosniak Gymnasium, for example, even presented the Federal Ministry with an action plan to rescue the National Museum. Besides the local lobbying activities, a number of both regional and international cultural institutions organised various campaigns and actions involving major transnational museum networks, such as the ICOM and CIMAM. The Museum for Contemporary Art Metelkova and the Moderna galerija Ljubljana have been continuously documenting and archiving accounts of these cultural protests over the years.

Inspired by all of these actions, I wanted to address the cultural and political crisis in BiH through my access to an international network in order to connect the realms of art, academia, and museums. In January 2013, together with my colleague, Maximilian Hartmuth, an art historian from the University of Vienna, I launched the CULTURESHUTDOWN platform. We formed a focused editorial board group and a wide international network gathering more than 50 international artists, scholars, and experts from various fields, who at that point had already been lobbying against this crisis from the perspective of their respective disciplines.

Figure 1: Azra Akšamija and Maximilian Hartmuth, CULTURESHUTDOWN, artistic platform, 2013, with sculpture by Duba Sambolec, "Soc. realizem", mixed media, 197 x 71 x 46.5 cm, 1976, in 20th Century. Continuities and Raptures: A selection of works from the national collection of Moderna galerija, Moderna galerija, Ljubljana. Courtesy of the artist.

CULTURESHUTDOWN was set up as an international civic platform that operates through a website and connects cultural activists across geographic and disciplinary borders. The platform’s mission is to host and give visibility to various individual responses, and it attempts to resolve the acute crisis of BiH’s cultural institutions. Over time, CULTURESHUTDOWN has grown in scope and depth into a global platform connecting cultural producers who voluntarily lobby through their work and production of multidisciplinary projects. Our shared objective is to envision a better future for Bosnia’s war-torn society and to reimagine, through a cultural dialogue, new modes of coexistence in the region. (Figure 1)

Reaching this objective necessitated a thorough investigation of the causes behind the museum crisis, looking behind the established understanding that the budgetary problems were the source of the institutional collapse. To that end, I hired a local investigator, journalist Selma Gičević, to interview the representatives of all affected institutions, map the status quo, and collect the institutions’ individual perspectives on the crisis. After the survey was completed, the CULTURESHUTDOWN editorial board wrote a report that unified all of the museums’ individual problems into a joint perspective, showing how all of them are affected by a common concern. Collecting all voices into one was very important, because the affected institutions had previously not been working as a group to address the problems that impacted them all.

This initial survey led us to a key discovery: the cultural institutions in BiH had no legal status as state-level institutions. While all of them exist physically – they were established during the previous regime as regional institutions of Yugoslavia’s Federal Republic of BiH – none of these institutions were legally recognised as state-level institutions when BiH became an independent state and established its constitution through the Dayton Peace Agreement in 1995. That is to say, the state of BiH never proclaimed, “Yes, this is my state museum, or no, it’s not my museum” – the museums do not exist on paper. This problem of lacking a legal status affects all other problems because no one feels responsible for securing sustainable financing for these institutions, and there is also the problem of responsibility over leadership: Who will appoint the next museum director after the current one retires?

With this insight, the first agenda for the CULTURESHUTDOWN platform was to raise awareness about this specific underlying cause of the museum crisis by promoting the perspective that the cause of the problem is not just the lack of budget but also the unresolved political conflict. Another important goal of this first agenda was to promote an understanding of why it is important to have museums at all, and to recognise that they serve as keepers of memory, which the nationalist extremists sought to erase in the recent war. In a society recovering from the consequences of war, museums and → archives represent a contested sphere – they are in crisis precisely because they preserve this memory and material → evidence of existence and coexistence that was targeted during the war.

We could see BiH as a mini model of Europe – a place where different cultures and civilisations have met and lived together for centuries. This coexistence was not always peaceful, but the cross-cultural exchange and fertilisation were quite dynamic throughout history, which is very much evident in the region’s rich cultural heritage. In almost every village and city in BiH, major religious buildings of the Muslim, Catholic, Orthodox Christian, and Jewish faiths are standing literally side by side. This cultural heritage represents material evidence of the transcultural détente put into practice over generations in BiH, and, because of this, nationalist extremists specifically targeted it during the 1992–1995 war. Mosques, churches, libraries, archives, and museums were targeted deliberately, and this destruction reached a wide scale. For example, over 70% of the Islamic cultural heritage in BiH has been destroyed or significantly damaged. In 1992, the National Library of BiH in Sarajevo was targeted with incendiary grenades. When Sarajevo’s citizens built human chains to try to rescue books from burning, they were shot by snipers who were making sure that firefighting operations could not be executed. András Riedlmayer, director of the Aga Khan Documentation Center at Harvard University and an editorial board member of CULTURESHUTDOWN has called this destruction “the largest single incident of book burning in modern history”.

