I will hear → the dead speak

So the world is not as it is

Though I have to kiss a living face

To live tomorrow yet.

Washington Delgado, To Live Tomorrow[1]

It´s been more than a year since I first looked into → travesti[2] memories with a researcher’s eye, wandering around the atelier that the artist Javi Vargas Sotomayor rents in the middle of the noisiest side of central Lima. Those streets, once sparkled with cinemas and cantinas that hosted all kinds of clandestine bodies and desires had been totally transformed due to hygienisation policies and showed a renewed face in which only the street vendors known in Peru as ambulantes resist the erasure of any sign that contradicts the postcard image of a “decent”, “clean” and above all “safe” city to visit and invest in.

Some of those cinemas have turned into ultraconservative evangelical churches that nowadays are at the front of the anti-LGTB+ and women’s rights movement, and the cantinas are nowhere to be found. Only one unusual, singular spot remains almost exactly the same. In the middle of Sebastián Barranca street, there is a car mechanic workshop in which close to thirty years ago an effigy of the Virgen de la Puerta was placed. During the 1990s that particular neighbourhood, one of the poorest – if not the poorest – of Lima, damaged by AIDS, tuberculosis, hunger, drugs, unemployment and severe poverty in general, also became the home of a unique community of almost fifty travesti women. They fully inhabited a few buildings and shared rooms and bathrooms, worked the nearby streets, played volleyball for the amusement and entertainment of their neighbours, escaped the police, received the visits of NGO volunteers and interventors, opened hair saloons, shaped their bodies, practiced their faith, got sick and died.

It is difficult to think of times when old age has been more in the spotlight than these. And it’s difficult to think of a community more excluded to the possibility, even the right, to age than these travesti women, whose life expectancy only recently rose to about 45 years. In fact, it is hard to think of a community more marginalised and erased in history than travesti women, and thus it is easy and somehow understandable that when they are considered is usually through the filter of victimhood, as agonised beings and subjects of suffering. It is through the impeccable work of Giuseppe Campuzano,[3] who became enchanted and absorbed with so much respect and awe for these ways of creating gender from precarity, that we were able to grasp some of the radical → imagination and libidinal impulse that characterised them. In the year 2003, through crucial conceptualisation works such as Museo Travesti and Saturday Night Fever by Giuseppe Campuzano “Giu”, travesti bodies became visible as a disruptive force in the generation of normalities, an aesthetic metaphor and a symbol. Also the same year, the murder of eight travesti in Las Gardenias bar by the guerrilla group MRTA was registered in the Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación.[4] It was a historic but still limited gesture that acknowledged the hate element of the crime, but left the gender of the victims unrecognised, so their names were given as masculine in the book. But as fundamental as such events were to get closer to travesti lives, what still remains invisible is the complex weaving of relations of → care (→ care) in which through communitarian bonds an ethics started to develop and nourish today’s → LGBT+ and → feminist movements with new sets of tools. Those relations were deeply rooted, as I came to understand over months of listening to the testimonies of friends, allies and survivors, in a specific dimension of the body that had only been observed at this point of travesti memories (at least in Peru) with regard to negative impact. Vulnerability has mostly been considered as a ground that enables victimhood, but in the Virgen de la Puerta this inevitable human condition was so intensified by exclusion and many other forms of patriarchal and economic violence that it was turned by those trans and travesti women into the very foundation of an ethics of care in which their community development was grounded. Death, illness and hunger became nodes that were intertwined and dignified by a complex web of collaborations that assumed the processes of accompaniment, contention and both affective and economic support that the state and the biological family denied them. An ethics of → interdependency in the core of catastrophe, as my fellow colleagues in Reina Sofía Museum referred to the numerous autonomous neighbourhood actions that intervened in the social and economic crashes that occurred in Lavapiés neighbourhood, one that has some of the highest unemployment and migration rates in Madrid.

