Faced with terror, fear, oppression, lies and extermination, can one give oneself the right to – more than being speechless – remain in silent? After all, it “feels like we should be outside hunting for snakes, biting on knives, kicking on doors”, writes Mercedes Villalba in her Fervent Manifesto.[1] Silence gives consent, claims the old saying. Silence will not protect us, Audre Lorde constantly remind us.[2] How dare we choose to remain silent? How can we not want to make ourselves heard?

“What’s in your mind?”, Facebook asks me. “What’s happening?”, Twitter asks me. “Ask me a question”, Instagram asks me to ask.

“Hello! I know that you are here, listening to me”, says Mayor Tony Junior when he arrives in Bacurau, a rural settlement located in the state of Pernambuco, in the northeast area of Brazil. Seeking to attract more votes for his long-awaited re-election, this cynical and colonialist politician pays a visit to this impoverished village. Loud electronic music and huge LED screens installed in trucks serve as a background for his performance, in which he → reclaims, with an intentionally kind voice tone, the physical presence of the inhabitants in the central dirt street. But despite the spectacle of his arrival, this man receives back their silence and invisibility. Promptly Bacurau’s people decide to hide inside their houses and, by doing this, disarticulate any possibility of conversation. “I know that we already had our differences, but today, I am here with my open heart”, the mayor insincerely appeals to a sense of concord.

Bacurau is also the title of the internationally praised Brazilian movie directed in 2019 by Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles, in which this disquieting encounter takes place. Even fictionally detached from the current pandemics, but installed in a comparable dystopian situation, it seems that Bacurau’s people strategically decided to #stayhome, instead of exposing themselves to a literally deadly contact with power.[3] Because, perhaps, in the face of power, as María Galindo states, you do not empower yourself, but rather, you rebel against it.[4] And somehow, in this silent and apparently apathetic strategy, they found an unexpectedly radical form of opposition. Why not incarnate the very meaning of the word bacurau – the wild bird that only flies at night and camouflages itself among the dry leaves on the ground – to put into practice survival techniques and subjectivisation processes based on more discrete and minimum procedures? Why not disengage certain interchanges, get around other’s wills for conflict, be voluntarily non-available, non-readable, non-responsive and choose to exist on a different frequency?

“Hey, let’s go, come here, come out. Please, let’s talk”, begs Tony Jr, once more. Unsuccessfully.

To come out

“To come out” means, in English speaking → queer jargon, a speech act of self-disclosure of one’s sexual orientation and/or gender identity, and, in the most cases, operates as a form of confronting the oppression, shame and social stigma. “Out of the closet, into the streets!” was an early North American gay activist slogan, chronologically followed by others like “We’re here, we’re queer. Get used to it!”. I myself, while writing these lines, can see a poster hanging on my wall that defiantly celebrates: “Still here, still flamboyantly queer.”

Out, loud, and proud: the possibility of queer existence and resistance being intimately dependent on a queer discursiveness, presence, and visibility is also structural to the historic motto of Act Up’s demonstrations: “SILENCE=DEATH”. Becoming the central visual symbol of AIDS activism, this slogan, printed in white letters on a black background alongside the pink triangle that critically refers to the Nazi persecution of LGBTQIA+ individuals, sums up the urgency of those times.[5] Times of resistance that, maybe more than ever before, we all agreed – with rage, mourning, joy, pride, and pedagogical impetus – that silence wouldn’t (and didn’t) save anyone.[6]

But some miles away from the streets of cities like New York, Paris, Berlin, and Barcelona, a less known HIV+ artist based in São Paulo, José Leonilson (1957–1993) may have been publicly addressing another possibility “to act up, fight back, fight AIDS”[7]: Não ouço, não vejo, não falo. [I can’t hear, I can’t see, I can’t speak.] This fragile yet disquieting drawing produced some weeks before his death from AIDS-related illnesses is one of his last contributions as the official illustrator of “Talk of the Town” column written by the journalist Bárbara Gancia in the most read Brazilian newspaper, A Folha de S. Paulo[8]. Apart from the possible connections with the popular Japanese legend of the “Three Wise Monkeys” and some Zen-Buddhist interpretations, and far from being a hopeless self-portrait of a sick young gay man condemned to a lonely and stigmatised death, in this drawing Leonilson displays a very personal approach to his fight as an HIV+ person, disturbing any protest guidebook devoted exclusively to more loquacious forms of activism.

