Figure 1: Vaast Colson, Library, 2016. Courtesy of the artist © M HKA.

Sometimes – in fact quite often – terms are coined “in action”, to help encapsulate a particular → event at a particular point in time. There is a need to say something that is felt to be important, an already existing word is grabbed, and this will do for the time being. Later, when those who were not present at that decisive moment try to make sense of the “new” term, they may struggle to grasp its retrofitted usage. This was the case with “revolution”, which before 1789 articulated pretty much the opposite of what we mean by it now: regular, phlegmatic, cyclical movement in a direction that could be described as “forward”, but without any sharp twists and turns. (Figure 1)

Constituency, in the plural form now used within the L’Internationale confederation, is another such term. It reappeared in Spain just a few years ago, to describe a new → constellation of intellectual and socio-political forces that has already brought two of our former colleagues at Reina Sofía into very visible positions as chief cultural officers in the country’s two largest cities. A new generation of political activists in Madrid, Barcelona and elsewhere in Spain has turned a term that used to describe the technology of politics (the organisational geography of elections, the target group for almost personalised propaganda) into a potent verbal tool. They appear to be moving along a trajectory starting with the “constituents” of politics and leading towards a revision of its “constitution”.

At M HKA, a contemporary art museum founded and funded by the Flemish Community, we are now developing an understanding of what we could do with constituencies in our particular segment of reality. We try to combine an intuition of how to reformulate our relationships with “audiences” and “the public” (terms grounded in the nineteenth-century “shareholder society” for the well-to-do) with a quest for the truly new in art and exhibition-making and museum research (which can never be produced or procured “by committee”). We wish to go beyond the adaptation of a clear, enforceable definition of “constituencies” in terms of mediation or outreach or learning or any other politically correct term for what the museum should do to the society that sustains it. As part of our thinking process, we have glanced through the last two centuries to try and detect a pattern that might suggest a way forward for constituencies as a productive term.

If the French Revolution meant turning the subject into a citizen, the Reaction of 1815 and the “long nineteenth century” of bourgeois capitalism and European imperialism somehow re-subjected the newborn citizen, but now as a shareholder (making sure that those exploited by the system also had a share in it, as it were). Then, after the First World War, the pendulum swung back and the subjects of Empire and Industry again had to be treated as citizens: the liberal democracies gave them voting rights; post-revolutionary Russia addressed them as “comrades”; even in the colonies they could no longer be completely ignored.

Those parts of the world that considered themselves “free” (from totalitarianism) after the Second World War focused on rebuilding the economy, with certain concessions to ideas of equality, and there was a general and gradual drift from treating individual members of society as citizens (with rights and obligations) to wooing them as clients (with the obligation to choose freely from what was being offered). There were also interesting debates about “economic democracy” but these became overshadowed by the Cold War. Towards the end of these “glorious thirty years” New Public Management and neoliberalism (but also well-meaning advocates of a sustainable democratic order, for instance in Scandinavia) introduced new words for the client, such as “user” or “stakeholder”.

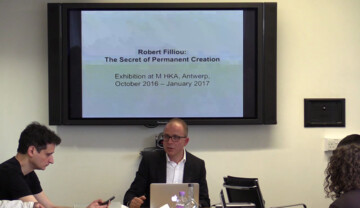

Figure 2: Robert Filliou, The Secret of Permanent Creation, exhibition view, 13 October 2016 – 22 January 2017. © M HKA.

And now, if we can decide on the best way to use “constituent”, we might have found the term that describes the movement back from client/user/stakeholder to the citizen as an active subject (in that other sense that stresses subjectivity rather than subjection). Yet at M HKA we prefer to test the new term in practice first, before fixing what it will mean to us in the medium-to-long term. At this point, therefore, we wish to propose another term, borrowed from the late economist and poet and playwright and artist Robert Filliou. He is the subject of a retrospective this autumn, titled The Secret of Permanent Creation, which I’m now working on. (Figure 2) I quote from the catalogue of Filliou’s first retrospective in 1984:

Eternal Network Création Permanente La Fête Permanente Geschehen Poetic Economy: At the end of La Cédille Qui Sourit [in October 1968] George Brecht and Robert Filliou founded the Eternal Network, La Fête Permanente: “The artist must realise also that he is part of a wider network, La Fête Permanente, going on around him all the time in all parts of the world. We will advertise also as alternative performances such things as private parties, weddings, divorces, lawcourts, funerals, factory works, trips around towns in buses, pro-Negro manifestations or anti-Vietnam ones, bars, churches, etc. …

The conscious “mistranslation” into French should be seen as an indication of Filliou’s bilingualism. He studied economy in California in the late 1940s before taking a job with the United Nations, but in the mid-1950s he quit and dedicated himself permanently to creation. The morale here is quite obvious: that those who are well versed in different systems (or languages) are best positioned to explore and pursue what links them. It was Marianne, Filliou’s Danish-born wife, who once remarked: “You’re artists when you create. But when you stop, you’re not artists anymore.” This alerted Filliou to the necessity of Permanent Creation, which would become his overriding concern: a true opening-up of practice to the world, and of the world to practice.

This is how we at M HKA believe the meaning of the term “constituencies” can be explored and pursued most creatively and efficiently. As we set out to look for our constituencies, we realise that we have to create them ourselves, through our own acts and activities. And then we mustn’t forget those primary actors in the field we’re covering: the artists.

One of our operative goals, as stated in our current policy plan, is to be “an open house for artists”. Rather than regarding this as a particularised aspect of our work, or even just a feel-good measure to appease local sensibilities, we should see the artists we → collaborate with as a crucial constituency that may help us radicalise everything we do – by never sacrificing the specificity of whatever it is that artists do. As Robert Filliou also said: “Art is what makes life more interesting than art.”