Despite many claims to the contrary, postsocialism and post-communism should not be considered synonymous. Socialism may have been a political philosophy that communist parties in various parts of the world claimed (however inaccurately) to promote, but it was also – and perhaps most importantly – a philosophy of great relevance beyond communist governments. Its politics have long underpinned broader oppositions to capitalism and the oppression it can engender, whether in the “East” or “West”, “North” or “South”. From the welfare states of Western Europe or Australasia, through to the social democracies of Scandinavia, its principles have underpinned the drive for more equitable redistributions of wealth and opportunity across societies. The development (and, to an extent, the sustained support) of the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom, is unthinkable without the socialist ideals informing the Keynesian thinking of the post-war welfare state. The development of Medicare in Australia in the early 1970s – along with increased social welfare, free tertiary education, higher tax rates for the wealthy and the creation of a nationally-funded council for the arts – finds its foundations in comparable socialist ideals.

Similar politics have equally informed the rejection of privatised finance as our lingua franca – the “financialisation” of discourse, of social relations, of “being itself” that is so characteristic of neoliberalism – and instead supported different ways of imagining international and geopolitical connections. Some of the most recent instantiations of this emerge in the social justice movements in Athens, in Madrid, in New York, and in the numerous and interlinked fights against corporate welfare and working poverty. These protests find at least a part of their roots in similar resistance towards state-endorsed capitalist neo-colonialism from the not so distant past: in the struggles for decolonisation across Africa and South Asia, for instance, such that the first national constitutions after decolonisation were often explicit in their socialist ambitions for the new nations. Or in the political ambitions of the Third World International and of the Non-Aligned Movement, the remnants of which have persisted in social, cultural and political calls for a new kind of non-alignment, a new International, today.

To limit postsocialism to what has happened in post-communist states, and especially to conditions in Central and Eastern Europe, is certainly understandable, given the range of important literature on “postsocialist Eastern Europe” (Katherine Verdery, Marina Gržinić and so on). Yet that limitation arguably ignores (post)socialism’s more properly international scope and its broader struggles against the neoliberal revolutions since the early 1970s. Postsocialism, to my mind, suggests an important international connectedness in an age of globalisation – albeit a connectedness that contains within it senses of the past and the future that differs from the more amnesic frameworks (or opportunisms) connoted by globalisation. To speak of postsocialism, then, rather than neoliberalism or globalisation per se, is to remind us of what has supposedly been lost since the 1970s and 1980s, but which may still resonate some 30 to 40 years later, and to assert contemporary perspectives and historical trajectories that lie beyond those of the North Atlantic, that have largely been marginalised after socialism’s apparent collapse.

To insist on the social rather than the individual, and on translocal solidarities rather than global competition: if these are some of the cornerstones for a more viable and more sustainable geopolitics today, and I think they are, then how might the various politics, aesthetics and ideas developed during socialism, or for socialism, respond to our condition today? What might it mean, for instance, to be “nonconformist” or even “dissident” (for all the problems associated with those monikers) in our supposedly post-ideological contemporaneity, and who might be the progenitors of these politics?

Figure 1: IRWIN, NSK Embassy Moscow plaque, 1992. Courtesy of the artists.

I want to draw on two artworks – or, better still, art contexts – that may help to elaborate these questions. The first is a year-long event devised by Lena Kurlandzeva and Konstantin Zvezdochetov from Moscow’s Regina Gallery, and the independent curator Viktor Misiano, staged in Moscow in 1991–92, called Apt-Art International. The renowned NSK Embassy Moscow, from April-May 1992, is perhaps the most significant of the projects from Apt-Art International (Figure 1), but it was just one of 12 or so projects devised for a cumulative purpose: to draw on Moscow’s histories of apartment art from the 1960s to the 1980s, as the basis for imagining a new international model for displaying and talking about art after the upheavals of 1989–1991. The crux of Apt-Art International was not merely to bring artists and thinkers from different contexts together in Moscow’s art world – though this was clearly very important. It was also to review the new world (dis)order in art and politics alike after communism, and to engage these new inter-cultural dialogues, from the fragile perspectives of those who lived under communism – and, most potently, to do so by re-engaging the models and past prospects of apartment art, on the verge of obsolescence amid this new (dis)order.

On the one hand, then, this “new internationalism” could potentially emerge from the position of the supposedly “vanquished”, developed through heated debate and even disagreement about the ongoing efficacy of the old apartment art models (a nod in itself to the often conflicted histories of past apartment art, including the sense that even in the 1980s it was just a nostalgic revisiting of notions of nonconformism). On the other hand, it sought to use apartments as sites for connecting hitherto disparate contexts – that of NSK in Ljubljana, or Sol LeWitt in New York City, or Franz West in Vienna – in order to find points of connection and even of commonality, despite ideological divides, from which to draw socialist and communist thinking back into the future.