By no longer holding his longed “citizenship of the kingdom of the well” – quoting Susan Sontag in her essay Illness and its metaphors[9] – he had to forcibly withdraw from the frenetic game of exchanges and fluxes promised by the neoliberal illusion, for example, the idea of a planetary space without borders, totally open and fluid. Following Lina Meruane’s historical analysis in Viral Voyages: Tracing AIDS in Latin America, this artist might be considered as part of what she describes as a dispersed global community, constituted by young homosexual cis-men who, for a quiet brief moment during the 20th century, embodied an ideal avatar of the capitalist culture: smart, free and individualist bodies, full of desires, with exquisite tastes and daring opinions. With the HIV/AIDS epidemic, what was once seen as their enviable freedom was reframed as a suspicious loneliness. Those wandering bodies, so difficult to halt, came to be feared for their high danger. Those expansive men turned to be the perfect metaphor for that frightening virus that they carried in their own bodies.[10]

In his turn, Leonilson – exiled in himself, who “does not see, does not hear and does not speak” – seems to find his condition of existence in a profound impenetrability, in all possible meanings of the term something that, in this world obsessed with movement and interaction, is no less equivalent to be a subject in the verge of disappearing, being completely muted, “cancelled”. However, from his apparent condition of a lack of power, he ends up confronting us with an unexpected perspective with which he observes and comments on the world. A world that keeps granting itself the right to immobilise him in pathological categories. In this way, when he suggests graphically he hears nothing, speaks nothing, and sees nothing, he is actually building up his most demolishing poetics: wouldn't Leonilson be intentionally occupying the media arena with his caustic “silence” to paradoxically, effectively convey discourses potentially ignored by public opinion? Moreover, couldn’t this drawing be a depiction of a specific survival knowledge conceived by many minoritarian subjectivities, that find in the act of blocking the channels from which the systemic violence invades our bodies, our decisions, our → imaginations, and our right to intimacy, a way to enhance other senses to live not despite, not against, but beyond?

Thus Leonilson’s unexpected way to gain, save and then unleash power by strategically “disempowering” and “silencing” himself may not fit perfectly into the notion of “activism” conceived by early AIDS activists. However, this same “silence” may lead us back to another Act Up’s tactical lexicon: the “die-ins” – protest happenings where large groups of people lay down in a public space, feigning death. “The strongest thing we can do is something in silence” declared the activist Robert Hilferty, when recalling the preparation for the highly publicised die-in at New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral in December 1989.[11] As Roi Wagner notes, “performing an object position to apply force is a marginal stance that may be a last resort for those who have little to lose.”[12] To be inert, to remain silent, to choose not to react to other’s actions, is anything but a refusal to participate in the public debate, nor an inability to join it, but, potentially, a way to subvert its terms.

Being in silence does not mean to have been silenced. And, sometimes, even laying down in silence does not mean a performative gesture with political outcomes, but a condition of participation for other political subjects. This is the case of Johanna Hedva, author of the Sick Woman Theory, for whom most modes of “political protest are internalised, lived, embodied, suffering, and no doubt invisible”. During a Black Lives Matter protest – which she would have attended, had she been able to – she remembered listening to the sounds of the marches as they approached her window. Stuck in the bed, in silence, she rose up her sick woman’s fist in → solidarity, “thinking of all the other invisible bodies, → with their fists up, tucked away and out of sight”.[13]

“Please, let’s talk”, insists Mayor Tony Jr.

But, with whom we are supposed to talk?