Those Latin-American, travesti memories of how vulnerability can spark desire instead of fear when it is inhabited communally are crucial for a Global North so constructed from safety narratives and promises of invulnerability, and the subjects that generate from it, all of them cracking and crumbling when faced with the materiality and interrelated character of an existence that was for so long neglected in favour of a supposed horizon of freedom without responsibility. The nature of this libidinal impulse has more to do with realism than with optimism, as Alba Rico noted in his wonderful article “Contra el optimismo”. To be able to acknowledge our own vulnerability in others, and others’ vulnerability in ourselves, the loss, mourning, and ruins, and still find the cracks in which to create the conditions for making the world liveable.[5]

In these lines of thought I’d like to address and hopefully reveal how all these territories and subjects built upon the fiction of individual freedom and self-sufficiency have a political responsibility, but also a chance to relieve themselves from that delusional and self-destructive point of reference, to withdraw by assuming vulnerability as a frame from which “to face with dignity and without cynicism the difficult times to come. Times that, by the way, started long time ago”[6], because lockdown, surveillance, the pandemic, and isolation have been familiar to the travesti and many others in recent times. I propose to engage in the communal inhabitation of vulnerability through memory in order to enable a wider, more inclusive → After. For that purpose, I will tackle what vulnerability means in the process of the reconstruction of the Virgen de la Puerta community through the dimensions of body, desire, time (After-life) and archive.

Body

Introducing my term and taking the cis-hetero European male as a starting point during the Subjectivisation II seminar was a deliberate → choice, as it is by far the subject that historically has been the most supported by the narratives of self-sufficiency that the pandemic has at least shaken. Who, to begin with, is this man? Is it the young Spanish migrant who delivers hamburgers at -15 Cº in Berlin? It is the medicalised academic on the verge of a mental breakdown? The single guy who saw his uncomplicated inability for commitment turn into an endless nightmare of isolation? During the long, cold and dark lockdown of Berlin it became clear that some had better chances to “escape” from the vulnerability of their bodies and minds than others. While most of the people performing cognitive jobs were frequently → travelling to Mallorca to take a break from the depressing landscape of home, the ones whose economic activities relied on the material force of their bodies couldn’t dare do the same. Cleaners, delivery drivers, caregivers, and so on stayed in this environment, stripped of all the things that make repetitive service work routines tolerable.

The first time I focused on working class masculinity and its relationship with embodied experience the young men interviewed considered themselves apolitical, showed extreme confidence and trusted in their own ability to face a world that didn’t seem to hold any uncertainties for them. The pandemic upset those frames of reference to a point in which it is possible to spot a late but rather abrupt loss of “innocence” and a fall into a type of embodied existence that had been only familiar to trans, → queer, migrants, imprisoned people and sometimes women. Interviewed again after the first lockdown those same men were quite different from their first testimonies. The narrative that prevails now is one of betrayal.

It is interesting how this concept also surfaced when I spoke about gender construction and affirmation with the Peruvian travesti women of Virgen de la Puerta. According to their testimonies, to embrace a position systematically made vulnerable, such as the feminine, having been “granted” the privilege of being born on the dominant side, was considered the ultimate betrayal that called for a cautionary punishment. It is not only that the → disidentification processes reveal the cultural and then questionable character of dominance in masculinity, but perhaps even more important the unveiling of the fragility that constitutes its embodied manifestation and that is perhaps preferable to address in different conditions and from a different set of values than those prevalent in male communities.

