Empathy is often defined as the capacity of understanding, being aware of, sensitive to, and experiencing the feelings of another.[1] However, a very complex notion of empathy has evolved in the context of the humanities and cognitive neuroscience since the term was coined in the 19th century by the German philosopher Rudolf Lotze as a → translation of Greek empatheia, “passion, state of emotion”. Empathy is often perceived as a positive feeling. However, a number of critical theory studies have raised the issue of the ambiguous impact of empathetic emotions on our happiness.

“I feel you” but “I don’t feel with you”

The notion of empathy sits at the heart of theatre, the performing arts, and empathetic pedagogies. In literary theory there exists the notion of “narrative empathy” as the sharing of feelings and perspective induced by reading, viewing, hearing, or imagining narratives of another’s situation and condition – i.e. “being in the shoes of” fictional characters. Empathy is also broadly discussed as part of affect studies and feeling theory. Distinct types of empathetic thinking have appeared in the visual arts context, especially in transdisciplinary and narrative practices involving different methodologies of working with humans, non-humans, objects, and narrative fiction, as well as in the critical discourses of → feminism, postcolonial, and → queer theory.

At the beginning of her essay “Empathy”, Beverly Weber asks:

Can you ever feel me? Can I ever feel you? What is this feeling, and what alliances might it motivate? Can empathy play a role in decolonised solidarities? Does it rely on shared → vulnerability? To whom do we feel obligation? To what extent? In what way does that sense of ethical obligation rely on empathy? How does empathy function as an emotional force that compels one to move?[2]

In her work, Weber quotes Sara Ahmed’s Becoming Unsympathetic essay, which refers to the idea of sympathy.[3] Although sympathy is related to empathy, it has a different meaning. Sympathetic concern is driven by a switch in viewpoint from a personal perspective to that of another group or individual who is in need. Thus, the expression of sympathy could be phrased as “I feel you” but “I don’t feel with you”.

How do things become emotional?

One of the definitions of empathy refers to the “imaginative projection of a subjective state into an object so that the object appears to be infused with it”.[4] After Sara Ahmed, we ask how do things become emotional, or after Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick: how can we touch them? Amelia Jones, in her essay Performing the Wounded Body: Pain, Affect and the Radical Relationality of Meaning, reflects on the authenticity of emotions and affect evoking a question of affected experience mediated through artistic means:

In Derek Jarman’s 1986 movie Caravaggio the artist says to his friend, ‘[i]n the wound, the question is answered. All art is against lived experience. How can you compare flesh and blood with oil and ground pigment?’ In a telescoping set of identifications, Jarman, via an actor playing the artist Caravaggio, begs the question of the effect of the wound as felt, enacted and represented visually: is a ‘live’ wound inherently more authentic than one made ‘with oil and ground pigment’ or, for that matter, with photographic media? And, in relation to these registers of mediation, what does the wound mean as a cultural signifier: one presented to another in a moment of communicative exchange?

