Constituencies: Between ñande and ore

It is not a revelation that museums have to manage relationships with communities. The question could be formulated like this: Which community? Just as identity has become pluralised, so has community. Museums are inscribed in a community, which is usually plural. To whom are the museums and art galleries owed? Each institution has generated its own objectives as a function of concrete → interests to objects of study or incidence perspectives, work modalities, and, more specifically, according to its understanding of its own place of inscription or enunciation. The community in which a museum its inscribed – or attempts to – is far from being homogeneous. Very often the community is read as a conglomerate of those people that are part of a city, a neighbourhood, etc. The work is done “for” the community, as if the people who work or manage a museum are not part of any specific community.

Then, who forms that community to which the museum is owned?

In order to attempt an answer, I bring up two words in Guarani: the binomial ñande/ore, equivalent to the third person plural. Firstly, I will make a brief introduction to the concept and then relate it to a specific case: the Museo del Barro and the Seminar Espacio/Crítica, both dependants of the Museum itself. This relation would throw off some triggers that may be useful in understanding the idea of constituencies from another point of view.

In Guarani[1], the language spoken by the majority of the Paraguayan population, there are two different words for the first-person plural: ñande, an inclusive we, and ore, an exclusive one. That is: ñande includes the recipient, ore, excludes her.

Since the beginning, starting from language itself, “we” does not have a totalising or homogenising status. In Guarani culture, and by extension, the culture of Paraguay, different records exist to name ourselves and therefore for us to become community, society, citizenry. These two versions of “we” configure, somehow and on the basis of language, a different way of understanding identities.

This differentiation between the “we” that includes and that which excludes occurs only within the relationship between the speaker and the recipient of the statement. The person who speaks and names herself along with others will include or exclude said recipient following the demarcation she sets, and will change when the recipient or her function within the statement changes.

This idea of a “we” with porous borders, that is modified according to the idea of belonging or not belonging to a social or cultural group, is one that may serve the purpose of thinking about new ways of conceiving institutions, of thinking about otherness, of constructing citizenship.

From ore to ñande

When Carlos Colombino – one the founders of the Museum – affirmed that there was a need to create the Museo del Barro in order to live in Paraguay, I do not think he was exaggerating. It was the year 1972, and a group of artists in Asuncion, the small capital of Paraguay, felt they did not have space. Paraguay was immersed in Alfredo Stroessner’s dictatorship, and from 1954 to 1989 he ruled the country in the longest dictatorship in Latin America’s modern history. The records of the Museo del Barro and, later, the Museum itself, were born out of need. A need that responded, in its time, to a bounded collective. This collective would bring forward two issues (that were being brewed in other spaces): on the one hand, the issue of dispute for meaning – in a local scene, in which the traditional instances of representation were in crisis – and on the other hand, the explicit debate about unwritten cultures.

Artists and intellectuals that were involved in the creation of this space lacked asylum. Paraguayan institutions dedicated to art were co-opted; some of them were a faithful reflection of the political situation: Stroessner’s dictatorship; others were merely ultra-conservative, taking no political position at all. Being a rather small environment, the Asuncion art scene lacked alternative spaces that could answer to diverse subjectivities. The commitment of some artists to certain political positions prevented them from joining other movements that emerged between the 1950s and 1960s. These artists not only began to take other positions with regard to art, but other political positions altogether.

This small group of artists constituted itself as a community. Perhaps what some time later, Gustavo Buntinx called a community of meaning. That community broke through and let in other subjectivities that were also outside the official narrative.

Introduction to a brief story: The Centro de Artes Visuales/Museo del Barro, or the manifestation of difference

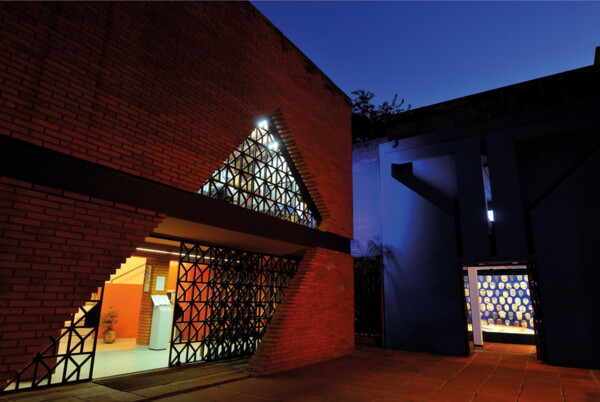

Figure 1: Museo del Barro, Main Entrance, 2015. Photo: Fernando Allen.

Figure 2: Museo del Barro, collection display, exhibition view, 2015.

