The history of → solidarity as a notion identified, observed and studied as a practice inherent to communities and societies, long predates modernity. The sociologist Emil Durkheim understood Ibn Khaldun’s concept of ‘asabiyyah as a version of solidarity. Its etymological origin is attributed to the French solidarité, that was first coined in the 1765 Encyclopédie, and seems to have gained currency around 1841, specifically with a close association with → labour struggles. While solidarity became a seminal notion to the 20th century’s political lexicon, its meanings and implications seem deceptively unambiguous and straightforward. There is the expression of collective will (whether voluntary or coerced), the conscious basis for collective action, as well as the principle for the establishment of organisations or the paradigm headlining international diplomacy. In reality, solidarity is a vexing, complex and misleading notion, perceived at once to be “organic”, almost inevitable, to produce change immediately and effectively (especially for the labour movement and Marxist discourse), but at the same time to be slow to coalesce, and not to systematically impel a forward-looking, progressive, correctively egalitarian or transformative movement. Looking at the US labour movement, for instance, whose paradigmatic anthem is titled Solidarity Forever, the work of David Roediger, and Alexander Saxton has uncovered the racist origins of working class formation, and how, for decades, the movement’s prevailing narrative has been primarily a history of white male workers. In Marxist discourse, the contradictions of capitalism and workers consciousness logically, or “teleo-logically”, produce a unified oppositional political force grounded in solidarity that leads to action and produces profound change.

Solidarity has also produced an impressive iconographic, musical, literary and cinematic patrimony, as artists have been invariably mobilised to produce representations, narratives and a cultural repository to the political struggles that produced solidarity movements. As 2018 marks the fiftieth anniversary of May 1968, the countless exhibitions of visual art, film programs and cultural congresses, worldwide, attest to the wealth and relevance of these diverse patrimonies, and the central role of creative expression in mobilising and memorialising solidarity.

Between 2009 and 2017 I conducted research around “solidarity art collections” and “museums in exile” in collaboration with the researcher, writer and curator, Kristine Khouri. Together we traced and examined the intersecting transnational histories or four case studies, namely the Museum of Solidarity for Chile (1972-1973), and its subsequent iterations as the Museum of International Resistance Salvador Allende (1974-1990); the International Art Exhibition for Palestine (1978-1982), (Figure) intended as a seed for a museum in solidarity with Palestine; the Art Contre/Against Apartheid (1982-1994); and the Art for the People of Nicaragua and its subsequent iterations as the Museum of Latin-American Contemporary Art of Managua, and the Art of the Americas in Solidarity with Nicaragua. The notion of a “museum in exile”, perhaps counter-intuitive and even perplexing, referred to a collection of art works donated by artists to attest of their support for a political cause. The collection travelled to museums worldwide (and sometimes to non-art specific places) with the mission of raising the awareness of a wide public, giving the cause legitimacy, and generating solidarity. Once the political struggle the “solidarity collection” or “museum in exile” incarnated and achieved its goals, it was supposed to become a museum in that country. In some cases, the administration and management of the collecting and touring was done by professionals in the fields of art and culture (curators and gallerists), but in others by a small group of artists.

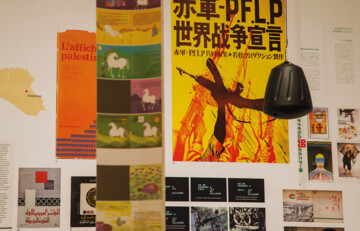

Past Disquiet: Narratives and Ghosts from The International Art Exhibition for Palestine, curated by Rasha Salti & Kristine Khouri, exhibition view, Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, 2014. Photo courtesy of MACBA.

In art history, exhibition history, or museology, these museums in exile/solidarity collections are almost entirely absent. By virtue of the impetus behind their existence, and of their constitution, they run against the grain of modern and contemporary paradigms of 20th century modern and contemporary art museums. They were established entirely outside the schemes of patronage, the legacies of colonial and imperial domination, and wealth accumulated from exploiting people and/or natural resources. They stand as emblems of a political ideal, wherein the transnational and national intermingle entirely uninhibited from ethno-cultural trappings of nationalism, and rather represent the sovereign political will of artists, curators, intellectuals. They are also registered as a patrimony to a people. The research into how they came to be revealed captivating networks of → collaborative work among artists, intellectuals and militants across the world. In parallel to their respective practice as individual artists, what Kristine Khouri and I discovered was an under-written history of actions, interventions in public spaces, participation in protests and strikes, as short-lived collectives producing placards, posters, banners and painted murals. Mapping these activities brought to light surprising findings, namely close connections of artists with unions and other militant organisations (fighting for social housing, gender rights, immigrant rights, etc.), tight collaborations between international artists who had found asylum in Europe, sometimes across the Iron Curtain, and tight connections with the so-called “→ Global → South”. High-profile events such as Documenta and the Venice Biennale hosted these militant practices in peripheral programming.