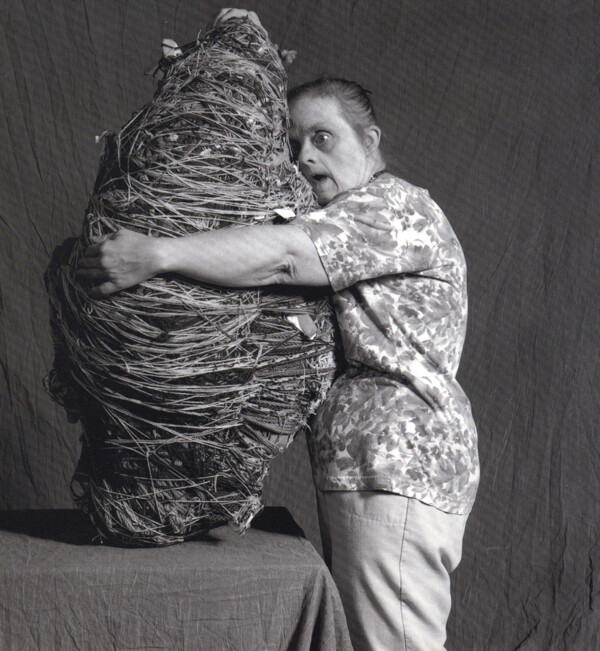

The examination of empathetic objects and images can relate to the sculptural works and further to the truly extraordinary photographic portrait of Judith Scott (1943–2015) with one of her objects, which was taken by the photographer Leon A. Borensztein. (Figure 44) This is how Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick describes this image in her book Touching Feelings:

The sculpture in this picture is fairly characteristic of Scott’s work in its construction: a core assembled from large, heterogeneous materials has been hidden under many wrapped or darned layers of multicolored yarn, cord, ribbon, rope, and other fiber, producing a durable three-dimensional shape, usually oriented along a single axis of length, whose curves and planes are biomorphically resonant and whose scale bears comparison to Scott’s own body. The formal achievements that are consistent in her art include her inventive techniques for securing the giant bundles, her subtle building and modulation of complex three-dimensional lines and curves, and her startlingly original use of color, whether bright or muted, which can stretch across a plane, simmer deeply through the multilayered wrapping, or drizzle graphically along an emphatic suture. All of Scott’s work that I’ve seen on its own has an intense presence, but the subject of this photograph also includes her relation to her completed work, and presumptively also the viewer’s relation to the sight of that dyad. For me, to experience a subject-object distance from this image is no more plausible than to envision such a relation between Scott and her work. She and her creation here present themselves to one another with equally expansive welcome.[5]

Figure 1: Leon A. Borensztein, Judith, 1999, photograph. Judith Scott hugging her cocoon sculpture.

Judith Scott was born with Down’s syndrome in Ohio, the United States. Additionally, her deafness was undetected for years, causing learning difficulties and exclusion, which led to her being sent to an institution for disabled children. She spent 35 years separated from her family, until 1986, when her twin sister became her legal guardian and moved her to her home in California. Judith Scott then joined the artists’ studio of the Creative Growth Art Center in Oakland, where, after two years, she began to produce unique sculptures by collecting various objects of all sizes and shapes, that she wrapped, wove, and entwined with threads, in carefully chosen colours, day after day, sometimes for months, until forming strange cocoons hiding talismans known only to her.

Scott’s mysterious and powerful sculptures recall the concept of Sara Ahmed’s affect as something that’s sticky: “Affect is what sticks, or what sustains or preserves the connection between ideas, values, and objects.”[6] Through these objects, Scott developed her own abstract language as the only connection between inside and outside world. The Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory refers to the physical sensation when we speak about empathy as follows:

When we experience empathy we identify ourselves, up to the point with an animate or inanimate object. One might even go so far as to say that the experience is an involuntary projection of ourselves into an object. This complementation of a work of sculpture might give a physical sensation similar to that suggested by the work.[7]

To be empathetic is to suffer

The case of Judith Scott’s sculptures proves the ability of art to function as means to facilitate empathy. Sculpture can be used as a vehicle for feelings and emotions, and help us to imagine an experience. Empathy is also all about the → imagination, since you can’t really be in the shoes of someone else. Moreover, empathy is a powerful tool, and we cannot survive as a society without it. Consequently, it is hard to imagine the development of art or critical discourse without empathy, and we shouldn't forget what Sara Ahmed says in her book The Promise of Happiness:

To be empathetic is to suffer: it is to be made unhappy by other people’s unhappiness. It is not necessarily that you catch their feeling but that you have to live with their unhappiness with your life → choices (“ideas about structures”). Such unhappiness is directed toward those who do not live according to the right ideas. They are unhappy with you for not being what they want you to be.[8]

![Subjectivisation 2 [Final discussion]](/website/var/tmp/image-thumbnails/0/1478/thumb__logo/Mick-final-discussion.png)