Museo Situado: Pepa’s Dream[1]

Let me start by telling you a dream: the dream of Pepa Torres, an active member of Museo Situado, as narrated by herself to the assembly in one of our weekly Zoom meetings during the quarantine.

In her dream, she was evicted from her home by the police in the middle of the night together with many other neighbours, something which was increasingly common during the violent process of gentrification of Lavapiés. Unexpectedly, Ana Longoni, director of the Public Activities Department of Reina Sofía, but also a frequent participant in anti-eviction demonstrations, led the group to a secret entrance in the walls of the nearby Museum to provide them with shelter.

The sense of → vulnerability behind Pepa’s dream was justified. Even if evictions had been temporarily suspended, the COVID-19 confinement made the fragile situation of many neighbours of Lavapiés critical. Migrants, refugees, precarious workers and the elderly, being isolated and without easy access to public aid, would feel helpless and unprotected.

While the world was collapsing outside, the vaulted ceilings of the Museum covered a safe space, a kind of Noah’s Ark in which “all species” were welcome. This was not all. Once inside, as Pepa recalled, a party started, dancing together as they used to in the picnics organised by the assembly in the inner courtyard of Reina Sofía.

Her dream probably contains personal and social projections about the benign nature of the museum and the salvific power of art, but I feel that it also → translated the more “subversive” intentions of the participants of Museo Situado. Most members of the assembly, I should say, disliked the word situado, chosen by the public activities department to refer to the explicitly local and politically engaged character of the project. For them, who may have not read Donna Haraway, it sounded very much as sitiado: under siege.

The military connotations of this homophony, which traditional activist “militants” may have celebrated, had nothing to do with the → feminist intentions of our group, as the activist Rafaela Pimentel reminded us in one of the last meetings of our assembly. They actually preferred the term agujereado: “pierced”, which takes us back to the breach in the walls through which Lavapiés neighbours penetrated the Museum in Pepa’s dream. Agujerear el Reina (Piercing the Reina) is the name of our WhatsApp group.

This image refers to the Museum as a castle, the guarded gates of which were designed to keep “people like them” outside. It also implicitly identifies the group as a bunch of “outcasts” who, although they may not intend to “take over the castle after a siege”. In military terms, they are aiming to more subtly, but steadily, perforate it like rodents, in order to enter and unlock the institution from within. Perforating, unlike conquering, works on the structure of the building, making it porous, soft, and exposed to external influences, transforming the relationship between the inside and outside. It involves both a danger, since it erodes the solidity of the fortress, and a new life, since the holes permit breathing and the circulation of flows which may, otherwise, become a perilous wave, or finally move to other watersheds.

Piercing requires conspirators inside. In fact, the proportion of the Museum staff participating in the assembly increased rapidly during the short life of the project. The fact that many of them were precarious workers or unpaid interns, and some were already engaged in different forms of activism, became suddenly visible, providing a different perception of what the institution is actually made of: people with whom to share needs, demands and projects. This perception, which worked both ways, made it possible that the same walls that protect the castle could also allocate an assembly, keep a garden, or provide shelter in difficult times.

During the quarantine, meetings become more frequent, two or three a month, and the related actions more agile and effective, as if all the participants knew how much it was at stake and the urgency to deliver a response. Museo Situado rapidly took its place within the tide of → solidarity which was rising in the neighbourhood. In truth, it could not have been otherwise, since some of its most active members like Nines, Pepa, Rafaela or Elahi were key elements in the support networks of Lavapiés and beyond. Some others, being part of the Museum as staff or interns, such as Mariona, Brenda, Carolina or Sara, worked hand in hand with them in setting up ingenious devices of enunciation and communication – campaigns, seminars, and workshops, which took the Museum as a (virtual) place and platform.

