In the last decade of Yugoslavia’s existence, when all that remained was pretence of believing in the socialist system, the collective Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK) engaged in a reckoning, not only with the extent government but also with the gradual disappearance of a firm symbolic order; this was not simply a problem with the state of Yugoslavia but a universal subjective disorientation in the contemporary world.

The NSK collective was founded by three groups sharing similar retro-avant-garde concepts, Laibach, Irwin and the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre (SNST), in the Orwellian year of 1984, the moment of transition of a society of discipline to a society of control.

Laibach’s 1982 statement reflected not only totalitarian impulses in the Yugoslavian one-party system, but also the general colonisation of subjectivity by the Big Brother that was the epistemological, monetary, religious, cultural and media domination and the power of technological control exerted by the West: “All art is subject to political manipulation, except for that which speaks the language of this same manipulation.” About a decade later, Slavoj Žižek characterised this type of approach as over-identification: The strategy of Laibach “’frustrates’ the system (the ruling ideology) precisely insofar as it is not its ironic imitation, but over-identification with it – by bringing to light the obscene superego underside of the system, over-identification suspends its efficiency.” There is no need to underline how irony and criticism best serve the system itself, especially the capitalist system. In his writings from the late 1980s and early 1990s, Žižek emphasised that the uneasiness triggered by NSK even in some left-wing critics of the system stemmed from the fact that the collective had never assumed a clear and unambiguous critical distance from the government, and from the assumption that ironic distance is automatically subversive.

One of the heights of provocation, which was among the main tools of NSK in the 1980s, was reached in 1987 with a poster for the Day of Youth, a holiday celebrating Tito’s birthday. New Collectivism, the design group within NSK, took part in the national competition for the best Day of Youth poster. They based their entry on a 1936 Third Reich → propaganda painting by Richard Klein and won. Part of the reason may be that the poster reminded many of socialist-realist art, the memory of which was already being eroded in Yugoslavia. The artists kept the athletic male figure, but removed the Nazi symbols and replaced them with Yugoslav ones: the Yugoslav tricolour of red, white and blue, the five-pointed star, the six torches from the Yugoslav coat of arms representing the six republics of Yugoslavia, and a white dove. These symbols replaced the Germanic eagle, the Nazi flag with the swastika and the coat of arms of Nazi Germany. This montage was only noticed by the government after the jury had already proclaimed the winner; what followed was a scandal beyond compare in the cultural history of post-war Yugoslavia. Žižek wrote about the poster affair in “A Letter From Afar” in 1987. In that essay, he emphasised that NSK “draws attention to the fundamental phantasms, the phantasmic myths and constructs on which our national identification is based. But it does this in such a way, through a whole range of alienation processes (the montage of heterogeneous, incompatible constructs; the reiteration of the phantasmic construct in its literal imbecility, in the exposed shape that must remain hidden in everyday life, etc.), that we are able to achieve distance from these phantasms.”

It was Laibach that first started moving signs from one context to another, beginning with the group’s very foundation in 1980 when it chose to call itself after the German name for Ljubljana. Numerous public reactions as well as the official prohibition of the name in the years 1983 – 1987 show just how jarring this choice was given the still enduring memory of the occupation of Ljubljana during World War II when the German name for the city was last in use. One of the fundamental constructs of post-war Yugoslavia, the basis for the national consciousness in Slovenia and elsewhere in Yugoslavia, was the partisan resistance to the occupier. All that the post-war mythologisation of the national liberation struggle served for was obviously empty state rituals.

In addition to the name, Laibach’s key symbol is the cross. The Laibach cross does not refer only to Kazimir Malevich’s suprematist motif, but also to the black cross that marked German military vehicles and aircraft during World War II. The black Laibach cross on posters, on fanzines, on paintings, on the sleeves of the members’ uniforms, on flags at concerts, on albums, does not serve any social identification purpose and is simply a sign of social fascinations. Žižek wrote, on various occasions, that NSK’s metaphors brought their opponents face to face with their own nightmare, which does not tolerate reflection, with the unbearable core of the pleasure made possible by the limits set to us by the big Other.