“Our bodies speak, tell stories,” Lalys said to me after recounting an exhaustive history of death, illness and transmisogynistic violence, from AIDS and experimental body modelling procedures to exclusion from health systems, and from hate crimes to torture and state terrorism. And it is precisely in that enunciative subject, the body, its fragile, ephemeral and vulnerable character, that a communal bond is generated, as Belisa added later: “We weren’t a community, but rather a fragmented and disperse numbers of individuals, but AIDS changed everything.” In the context of the total lack of health care given to the travesti community, embracing their vulnerability paradoxically became their basis to ethical and affective survival, although life became something perhaps different from what the capitalist, patriarchal and colonial narratives had built around the term, something that means a lot more than biological permanence and that happens in this existence and in the afterlife. During the seminar, the term “withdrawal” was also mentioned and briefly discussed and posed as an interpellation to all those subjects of dominance and self-sufficiency narratives, but I find the term “surrender” more expansive and richer in political possibilities because it breaks the tension and creates a digression that is not passive but an invitation to operate through a different form of interaction with norms and the sense of self and other. In the travesti world volleyball matches, for example, were spaces where this type of surrender opened a crack for a peripheral approach and sensibility towards beauty, joy or even survival. According to team names as outrageous as The Infected versus The Terminally Ill, the players were all already losers in the game of a normative life, only that they weren’t playing that game anymore. They were indeed sick and stigmatised, but above all they looked out for each other, they weren’t alone. The invitation to surrender I am posing here is aimed at the dimension of the self that is still in denial of its individual vulnerability and how it always depends on others.

“Life springs from the ultimate resignation”,[7] Polanyi said. Has this kind of sensibility been revealed to white European working class men since the re-acknowledgement of their embodied existence in which the lockdown pushed them? It would be too soon to know. But for them or any other subject or group of subjects that are willing to turn that sense of betrayal I referred to earlier into creative surrender, desire and hope, the register and exploration of the memories of the travesti community of Virgen de la Puerta aims to contribute to the collective navigation of that shift with an impressive set of ethical tools.

Motherhood

John Berger wrote that there is a big part of pain that cannot be shared. But the desire to share the pain can be shared. And from that action inevitably arises resistance. There are many threads that intertwine in those spaces of resistance, all of them come from a wound, a loss or an absence that is reshaped into contention and creates corridors of sense when shared. I´d like to focus on one that already emerged during our seminar, which is the conformation of support systems with an affective basis, and how they transform into a common politics that expands the notion of motherhood.

As expulsion from the biological family and the safety of the first home at an early age was and is still a common condition from which travesti women face the basic questions of life and death, the development of alternative bonds and spaces of care is crucial. → Mothers or Madres in the travesti vocabulary are experienced figures that have accomplished an aspirational gender construction or minimal financial stability. Both conditions work as shields that push transgender hate and violence, hunger and illness further away. So, travesti motherhood encompasses not only emotional support but also a pedagogical role that focuses fundamentally on the transmission of the skills of feminisation and becoming “streetwise, including the arts of sex work. Feminisation, especially extreme feminisation, was essential in patriarchal and transmisogynist environments: any feature that could disclose masculinity in a feminised body could lead to a hate crime, so the incorporation of feminisation strategies into the less experienced travesti subjectivities reduced danger considerably, giving instead a place for a chosen vulnerability that was collectively debated and built. Making one’s own kin might not be the same as biological survival, but it is definitely a way of transcending senseless material permanence.

The role of a mother could be ephemeral and multiple within the community. Some of the mothers took care of twenty girls and were also taken care of by them. Other mothers took care of a single young travesti girl all their lives, in every sense. But most remarkable, perhaps, many travesti women were mother figures to children outside the travesti community: the sons and daughters of neighbours, nephews and nieces, siblings, and so on.

Annie Bungeroth, photographer who recorded the daily lives of the girls intermittently for a period of five years, pointed out that the general conditions of the neighbourhood were marginal, to a point in where there was no place for internal fracture. This level of exposure to all forms of disaster made very clear that mutual support was the only non-self-destructive choice for the travesi to squeeze all possible well-being and value from their short life expectancies. This peculiar truce between prejudices in the middle of an ultra-conservative society gave shelter to some of the first travesti matriarchs and mothers, and gave them the chance to create their own spaces and reproduce the care that they had received by offering it to young, less experienced travesti girls not only from Lima, but from the whole country.

The women rented small rooms and shared bathrooms in old buildings that became travesti microcosmos, worked the streets during the night and participated very actively in the community, as noted before, both caring for others but also as devoted worshipers of the neighbourhood´s protector, the Virgen de la Puerta. After their daily errands and before heading to their street corners at night they gathered in Candy’s beauty salon to pray, attend informative workshops on STD prevention, fix their hair, nails, make up and spread the news about who was sick, who had not been eating and who had a problem with the police. Mothers usually stayed in the beauty salon performing as coordinators of all upcoming and corresponding actions. Taking into account how badly AIDS, tuberculosis and transmisogynist violence hit the collective, an important part of this news had to do with someone entering the terminal phase of a disease or being severely wounded.