The systematic destruction during the war in BiH represents, in fact, a process of territorial conquest and demographic rearrangement through ethnic cleansing and genocide, as evidenced in the demographic maps of the country from before and after the 1990s war. The ethnic → constellation before the war shows the distribution of all ethnic groups across the entire country, while after the war the three main ethnic groups were separated into three homogenised ethnic territories. This new and brutally constructed demographic landscape was then confirmed through the territorial arrangements of the Dayton Peace Agreement, which split the country into two political entities, the Serb Republic and the Federation of BiH. Constructed through genocidal actions, this internal political division is considered unacceptable by many and has led to a post-war continuation of the conflict within the cultural sphere. Today, ongoing battles are taking place over history and memory through the political instrumentalisation of cultural heritage. The museum crisis in BiH exemplifies this ongoing struggle. In one part of the country, you have people saying, “Well, this is not our history and not our national museum. We have our own history and we have our own museum.” Another part of the country is saying, “We need a shared cultural ministry and a shared national museum” to counter the effects of the ethnic cleansing and genocide.

The second agenda for the CULTURESHUTDOWN platform was to promote an understanding of museums as symbols and instruments for reinstituting the idea of the BiH as a multi-ethnic state. To that end, we were seeking ways in which people in BiH can reclaim their shared history and create a new cultural capital for the shared state to counter the violence of war and competing nationalisms of today. That necessitated making the case for cultural preservation and for the museum as an instrument for state building and peace. With this agenda in mind, I initiated a campaign called Museum Solidarity Day. I wrote to 2,000 directors of galleries and museums and hired students to help me find these contacts. Participants were invited to sign up on our website, upon which I sent them a strip of our yellow barricade tape with the CULTURESHUTDOWN logo. Participants were invited to cross out one artefact in their collection for one day using this tape, to take a picture of this action, and then upload the pictures online. This was an “insane” logistical action. To get the campaign started, we had a lot of support from colleagues in Ljubljana; Zdenka Badovinac was especially instrumental in promoting this action through CIMAM, of which she was the president at the time.

Figure 2: Azra Akšamija and Maximilian Hartmuth, CULTURESHUTDOWN, artistic platform, 2013, from Museum of Pharmacy History, Faculty of Pharmacy, Belgrade, Serbia.

After a couple of institutions participated, the action went viral and global, reaching 390 institutions in 40 countries on five continents, with everyone using the same visual trope of crossed-out artefacts. The participation included major national museums, history museums, contemporary art museums, a number of Jewish and Holocaust museums, art galleries, and universities. Some participants, who did not sign up in time to receive the tape, improvised their participation by making their own tape. All major cultural institutions in Ljubljana participated and supported this action. A very significant outcome was that many institutions from BiH, Croatia, and especially Serbia, supported this campaign, sending a political signal to institutions in the Serb Republic of BiH, which had boycotted the call. The → solidarity [→ solidarity → solidarity] actions in Serbia proper represented a powerful counterstatement to Serbian nationalists in BiH. (Figure 2)

Figure 3: Azra Akšamija, Museum Solidarity Lobby, Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova, +MSUM, Ljubljana, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

The presentation of all the collected photos achieved a major media presence in BiH though national TV and radio channels, paying tribute to museum workers who were keeping these institutions alive for 20 years with minimal and irregular salaries. Showing some respect to the museum workers was very important, because they were previously publicly perceived as unprofessional and not able to gather the funds for the museums. Subsequently, I used these crowd-sourced images to create an exhibition of CULTURESHUTDOWN banners on the façades of the affected museums, where they were displayed for more than a year. (Figure 3)

Despite these moving and global acts of solidarity, we should not forget that the establishment of the National Museum in BiH was a product of a colonial project. The museum was founded in 1888 by the Austro-Hungarian Empire as an institutional form of identity creation for the region, which up to that point had been part of the Ottoman Empire. The museum’s collection has never been significantly revised after the 1990s war. Hence, the third agenda for our lobbying activity was to force a discussion about the content of the museums. In this context, I developed a project called Future Heritage Collection, which aimed to relocate the discussion about cultural preservation from the realm of closed-door → bureaucracies and academia into the public realm and ask the following questions of citizens of BiH: “What is to be preserved for the future? If your museum is closed, could you take on the responsibility to be a curator of your heritage? What is → missing in these collections, and what would you store in these museums?”