The hole in the Museum walls became a loudspeaker through which to project the voices of many who had been structurally absent and found there a temporary platform in this exceptional season. Voces situadas (situated voices), a series of open seminars launched by the Museum to convey the public debate on urgent social issues, provided the format for this. Let me list some of the voces situadas organised by the assembly before, during and → after the quarantine:

Voces situadas 10: Debt. Plural feminine (26 November 2019)

Voces situadas 11: The Value of Strawberries: Slaves of the 21st century (5 March 2020)

Voces situadas 12: Who Takes → care (→ care) of Carers: Capitalism, reproduction and quarantine (27 May 2020)

Voces situadas 13: Surviving Together: Community organisation in times of pandemic (24 June 2020)

Voces situadas 14: The Virus within the European Fortress (29 July 2020)

Voces situadas 15: We are all old, we are all mortal (2 September 2020)

The feminist and internationalist profile of these activities reveals that the situated nature of the project was not so much about interacting with the locals, as could be expected from a museum community group. It was about the political right to be and to speak from the Museum. During the exceptional time of the pandemic, Museo Situado made the membrane of the institution vibrate differently. Something happened in the institution when new bodies got present (even if online), took a stand and spoke with an accent, a skin, a sexuality and a social class which were previously excluded, and when that act of speech mattered and convened a community of a new kind.

This involved negotiations with the solid skeleton of the institution which were not necessarily easy. This was the case after the proposal of some members of Museo Situado to use the walls of Reina Sofía to hang banners of the campaigns promoted by the assembly to suspend housing rents, to legalise migrants, to demand translators in health services, or to claim labour rights for domestic workers. This would imply a public exposure that the Museum may not be in a position to have.

But what do they want from an art museum?

In Museo Situado there is a faith in the powers of both the institution and art which can be rarely found among members of the “art world” or its usual analysts, like myself. The members of the assembly do not just intend to use the walls and resources of the institution strategically in order to convey their demands for social justice. They firmly believe that the mission of the Museum is to do so. They fight for a world in which the Museum is on the side of the common good, in which it does what has to be done. This is a very powerful demand that the art institution should not dismiss in a period of severe crisis, a time in which the worst may be still to come.

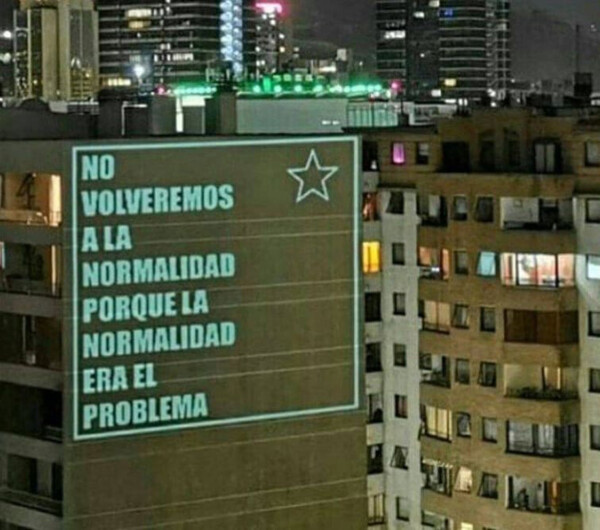

They also believe in art as an effective antidote against the depressive libidinal regime of current capitalism; an antidote capable of shaking our conscience, activating our energies, unlocking our prejudices, assembling our wills and triggering our → imagination to transcend artificial barriers. They believe that art may allow us to envision an exception, a breach in our oppressive and unfair normality and show that “normality was actually the problem”, as says one of the international campaigns in which we are currently involved, connected with the recent protests in Chile.

Figure 1: Anonymous projection in Santiago de Chile during the popular demonstrations of October 2019, used in the campaign La normalidad era el problema, supported by Museo Situado and promoted by Red Conceptualismos del Sur.

The intimate relationship between art and exception became particularly evident during the pandemic, as if the violent suspension of normality dissipated the spell which keeps art senselessly spinning around the art circuits. By the same token, the emergency situation made clear that for art to be exceptional it should renounce its exceptionality, understood as distance and privilege. We thus remembered that art is bound to life; the hunger and the lust for life, all life, and the lives of all.

In fact, the idea of Museo Situado, an assembly in which neighbours and members of the institution would sit and do things together, as Ana Longoni recalls, was triggered by the death of Mame Mbaye in March 2018, a Senegalese street vendor who collapsed at the door of his home in Lavapiés after being chased by the police from the nearby Puerta del Sol. The death of Mame, described by the authorities as provoked by “natural causes”, incited massive protests and a night of riots in Lavapiés. As Ana says, the museum could not be blind to the struggle for life taking place outside of its gates.

