In museums such as Moderna galerija, and as well as the different art practices form our region, we can find some similar “survival approaches” that we tried to describe with our Repetition series and also Low-Budget Utopias exhibition, both composed of works from our collection.

It seems that innovations or big breaks in art and its institutions are not something that is characteristic of our time, and that we are more or less repeating the forms from the past. But it is exactly in repetition where we can look for radical shifts. Not in innovations inside the existing art genres, but in the repletion of difference between disciplines, different ontologies, and between the present and past.

But there are different reasons why we need so much history in this post-historical time, one can be in that along with history we also lost orientation, general topos, or general intellect. Repetition can be understood also as protection form this loss. The fact that history became one of the central themes for art and for its institutions might lead us to the conclusion that all of this is very much about postmodernism, post-history, post-orientation. If this is true, then we all live in the same post-historical time.

As for Eastern Europe, which has recently undergone major historic changes, history became one of the most important subjects. Local histories in particular are something that is being constantly revisited. Not only historians, everybody does this – from politicians, for whom history is an instrument in their present-day power games, to contemporary artists, who are focused on the → emancipatory potentials of the past and on their present-day erasures.

Similarly, it is very important to distinguish between the different needs and reasons that lead a given cultural space to turn to the past. While quotation, appropriation, collage or pastiche can be defined as typical postmodern approaches, what interests me here is repetition. Repetition is especially relevant when attempting to describe the sustainable museum, and as such it is far removed from the above-mentioned postmodern approaches. The sustainability of the contemporary art museum or of art practices that I will briefly describe here lies in repeating something from the past not because there is nothing new to tell, or because only what already exits is relevant, but because there is an urgent need to retain a difference between what was selected and what was omitted. As Gilles Deleuze would say, what is repeated is never identical with what we select from the past. What is repeated is a difference between different positions, and it is exactly through this kind of repetition that clear statements about the past and present can be formulated.

Figure 1: The Present and Presence: Repetition 3 – The Street, exhibition view, 3 January – 2 June 2013, Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova.

In a series of collection exhibitions that took place at Moderna galerija between 2012 and 2015 under the title Repetition, we repeated the same exhibition nine times as a reference to both the unbearable conditions of our work and to some characteristics of contemporary art. These were defined through a series of re-’s such as abound in the international art and curatorial jargon: redefine, rethink, revisit. (Figure 1)

Figure 2: David Maljković, Again and Again, exhibition view, Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova.

Repetition became crucial for the museum concept that we named “the sustainable museum”. This concept was developed in more detail in the exhibition from our collection entitled Low-Budget Utopias, which initially took up the whole building of the MSUM, but was later reduced by one floor to make room for temporary exhibitions. The first exhibition of this type was Again and Again by David Maljković, whose idea was actually very similar to our concept of sustainability. Maljković’s exhibition referred to the impossibility of a retrospective as an impossibility of an integral and coherent history, and to the necessity that absence becomes an integral part of history. As with all his artworks, his exhibition was only retrospective insofar as it recycled elements taken from his previous works as well as elements taken from previous exhibitions at our museum, old frames, pedestals and even pieces from an installation. (Figure 2) In his work, Maljković refers strongly to the neglected monuments from the history of the so-called socialist modernism. He refers to history and heritage as something that does not concern one single practice or discipline, or a strict division of work. It seems that museums can learn a lot from Maljkovič’s presentation of history. In a museum that incorporates such an artistic approach, a line in art history can jump over into the structure of an artwork or cross paths with themes from the social and political reality, from the immediate environment, from the organic or inorganic nature. This means that the contents of the museum should be in a continual process of transformation, hybridisation, composition and recomposition. But this is not only about recomposing already known elements from history, but also about what is present in our memory and what is not, and exactly in this difference we find a clear position. And a clear position is something that is not characteristic of post-historical time, at least how we normally understand it. What is crucial is to recognise the history or the heritage in these kinds of moments within processes of both becoming and unbecoming. This is also how I understand the following words found in several essays by David Maljković: “Your moment, your heritage.”

The exhibition from our collection entitled Low-Budget Utopias, which is now smaller by an entire floor, refers to different ways of utopian thinking regarding different contexts. Obviously, what we are especially interested in is the East European → postsocialist world. One of the crucial questions asked by this exhibition is which museum model can best serve communities in this region given its specific historical and present-day conditions.