Death, especially early death, was an inevitable dimension of the communal bonds in the Sebastian Barranca neighbourhood, and mutual care and attention became the strongest tool of the travesti to push it farther and expand the → territory of life, although not necessarily in its biological, individual sense. As much as collective action and social economies played a fundamental role in improving the conditions of the community, and NGO volunteers and LTGTB+ activists introduced tests, medicines and food donations, life expectancy still barely rose above 35, and thus a 45-year-old travesti woman would be considered to be in her third stage of life. What life came to mean in this community had more to do with a sense of dignity that evolves from the ability to be capable to give to others what you barely have, and the determination to create a world of value for bodies neglected, rejected and diminished in the world of patriarchal and capitalist norms. To express this in better words, I’d like to quote Santiago Alba Rico again:

Is this which unites, at an intersection of paradoxical contempt, capitalism and patriarchy: for capitalism devalues the worker who values all commodities and patriarchy devalues the worker who values all bodies. Therefore, if we want to preserve wealth and human dignity (whose source is a combination of work and time) we must wage a double and simultaneous fight in favour of economic independence and reciprocal dependence. How much is a human worth? The time we have worked on it. That’s what we call ‘love’.[8]

“After”-life

In the course of our Subjectivisation II seminar there were many moments in which I felt the need to re-think my take on “vulnerability” through the prism of my colleagues’ contributions. Although a particular term felt crucial for the sake of a wider, diachronic perspective. → After, as Jesús Carrillo pointed out, breaks the cycle of the perpetual present that “post-” ensured, “giving place to a different kind of play”. We won´t refer to such condition as “new”, avoiding not only the colonial implications and resonances of that term but also acknowledging that “after” was a pre-existing dimension of the future, crafted in the bodies and subjectivities that are persistently exposed to a sort of vulnerability that the “post” ensures to have overcome. “After” Carrillo continues, “was surely already in the hearts, imaginations and experience of migrants, refugees, of many women, youth, trans and queer people who were not allowed to have a proper life ‘yet’…”

The travesti and trans women of Virgen de la Puerta were certainly excluded from normal existence and not given the chance to enjoy this kind of life, so instead practised a form of re-existence based on the developing and sharing of the skills needed to face vulnerability communally. As noted before, death played a major role in these exchanges but was not by any means the most radical point of that condition. What happened “after” was instead, meaning not only the funeral services but also the preservation of the gender of the deceased in their bodies, epitaphs, headstones and memory. Body profanation of travesti and trans bodies was and still is a common practice, usually perpetrated by member of the biological family that didn´t accepted the transition of their relative. This manifested through the cutting of the hair and nails, dressing the body in a man’s suit and sometimes even the placement of a fake moustache. The travesti community turned the “end” element of death into an “After-life” by making sure not only that those bodies were kept feminine, but also remembered with their chosen names and nicknames.

The “After”-life became in this way in a space of care in which vulnerability was acknowledged and attended to through diverse means. To illustrate this point I’d like to refer to Jesús Carrillo’s contribution once again when he speaks about the “libidinal economies of the “after”. Sexual work and collective funding such as the popular polladas (parties funded with pre-sold tickets for a meal of grilled chicken and beer) played an important part in the composition of economic ephemeral structures. Regarding sex work, those commitments were cross-border, due to the constant flow of migration of travesti and trans women from Peru to countries such as Italy (principally), France, Germany and Spain. Of course, polladas moved a modest amount of cash that contributed enough to cover the burials, while sex work funded gender reassignment, activism, house building, other migration processes and advanced studies. The conditions of vulnerability within which migrant travesti sex workers survived in and from Europe are yet to be adequately incorporated in my research, but the fundamental role of migrant money and how it found and gave life in such neglected territories needs to be emphasised.