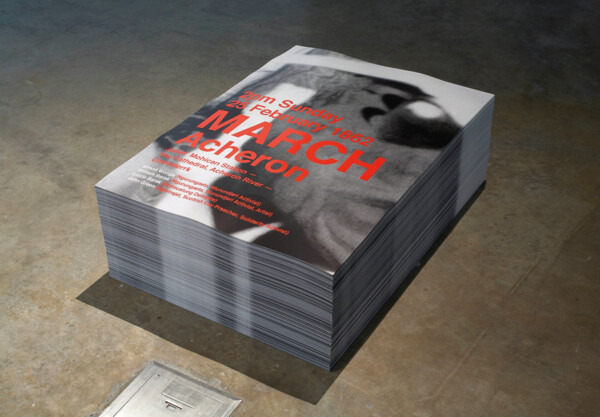

Figure 2: Tom Nicholson, 2pm Sunday 25 February 1862, flyers, 2005. Courtesy of The Gallery of South Australia.

The second work I want to bring into a discussion is by the Melbourne-based artist Tom Nicholson. 2pm Sunday 25 February 1862, from 2005, consists of a stack of posters proposing a march towards a small Australian town called Acheron, led by three Indigenous Australian activists (Simon Wonga, William Barak and Lizzie Barak) and a non-Indigenous “solidarity activist”, as he is listed on the poster, named John Gree. (Figure 2) The posters suggest a memorial to, or perhaps the re-enactment of, an important though (for some people) forgotten moment in Australian colonial history. This was the long march made by Wonga, Barak and other Indigenous activists, together with the Scottish missionary Green, in the early 1860s from one country (belonging to the Wurundjeri people) to another (that of the Taungurung people). The march was an act of extraordinary dissidence, defying the demands of the “Aboriginal Protection Board” (a government authority that exerted strict control over the country’s Indigenous populations) that the people stay where they were. Yet it also ultimately led to the creation of a new semi-autonomous centre in a town called Coranderrk, where the Indigenous marchers lived and worked in relative prosperity and collaboration with settlers, such as Green and his family.

Regardless of whether his poster (or, to use the term Nicholson prefers for this kind of work, his “action”) was a memorial, a proposal for an event long past, or a call for re-enactment, Nicholson did not intend for the march to ever be actualised. While its retracing of a kind of dissidence in Australia suggested a foundation in the past for future transcultural relations, that foundation had been made fragile by decades of neglect and racism. Conversely, if the poster proposed a meeting and march by Wonga, Barak and their families, then that projected march was to come nearly 150 years too late. Nicholson’s proposed intersection of different temporalities, actions and cultures thus remained open and precarious, an uncertainty reinforced by lingering doubts about the viability or potency of the poster as a medium of political action.

Central to the work, in other words, is a persistent sense of haunting: the haunting of art’s political relevance by its uncertain efficacy; the spectres of dissident histories as a possible action in the present; the dialectic of erasure and recall within artistic and political memory. But what is just as important within these recalled histories is the past possibility and dogged demand for horizontal cross-cultural relations in Australia between its Indigenous and settler populations. In the 1860s, these relations were deeply inspired by a liberalism drawn (as was certainly the case for John Green) from a mix of Christian instruction and working-class politics of union and solidarity, grounded in the early transposition of Marxian thinking into colonial Australia. By 2005, such returns to the 19th century birth pangs of socialism in Australia had become a common feature in Nicholson’s work, albeit presented in different ways. Some works were displayed atop trade union buildings; others involved the procession of huge banners in ostensibly political marches past the same buildings. In each case, however, Nicholson drew socialist and anti-colonial histories together to emphasise the need to re-evaluate local histories (of exchange, of collectivity, of labour, of culture and of politics) within the depoliticising amnesia that tends to characterise the neoliberal contemporary.

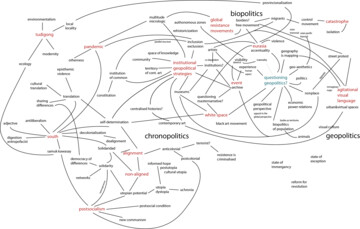

Postsocialism, I want to suggest, is thus a possible way to think of the solidarities envisaged by and between these two, quite different projects (as well as many others, of course, such as the return to Indian socialism in the work of the Otolith Group or the renewed interest in cultural formations of the Non-Aligned Movement). It operates across both space (geopolitics) and time (chronopolitics), yet does not eradicate the distinctions and memories of socialism as engaged in different localities (something that distinguishes its internationalism from the spatiotemporal and cultural flattenings of “globalisation”). Nor does it dispense with the challenges faced by recalling socialism today, whether because of the years or even decades since its supposed withering, or because of the traumas inflicted in its name. Yet, the need for an international → solidarity [→ solidarity] [→ solidarity] that can “generatively” counter the traumas inflicted by other hegemonic politics (North Atlantic neoliberalism, the authoritarian capitalism of Singapore or China, the destructive forces of petrodollar-funded Wahhabism) is as important today as at any point in the twentieth century. Moreover, that solidarity is one that must respond to current and imminent crises that have little respect themselves for national and political borders: from refugee crises to the financialisation of subjectivity (perhaps of everything), and environmental → catastrophe. The question, then – and it is a question posed equally by the postsocialist undercurrents of Apt-Art International and Tom Nicholson, among others – is whether a new international solidarity could ever really emerge as a significant politics without thinking of socialism, its aftermath and its lingering potentials?