On the one hand, NSK performs the roles of totalitarian types in Nazi or socialist regimes; on the other hand, and at the same time, it speaks about the repressive power of the media and about the totalitarian impulses in Western pop culture, where the boundaries laid down by the master have become unrecognisable. From the very beginning, Laibach has been uncovering, through its performances and music, the obscene aspects of both Eastern European and Western societies, including by citing Western hits at various points in its discography; one such example is Laibach’s song “Geburt Einer Nation” from their album Opus Dei ( 1987), copied from Queen’s 1985 song “One Vision”, except that it is in German. (“One Vision” was inspired by concerts where the audience in their thousands automatically repeated the band members’ gestures.) Global popular culture and global technological control have remained at the centre of Laibach’s interests until the present day, for instance in their song “The Whistleblowers”: “From North and South / We come from East and West / Breathing as one / Living in fame / Or dying in flame”. Here, Laibach draws attention to heroes like Edward Snowden and Julien Assange, who resist contemporary totalitarianism.

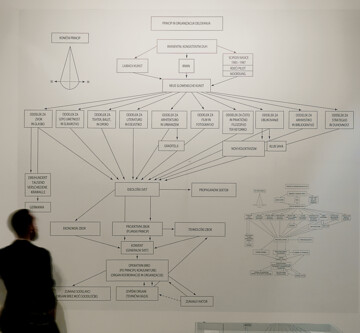

While Laibach today has a more pop-cultural image, in the 1980s it was much more explicitly totalitarian and bureaucratic. The entire NSK at that time worked on deconstructing the state, its ideology and artistic system, including through hierarchical organisation schemes, manifestos, programmatic texts, declarations, interviews with pre-written programmatic statements. All these texts and schemes speak about the subjection of the individual to the collective, or in other words, about the ideology replacing an authentic form of social consciousness.

It could be said that through its manifestos, NSK wanted to take the place of the Other. The non-functioning of the other has also been noted in manifesto form by Alain Badiou. By deciding to write philosophy in the form of a manifesto, Badiou drew attention to the importance of actualising philosophical endeavours. The actions of NSK and Badiou resembled those of the early 20th Century avant-garde. For Badiou, the mobilisation potential of a manifesto does not stem only from its future-oriented contents, but from its producing and subjectivising the present.

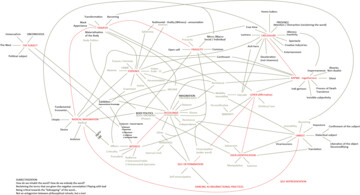

Ever since their founding, the central theme of all the NSK groups has been the state, both a specific state, whose national myths appear in their work and the state as an abstract organism, the law on which all concrete ideological constructions are based. Thus, NSK did not only deal with the dissolution of Yugoslavia but with the dissolution of the symbolic order in general. This is why NSK never was a typical Eastern European dissident art project since the collective was more interested in finding out to what extent the big Other was still operant than in providing clear, unambiguous criticism of the extant regime.

In NSK’s work, the concrete state of Yugoslavia was only a singular manifestation of the abstract organism of the state, but also, paradoxically, a foreshadowing of another concrete state - that of independent Slovenia, formed in 1991. Based on this, it could be concluded that with the founding of Slovenia, what NSK predicted came true and that in this sense NSK’s might even be nation-building art. It may have been in order to avert just such a fatal misunderstanding that in 1992, NSK founded the NSK State in Time, fundamentally distancing itself from the nation state as well as from the national culture.

It is true that this distance had been maintained by the NSK since the very beginning. To start with, the naming of the collective itself was a performative gesture. The act of its naming appeared to be a call for a new national art, but at the same time, NSK distanced itself from such art by using the German language.

The founding document of the Irwin group calls for a new Slovenian art, but at the same time, it describes such art as deeply eclectic and over-identifies with this very eclecticism, with the impure culture of small nations on the edge, through its principle of potentiated eclecticism.

The SNST over-identified with the state that is somewhere between a real state existing in this world and the city of god as described by St Augustine. The SNST’s ways of spreading their ideas included so-called sister letters. In the first sister letter, they stated that the theatre was the state.“The outer, manifest part of the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theater presents an image of a solid and geometrically utopian Existence, whereas its creative inner part is an image of the conflict between Emotions and Style in their inevitable and all-renewing sacredness.”

As stated above, the whole of NSK’s work reflects the problem of the non-functioning of the state, a particularly tragic real-life manifestation of which was the war in BIH. With regard to this Žižek says that the war in BIH may have been a consequence of an absence of a unified state authority above ethnic divisions. He speaks of the NSK state as of a contemporary utopia of a new state, a state without a territory, an artificial structure of principles and authority.

The NSK State in Time, which may now be the largest artistic state in the world, counting 14,000 members, has become independent of NSK itself and is governed by its members. Today, this artistic state draws attention to the importance of idealist visions for the survival of the state in the sense of shared principles and laws, without which no human society can function. When artists take the law into their own hands, they most certainly do become political subjects.