Fazer a egípcia

Fazer a egipcia means literally “to do the female Egyptian” in Pajubá. Pajubá is a sort of coded, encrypted, surviving language constituted by words and expressions coming from different African languages within the Brazilian Portuguese, spoken by both practitioners of different Afro-Brazilian religions – to avoid the religious repression – and by the Brazilian → queer communities since the military dictatorship period. This is an increasingly popular language that in itself, as Victor Heringer observes, carries some evidence of the social inclusion of its speakers in the Brazilian society, but, as a dissident language that forcibly resists the power, begins to die when approaches it. In this case, being broadly spoken gives room to be gradually silenced.[14]

It is true that, at a first glance, “to do the female Egyptian” may sound like an orientalist bad joke – being queer doesn’t prevent you to be racially biased[15]. But fazer a egipcia, as an expression used by any subjectivity historically attacked in Brazil, turns to be a recognition of silence as an admirable survival tool, since this embodies a complex set of sophisticated nano-actions. Because, ultimately, fazer a egípcia means to not give importance to a threat, to take distance from someone or some undesirable clash, acting with indifference and with a certain attitude of distance, impassiveness, and dignity, and, in a sort of a performative and silent gesture – physically incorporating the luxurious ancient Egyptian iconography – glamorously, look the other way.

“Learn to be quiet just as you learn to talk, because if talking guides you, being quiet protects you”, teaches the philosophy of Abu adh-Dhiyal, quoted by Hamsa Ahsan in Shy Radicals.[16] In this sense, this refusal to respond to the oppressor is more than a mere act of individual resistance. As the Pajubá itself, being silent by “doing the female Egyptian” works as a community-making tool, sustained by a healing trust and a self-preservationist shared secret. As Mercedes Villalba envisions, using the metaphors of the slow and almost undecipherable fermentation process, we should craft and inhabit pockets of air, hidden spaces, bubbles. But ones that rise up in fervour – even if they are temporary – where to go for nourishment or rest and, then, be ready to fight, and conspire, for our right to the future. Just like the bird bacurau over the night, the people of Bacurau inside their homes, Leonilson and Johanna Hedva in their beds, and the self-generated idiomatic realms we inhabit to both talk about the silence and live freely in it, “we will crawl and stay still for as long as we wish, expanding our presence”, Villalba envisages.[17]

Pockets of air: in a present so suffocating, all of this may sound naive, cowardly, and politically regressive. But now, as witnesses of another pandemic – on which, like the HIV/Aids crisis, in no case proved to be exclusively a sanitary one – we are keenly aware not only of the medical implications but, above all, the healing power and political scope of “us breathing together” – the very etymological origin of the verb “to conspire”.[18] Still with that vociferous “I CAN’T BREATHE” resonating in our ears, it is evident that our breath – that is to say, our capacity to be in silence and just exist within our multilayered, diverse, and unfixed splendour – is the ultimate → territory from which the oppressive forces aim to evict us.

“Please, let’s talk”, repeats Tony Junior.

But, talk about what?

In a recently published short story, Jota Mombaça poses the question: “Why bother formulating a mode of saying or showing, if we could express and share things that words and images couldn’t even begin to articulate?”[19]

How can I express myself without letting my acts and opinions be co-opted by the logic of hyper-productivity, self-exploitation, mandatory visibility, and the “universal” intelligibility?

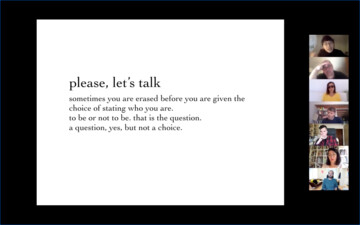

Ocean Vuong brilliantly notes in On Earth We Are Briefly Gorgeous that “sometimes you are erased before you are given the choice of stating who you are. To be or not to be. That is the question. A question, yes, but not a → choice.”[20] This is an epistolary novel whose narrator, a racialised and queer English-speaking young man, writes letters to his illiterate Vietnamese immigrant → mother, in a poetic attempt to fill the generational and diasporic silence between them, as when he states on the first page: “I am writing to reach you – even if each word I put down is one word further from where you are.” Escaping binary logic, this piece stresses that the so-called “subalternity” is never an easily homogenised category and that, within the opacity, there are invisible and countless ways of surviving systemic violence and the curse of not being heard.