These four cases of “solidarity collections” were launched during the Cold War, in the heart of what was known as the worldwide anti-imperialist solidarity movement. The causes that rallied artists across the world intersected transversally, opposition to the US intervention in Vietnam, the struggle against Pinochet’s dictatorship, the fight to unseat the apartheid regime in South Africa, and several liberation struggles with the Palestinians at the helm. In the context of the Cold War, the notion of solidarity carried complex multi-layered connotations. In the geography known formerly as the pro-Soviet Eastern Bloc, solidarity was a state-sponsored instrument of diplomacy, a creed that trickled top-down from government bodies to artist unions or associations. This was in contrast with its deployment in the western flank of Europe, where it crystallised as the expression of radical grass-roots political engagement, that moved from the bottom upwards. The solidarity interventions conducted by artists after May 1968 have been overlooked by art historians, critics and curators, because in most cases the artists did not belong to an “avant-garde”, or their practice did not propose radical or innovative formal or aesthetic language. In the case of the artists from the former Eastern Bloc, the artists who participated in solidarity actions were those officially sanctioned by the government, or in other words “official artists” whose motivations may not have been genuine.

Some of the interviews we conducted with artists from Poland and the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), who took part in solidarity actions against the Pinochet dictatorship and in support of the Palestinian struggle, respectively, confirmed this thesis. However, we also recorded other testimonies that challenged it. The case of the German artist Günther Rechn was an interesting case in point. Rechn and four other artists from the former GDR visited Lebanon twice, in 1979 and in 1980, answering an invitation from the Union of Palestinian Artists (UPA), one of several elements of the official protocol of collaboration between the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and the government of the GDR. The artists visited refugee camps, met with Palestinian freedom fighters (fedayyeen) and Palestinian artists. They produced work that they exhibited on their second visit in Beirut. While perusing Rechn’s sketchbooks, we fell on a portrait of a man clad in the emblematic kuffiyah that fedayyen characteristically wrapped their heads with. We asked him where he met the man and whether he had agreed to pose for him. Rechn replied that it was in fact a self-portrait. We were startled because it transgressed our expectations of the regime of images and representations of state-sponsored solidarity. The identity switch, the subversive and surreptitious substitution of representation, was a transgression of self and other, beyond the “rules of the game”. Rechn’s case underlines how the agency of the artist challenges wholesale assumptions about subjectivity and solidarity under totalitarianism.

What of solidarity today? While neo-liberal capital seems to have ended the currency of any form of social welfare systems, the notion of “the common” has resurged as a site of ideological, intellectual and anthropological resistance, the notional and practical soil for discovering and theorising political alternatives. Solidarity, however, is still lacklustre, sometimes tainted with cynicism, and the necessity and urgency for its revival is still latent. For instance, there has not been a dedicated issue of the e-flux journal, or international conferences, or Documenta projects dedicated to exploring and revisiting solidarity, as has been the case for “the common”. There are nonetheless “symptoms” of solidarity – like the Avaaz.org and Change.org internet-empowered petition templates – that are as much a testament to their efficacy as their failure. There are also international campaigns calling for the boycott of goods, or divestment in national economic institutions and corporations, such as the one currently targeting Israeli public and private institutions and companies, to pressure the Israeli government into ending the military occupation of Palestine.

If we consider the modest realm of our own industry and trade, namely the world of contemporary art, does solidarity level currency? In contrast with other intellectual disciplines, the extent to which the logic of neo-liberalism prevails over the realm of the métiers in contemporary art is daunting. The criteria for success and failure, reward and sanction, and job security, are almost entirely ruled by the logic of the market (even within state-run institutions) and by perfidious perceptions of meritocracy. There are also “symptoms” of solidarity. Almost at a yearly rate, at least one curator is unjustly dismissed and humiliated because of exasperated patrons or offended publics, and a petition goes viral from mailbox to mailbox, in a gesture of solidarity. Some sign it because of empathy and/or affinity; others so as to safeguard the principle of job security or freedom of expression. There are also petitions dedicated to mobilising outrage against the abuse or sentencing of an artist, the shutting down of an institution, the sale of an archive or a collection. The question is not whether such petitions are useful or not, some do lead to the release of a detained artist, writer, or curator, while others provide emotional and psychological support for an aggrieved colleague in difficult times. The question is whether real solidarity is effectively imaginable in our professional milieu, knowing that we, cultural workers, operate under extremely precarious conditions in the present world order.

In a keynote address at the American Sociologist Association (ASA) annual meeting in 2015, David Roediger offered critical thoughts on the significance of solidarity in our times. He aptly noted that solidarity should be “uneasy”, rather than straightforward, obvious and efficient, citing Chandra Talpade Mohanty, he reminded us that solidarity is “not a being but a doing”. In The Cultural Politics of Emotion, Sarah Ahmed offers an important insight in that vein: “Solidarity does not assume that our struggles are the same struggles, or that our pain is the same pain, or that our hope is for the same future. Solidarity involves commitment, and work, as well as the recognition that even if we do not have the same feelings, or the same lives, or the same bodies, that we do live on common ground.” I will borrow Roediger’s conclusion for this essay, which he phrased as an invitation: “let us seek solidarity “by owning its difficulties”. Is solidarity in the professional fields of art and culture an idea whose time has not yet come?