In the Virgen de la Puerta community, the “After”-life was the space in which the feminine name that was forbidden in regular life met time, future and memory, implying that the deceased did not become foreigners to the communitarian exchanges and responsibilities that took place there and that those still alive recognised themselves in them. For that, not even those thrown into the ultimate “after” were left behind – on the contrary, that’s where the truncated pasts of travesti and trans women were restored to posterity.

Archive

How do we collect and organise truncated pasts? How can we narrate vulnerability not only from a content perspective but acknowledge it in the format of discussion and activation? As the archive we are developing is taking the form of a podcast, the question of working with sound holds implications that encompass space and time. Space is a decentred form of inhabiting something that allows the vulnerable regions to activate in such a manner that evokes a sense of interwoven permanence and loss similar to the kind that can be found in the presence of ruins. The idea is to pursue the creation of places for a conspiracy “where whispers are audible”, as Jesús Carrillo has invited us to do. This means we consider gaps and empty spots as territories too. Do they mean abandonment or just secrecy? What does the impossibility or the difficulty of exploring them tell us about the environment where they’re located? In them, tiny traces of desire or mourning that transcended don’t compete for attention, they just become visible like ghosts do, for those who are willing to see them.

We tried to keep some distance from the digital logic of false fidelity and the erasure of pauses, and instead searched for resources that allowed us to expose the fragile, ephemeral and unstable quality, not only of the memories being recorded, but also of the subject itself. Our goal was to create the atmosphere of a séance, in which just as pauses were vindicated, so silence, repetition, loops, echoes, delays and other forms of de-structuralisation and re-structuralisation of sound became a language for re-existence. Our role, both researching and crafting the format of the sound archive, became similar to that of a medium.

No territory has so many disappeared socialists and activists as Latin America, → the dead whose mourning does not end and has not even begun. The historian José Carlos Agüero asks himself if bodies in the context of memory, violence and the process of being made vulnerable are just remains, relics, or something central that we should reflect on.[9] The question is how to approach such vulnerable matter as these violated, reduced and marginalised bodies that manifest almost as exhalations or pieces of memorabilia. For us, ghosts are definitely subjects and, as they inhabit in the dislocations of time, the space we generate for them to be hosted in the sound archive was conceived within those parameters.

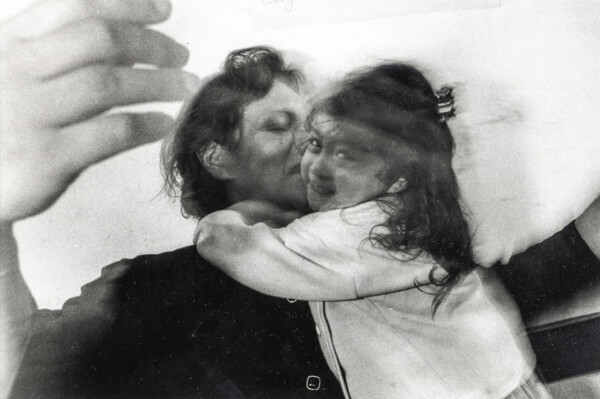

The visual aspect of our research on the travesti community of Virgen de la Puerta was based on a series of images captured by photographer Annie Bungeroth intermittently over a period of five years. The relationship between Bungeroth and the travesti women of the neighbourhood started with an encounter with Lorena “La Piurana”, an iconic character in the artist’s photographs and a central figure in Giuseppe’s Campuzano Museo Travesti counter-narrative project. In our case, we have chosen a picture of Lorena with Alejandra, the little girl she babysits and who called her mother. (Figure 1) In the photo Lorena has her arms wide open, so open that is almost like she is also embracing the photographer and the person who is looking at the picture, or rather – the future. Her eyes are closed. The girl is clinging to her neck, smiling at the camera. The caption is the visual definition of openness, of letting oneself be vulnerable and at the same time protective, which is in fact the core theme of the entire Virgen de la Puerta community, a fragile but still effective balance between acceptance, negotiation and struggle.