The thing is: stating who you are is often an unpleasant and traumatic experience. Reni Eddo-Lodge, the author of a book that carries the self-explanatory title Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race, opted for disengagement and silence – at least when she sees herself surrounded by a vast majority that denies the existence of structural racism and its symptoms – since, in her words, “this is a game to some people and, if it is, I don’t want to play”.[21] She argues in a widely shared blogpost that eventually gave her the opportunity to publish a best-selling book, that “their intent is often not to listen or learn, but to exert their power, to prove me wrong, to emotionally drain me, and to rebalance the status quo. I’m not talking to white people about race unless I absolutely have to.”[22] A position aligned with what Julia Suárez-Krabbe suggests in her article “Can Europeans be Rational?”[23]: to deny interlocution when it is confined within an oppressive epistemology that inevitably transforms any attempt of answering into a violent experience of having to survive, bodily, discursively, and epistemologically, in the constrained realm of the oppressor’s verbalism. In short, as pointed by Raquel Lima, it is about time to understand that the subaltern agency is not a voice that only seeks a dialogue with the dominant narrative.[24]

Indeed, we are really tired of talking. “I'm not terribly angry, though I am that too: I'm up to the hell of the ‘trans’”, provokes Elizabeth Duval in the first page of Después de lo trans, in which she advocates, as a trans writer, her right to not talk about what others supposedly expect to hear from her: “I write this book so that, finally, you will never ask me again, reader, neither you nor anyone like you, about trans, about the conception of trans, about a thousand debates that do not interest me. I write it so that I can later write freely from what I do want to write about. Hopefully, I can: then I can say that the same text that defines my condemnation is the one that gives me freedom. And I will return, finally, to write for, to, and looking for pleasure.”[25]

In fact, Glissant has already claimed the right to opacity for everyone and freed us from the oppressive duty to be totally understandable, perfectly knowable.[26] He opened possibilities for us to obliterate the dominant logic that insists on forcing us to clearly answer its questions, satisfy its data demands, and, consequently, optimising its mechanism and extending its validity and reach. A resembling logic seems to be reinforced in 2019 by the rapper Emicida, when he rhymes alongside the queer pop stars Pabllo Vittar and Majur:

Permita que eu fale, não as minhas cicatrises

Achar que essas mazelas me definem é o pior dos crimes

É dar o troféu pro nosso algoz e fazer nóiz sumir

[Let me speak, but not my scars

When you think that these misfortunes define me is the worst of crimes]

It is giving the trophy to our executioner and make us disappear][27]

It is true that, “we need to respond to the systems that the political forces subject us to”, says Cinthia Guedes, “but also respond to ourselves, in a low voice and with great → care (→ care): after all, how will we go on?”[28] Certainly, I am not the one to judge the several and necessary forms of public, passionate and eloquent demonstrations. Nor do I intend to encourage an individualist, nihilist and uncommitted attitude. Rather, without any silly intention to establish a clear-cut and programmatic agenda – what a dull contradiction it would be to start establishing universal norms on how to generate political participation and materialising solidarity! – I prefer to imagine another path where we can continue “measuring the silences”, as proposed by Spivak,[29] to intelligently overcome binary constraints between activity/passivity, individual/collective, useful/useless, and life/death. After all, by choosing to be silent, we end up raising an exciting and uneasy moral problem. In this sense, as Nicolás Cuello puts it, there is “nothing better than shaking up the zombie agreement of progressivism.”[30] Rather than being haunted by white zombies, there is nothing better than to do the female Egyptian and, amidst empires and plagues, glamorously look the other way, speaking with the eyes like a poet who, as Paulo Leminski, whispers: “I say more and more the silences of the future.”[31]

![Subjectivisation 2 [Discussion #2]](/website/var/tmp/image-thumbnails/0/1476/thumb__logo/Discussion-2.png)

![Subjectivisation 2 [Final discussion]](/website/var/tmp/image-thumbnails/0/1478/thumb__logo/Mick-final-discussion.png)