Figure 4: Azra Akšamija, Future Heritage Collection, postcards, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

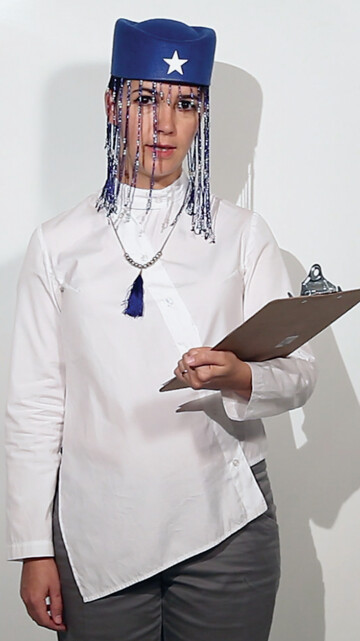

For this project, I staged myself as an archaeologist from the future who is sending a video message to citizens of the world and asking ten questions about heritage and preservation. In one such question, while suggesting that aliens have come in contact with the inhabitants of Earth, the archaeologist from the future asks citizens of the world to propose one artefact of cultural heritage that would represent the entire world. In another question, the archaeologist from the future asks whether access to cultural heritage that is currently inaccessible should be considered a form of human right. Another question addresses expertise over preservation, as exemplified by the instance of the “restoration gone wrong” of the Ecce Homo fresco in the Sanctuary of Mercy church in Borja, Spain. A local artist, Cecilia Giménez, had restored the face of Jesus, according to her own standards and was subsequently mocked and laughed at by the entire world. The archaeologist from the future, however, puts the judgment over her restorative → interventions in question, claiming that she has become a very famous artist in the twenty-second century because of her preservationist masterpiece. (Figure 4)

Figure 5: Azra Akšamija, Future Heritage Collection, postcards, 2013. Courtesy of the artist.

The call for participation in establishing the Future Heritage Collection in Sarajevo was distributed through various media channels. Working with the <rotor> Center for Contemporary Art in Graz and local artists and curators, I arranged a public discussion about the museums’ collections, which took place within the international theatre festival MESS. We invited local cultural actors and NGOs, such as Akcija, to discuss the contents of the BiH museums, including whether they had an opportunity to revise them. A temporary office of the Future Heritage Collection was set up at the JAVA gallery in the centre of Sarajevo, where citizens were invited to bring artefacts of cultural heritage that represent BiH’s shared history. Many beautiful examples were brought in, such as a sample of embroidered textile that appears to be a typical Islamic cultural artefact but was brought by a Serbian woman who explained that this cloth was her wedding band, part of a Serbian wedding tradition in BiH. All the collected artefacts were then photographed, displayed, and catalogued during the show, allowing citizens to follow, in real time, the establishment of the collection in the making. Images of the artefacts were transformed into postcards on which participants were able to add their own stories. The postcards were given to the Centre for Cultural Heritage, International Forum Bosnia, for public distribution. (Figure 5)

While our lobbying activities have been informed by previous actions of BiH citizens, students, artists, and cultural workers, they have also informed the establishment of subsequent lobbying undertakings in the region. One of the succeeding actions in Sarajevo included the wonderful project conducted by the NGO Akcija. The Museum Guards (Čuvari muzeja) project acknowledged the hard work of the museum workers over the years through photographic essays and a public exhibition in the museum. Another powerful campaign – I am the Museum (Ja sam muzej) – involved inviting prominent BiH citizens (politicians, religious leaders, high school students, different independent organisations) to spend a night in the museum as its guards. This major campaign involved more than 3,000 people as museum guards, making the citizens responsible for preserving their own history and institutions. Ultimately, Akcija’s lobbying activities have continued the spirit of CULTURESHUTDOWN’s lobbying into the local realm, having an impact on cultural policy and, finally, to the reopening of the National Museum. The questions of a countrywide cultural ministry and the legal definition of the museums, however, still remain unanswered.

The culminating process of cultural lobbying has led to some successes on both an international and regional scale, and it continues through discursive projects and exhibitions, such as the Inside Out – Not So White Cube exhibition curated by Alenka Gregorič and Suzana Milevska at the City Art Gallery Ljubljana in 2015, which then travelled to the Contemporary Art Museum in Belgrade for the Upside Down – Hosting the Critique exhibition in 2016. All these forms of cultural lobbying in the region are collectively interrogating the Institutional Critique against regional politics and parameters of artistic production and exploring new potentials for the museums to catalyse new understandings of citizenship, cultural preservation, and artistic practice. The notion of lobbying, notably for the museum, introduces a unique dimension in the context of Institutional Critique, acknowledging the museum’s institutional power structures in instrumentality, colonialist, and nationalist projects, while simultaneously, and perhaps paradoxically, creating an understanding of the museum as a site in which we can begin to reclaim the lost notion of public virtue. Museum Solidarity Lobby is a phenomenon of other institutionality, that is, a vehicle to reclaim things such as the solidarity, cross-cultural empathy, collective memory of coexistence, and integrity of public institutions, as well as an opportunity for cultural renewal in conflicted societies.