Figure 1: Annie Bungeroth, “Lorena ‘La Piurana’ with Alejandra”, photograph, La Virgen de la Puerta series, mid-1990s. Courtesy of the artist.

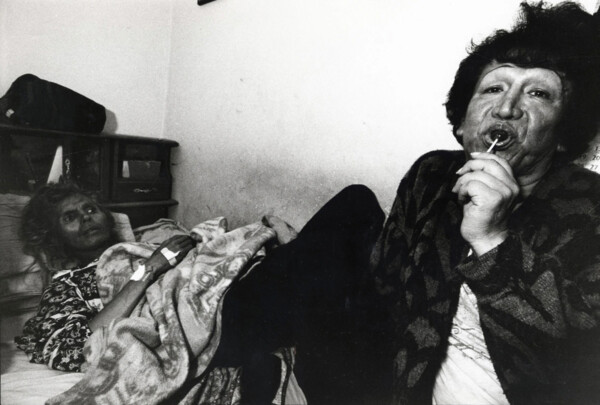

The rest of the visual corpus that Annie built is a diverse mix that represents everyday life in the Sebastian Barranca neighbourhood, from the community’s regular prayer gatherings and devotional ceremonies and processions, to celebration, migration and grooming rituals. AIDS and suffering are a major and important part of this archive, specially from the point of view of those being photographed. One of the things that Annie insisted on was the way Lorena, Candy, Cheyla, La Chunga and the others perceived the documentation process as their most important achievement, in times of illness and death, particularly. In fact, Annie was one of the first people who were called every time a girl entered a terminal phase of their condition. There is a specific image in which La Chunga is sucking a lollipop, sitting next to a dying woman with catheters in her arm. (Figure 2) For them, to know that such losses and pain were being followed and captured meant also a step into the “After”-life and beyond death. Even if the bodies were impossible to recover, there was proof that they didn’t die alone or abandoned, that they were poor and hopeless but still had the ability to be kind, generous, and engaged.

Figure 2: Annie Bungeroth, “La Chunga with a Lollipop and a Dying Woman”, photograph, La Virgen de la Puerta series, mid-1990s. Courtesy of the artist.

Every year that Annie went back to Peru and to the neighbourhood of Sebastian Barranca, another girl had been murdered or entered the final stages of AIDS or tuberculosis so her original plan to film a documentary became less and less plausible, until the death of Lorena in which everything about the original plan became more or less pointless. They had become such good friends. Lorena cared for Annie’s vulnerability, as a white European woman in one of the most dangerous neighbourhoods of Peru, and Annie, as she says, saved Lorena’s teeth by convincing her to stop using them as bottle openers. Lorena had told Annie that the documentary would be the most important thing that she would do in her life, so we tried to do justice to this. She is the guardian angel and patrona of our research, and for her example, inspiration and legacy of resistance in tenderness and care we are truly and forever thankful.

Is it possible then to rebuild a subject conceived in a systemic condition of vulnerability and erasure? We think not. The bodies don’t come back, and we decided not to hide this impossibility and instead generate a tool that zooms into the mechanisms that intervene in our present relations to make them so violent, and an instrument that works at the same time as a compendium of strategies and resources conceived in such conditions of fragility to show that even when a → repair is not possible there is a chance to improve the present.

If we succeeded in fulfilling these expectations then we’d be also reflecting on the vulnerability of memory and the insufficiency of the archive itself, its romanticisation and asymmetricities involved in the collective → process of mediation between the experience of the other and what matters to the researcher, and also that deficiency, that limitation shouldn’t be hidden either. On the contrary, it should be noted that our role as mediums is exposed as failed. As Susan Sontag said: “Perhaps too much value is assigned to memory, not enough to thinking. Remembering is an ethical act, has ethical value in and of itself. […] To make peace is to forget. To reconcile, it is necessary that memory be faulty and limited.”[10]

![Subjectivisation 2 [Final discussion]](/website/var/tmp/image-thumbnails/0/1478/thumb__logo/Mick-final-discussion.png)