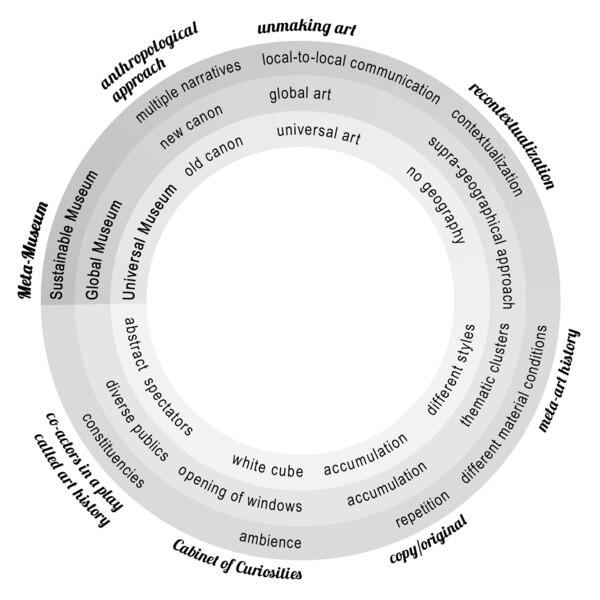

Figure 3: “The Sustainable Museum”, schematics, a part of Low-Budget Utopias, Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova. Courtesy of Moderna galerija.

In the museum space, the exhibition opens by introducing the idea of the sustainable museum. (Figure 3) First we outline the history of our micro-location, the history of our building, part of a former Yugoslav army barracks; next, we present our collection Arteast 2000+, explaining how it serves as a tool for context building and raising awareness of local conditions, and how it can help to establish different international dialogues. Then there is a schematic presentation of four museum models. It is followed by an ambience called Meta-Museum, which includes two installations by Walter Benjamin: The Modern Canon, 2016 (Beyond Art Museums) and Made in China, 2011, which in fact represent the fourth museum model in our schema.

Figure 4: Walter Benjamin, “Museum of American Art”, a part of Low-Budget Utopias, Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova. Courtesy of Moderna galerija.

The four models suggested in our schema are the following: the universal museum, the global museum, the sustainable museum and the meta-museum. The universal and the global museum models belong to the rich Western world and they treat → the rest of the world as a colony. Both of those models look at the world from an abstract position: the position of the former can be described as non-geographical, and that of the latter as supra-geographical. While the universal museum, which can be understood as the modern art museum of the 20th century, collects mostly Western art but introduces it as → universal, the global museum (like MoMA or The Tate nowadays) collects art from all over the world to create one dominant idea of a global contemporaneity. What was once outside the map of “universal art” is today included in the global art map as charted by those who conquered the world. As can be seen from this schema, rather than representing the world through its geographical diversity as expressed through artworks collected by rich museums, the sustainable museum strives for local-to-local communication. It is not built on a counternarrative to the dominant canon, but rather proposes multiple narratives based on different emancipatory positions. These positions can be reactivated with the help of repetition, as I suggested above. In contrast with the accumulation of artworks, which sooner or later become actors in the stories of rich collections, repetition in the sustainable museum keeps difference alive. This means that it makes clear that each collection is a result of different selection mechanisms. Our Low-Budget Utopia exhibition foreground the fact that exhibitions are about composition and recomposition, as illustrated by Maljković’s exhibition; a retrospective offers an opportunity to see his works as an infinity of different relations. The fourth museum model in our scheme is also an artistic project, and as such it takes the museum of modern art as its subject. Two installations, the Museum of American Art and MoMA Made in China, show that the modernist canon can now become subject matter for contemporary art or for the contemporary art museum, so that what was once the principle of artistic development is now merely an object contemplated from a distance. As Walter Benjamin would have said, any museum based on a single narrative and on a corresponding accumulation of artefacts is unsustainable in the long run. The sustainable museum counters accumulation with → self-reflexion, contextualisation and repetition. Benjamin with his MoMA presentation repeats records of surveillance cameras in its collection presentation. Mimicking the surveillance camera perspective, he repeats not only the exhibition look but also the system of values of modern art that is protected again and again with reproductions, also those ones done with surveillance cameras. (Figure 3)

The following quote from Walter Benjamin inscribed on a wall at our museum suggests that learning is not necessarily limited to the rich world:

The Museum of American Art (MoAA) is a meta-museum whose main subject matter is the Museum of Modern Art in New York as the founder of the modern art canon. It is a place from which we could observe the history of MoMA and the shaping of the modern narrative while at the same time being outside of it. However, while the MoMA today is a multimillion dollar enterprise, the annual budget for MoAA is less than ten thousand dollars. This shows that, with very humble means, it is possible to define a meta-position which is out of the reach of mega-museums like MoMA.

The sustainable museum is a museum capable of operating in a low-budget environment by drawing on its own resources for its developmental potential. If the universal and the global museum can only operate as part of the cultural industry, the sustainable museum can still be a place where we learn from each other without making a profit. In the confederation L’Internationale we talk about → constituencies, about → interdependency between different agents in a community – artists, various interested individuals, socially engaged groups and organisations. Both its community and the museum itself are continually being transformed by these constituencies through mutual coordination and discussion. Along with developing conditions for such participation and interaction, the sustainable museum also continually reimagines and redefines itself by means of the collections and → archives it holds.

Unlike the universal museum, which presents its idea of modern art as a totality, or the global museum, which attempts to cover the entire world by filling its depositories with artworks, the sustainable museum strives to process and reveal the possibilities within its own environment and to develop local-to-local → alliances based on similar → interests and visions.