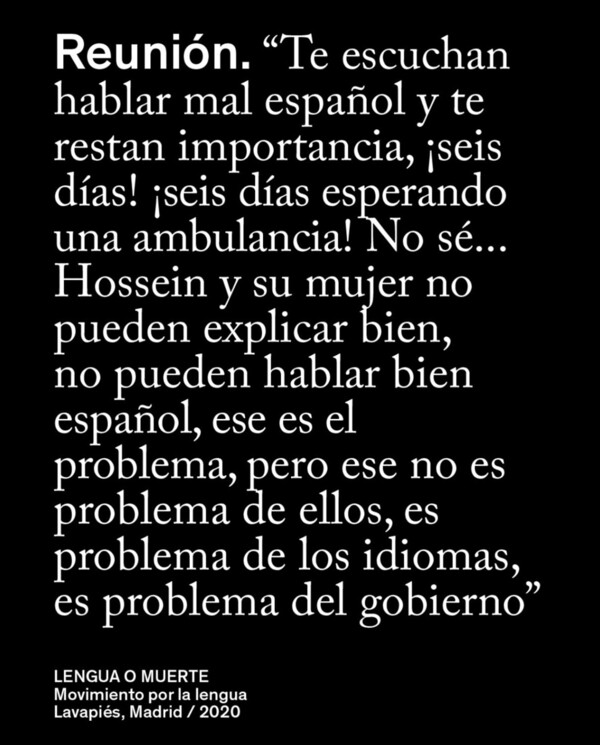

Life and death are also the themes of an art piece conceived and developed within Museo Situado during the confinement: Lengua o muerte (Language or death) by the Argentinian poet Dani Zelko. (Figure 2) He used a methodology called reunión, “meeting”, a collective → process in which he carefully transcribes the words, the silences, the breathings of people whose testimony would otherwise be dismissed, namely victims of state violence. Then, he would produce an “urgent edition”, distributing the book among the community, which would read it aloud.[2]

Figure 2: Cover of the book by Dani Zelko, Lengua o Muerte, Reunión, Madrid, 2020.

In this case, he would record the story of Mohammed Hossein, a neighbour in Lavapiés of Bangladesh origins, who died of COVID-19 on the 26 March 2020 without any medical aid after six days of constant calls to the health service. Nobody could understand the desperate calls of his family and friends, and taxi drivers would refuse to take him to the hospital in a final attempt at saving his life.

Lengua o muerte was produced by Dani Zelko from the other side of the ocean, but with the intimate collaboration of one of the members of Museo Situado, Mohammad Fazle Elahi, leader of Valiente Bangla (Brave Bangla), a cultural association that set up a huge solidarity network to support the local Bangladesh community which had been particularly vulnerable during the quarantine.

How this exception affects the Museum?

A few Museum directors have rushed to announce their intention to move towards what they call “caring institutions”, probably aware of the displacement of social priorities and the danger of becoming irrelevant in the “new normality”. But, as Manuel Borja-Villel already warned us, caring should not involve leaving criticality aside, quite the opposite.[3] Caring is political, as feminisms constantly insist. → Conflictual, as Maddalena Fragnito reminded us in our Glossary’s seminar, and it requires a radical reconfiguration of the art institution in the terms Yayo Herrero so clearly explained in the opening of the seminar. Otherwise, it is mere charity, at best.

Pablo Martínez has reminded us of the dangers of embracing “caring” as an empty signifier, a “new artistic turn”; the latest trend of an art system playing its final piece while the Titanic is sinking.[4] If citizens, together with institutions, do not take a critical stand and participate in the dramatic reinvention of the world that is to come, as pantxo ramas has recently remarked in L’Internationale online article, they will become just “patients” and increasingly efficient vehicles of control, respectively.[5] In a conversation with Marcelo Expósito Ana Longoni emphasised the urgent need to participate in the radical transformation of a “worn-out world”. In order to do that, the Museum must turn away from its hermeticism, and its fortress structure, and, as Ana says, open itself to the vitality and experience of fighting for justice in social movements.[6] That was the original intention of Museo Situado.

Even if I am aware of the resilient nature of the institution, and the powerful magnetism of the “new normality”, I believe that Museo Situado has pierced Reina Sofía to an extent we are still unable to reckon with. The members of the assembly, many of them workers of the Museum, will never forget that “normality was the problem”. It is telling, in this sense, that Lengua o muerte was taken by Reina Sofía as the central piece in the celebrations of the Museum’s day last month.