The Museo del Barro came into being through several initiatives over the course of forty years. (Figure 1) What makes it unusual is that it has been created by artists, anthropologists and art critics. Originally, it emerged as a project that would function on the margins of the state and in opposition to its politics. The Centre’s three museums sprang into life independently. However, they eventually came together under one roof as one project. The Centre’s roots go back to 1972 with a Circulating Collection started by Paraguayan artists Olga Blinder and Carlos Colombino. The collection did not have its own space and moved from one place to another. In 1980, a permanent space for the collection was sought, with the Museo del Barro inaugurated in a small house. Osvaldo Salerno and Ysanne Gayet, along with Carlos Colombino worked in this project. Ticio Escobar later also join the group. The treatment of works in this museum makes it possible for popular and indigenous art to be seen as equal to urban or “erudite” art. The museum seeks to provide a dialogue between these types of art in spite of their differences, striving to undermine the official myth that popular and indigenous art can be reduced to “folkloric”, “authentic”, “vernacular”, “our very own”. That is, popular art can often be trivialised, stripped of its subtleties and differences. (Figure 2)

When Ticio Escobar – who has deeply reflected on Paraguayan art from this triple perspective in a systematic way – wrote La Belleza de los Otros (1994), he recounted the foundational story set out in El brazalete de Túkule. Túkule, a powerful Ishir shaman, is delicately making a bracelet. Escobar asks why it is necessary to add a line of multi-coloured feathers to something which appears to have already been finished, and he receives this answer: “So that it looks more beautiful.” This bracelet is functional – ceremonial, shamanic and ritual – but at the same time, it is aesthetic: it should attract our attention through its shining beauty.

The language of difference emerged intuitively at the beginning. First came practice and then theory; the Museo del Barro followed a path that revealed itself in the middle of the journey. It went about → constructing itself in fragments from total chance until it gelled (although it never completely did so) in one place (actually in two – that of the physical place and its conceptual place).

Figure 3: Museo del Barro, collection display, exhibition view, 2015.

Paraguayan art finds in the Museo del Barro a space in which we can see ourselves from multiple perspectives, talking to that “we” which in Paraguay means we are two (or at least two, since language always puts that duality in evidence). The idea of setting up a dialogue and bringing together the artistic productions of Paraguay’s different peoples came about through an unplanned action. This concept of art, that includes other ways to understand it set forth by Escobar and, by extension, by the Museum – the manipulation of material forms that shake up the senses. This very concept allows for the insertion of popular art into the writing of another history of art and to begin to dislocate Eurocentric concepts. (Figure 3)

The Museo del Barro significantly adopted the praxis of exhibiting texts, the theoretical basis that ties together questions that have arisen through doing. The Museum immerses the visitor in a collection of images and objects, often in a somewhat disordered fashion, not all categorised or classified in the way such institutions tend to present them. It houses collections of popular art and the art of different indigenous communities, as well as several expressions of the Urban-erudit Art of Paraguay and Ibero-America. It seeks to erase the distinct ways of classifying art, doing away with the boundaries between the popular, indigenous and urban in Paraguay. Thus, the Museo del Barro preserves the ambiguity of being a museum without totally being a museum. It attempts to skirt the boundaries of the concept of a museum while at the same time renders this concept, ill-fitting and permeable.

The Museo del Barro, with every action it has undertaken – often outside the scope of what is considered usual for a museum – has tried to make more malleable the borders of certain academic categories. Following this model, it finds other ways of involving itself into the world. The postulation of indigenous and popular art comes from this ability to make borders between different types of art more flexible. It looks to shake up the certainty of fields of knowledge; to move apparently fixed concepts so that we can observe that reality moves, letting one see what is out of sight. It appears.

Indigenous and popular artists, from how they respond to reality, attack the gaping wound that the Western conception of art history has left open. The work of the Museo del Barro gives evidence these other processes and contributes to the continual shaking up of the borders that have been, perhaps for way too long, unmovable.

From ñande to ore

Figure 4: Seminario, Espacio/Crítica, 2008, Museo del Barro, Photo: Rocío Ortega

Figure 5: Seminario, Espacio/Crítica, 2012, Museo del Barro, Photo: Gabriela Ramos

In the year 1999, the Museo del Barro contemplated a need in a small group of people concerning the amplification and deepening of formal and informal studies in the field of art, cultural studies, anthropology. This group had come out from universities and workshops with unfulfilled expectations. This is how what we called Seminar Espacio/Crítica was founded. It started with a programme in 2000, called Identidades en Tránsito (Identities in Transit), but later the programmes changed. (Figures 4, 5) That “ñande” narrowed again, but it did so from a new particular interest. It was constituted as a very specific “ore” which mutated, changed. It first started with a circle of people close to the art scene and later it expanded towards students and graduates in philosophy, history, and political science, creating a space of transdisciplinary discussion and generation of thought. A different community of meaning had been gathered around the Museo del Barro, and for many people it would constitute their main source of academic training.

The path

The seminar “Identities in Transit: The Challenges of Art in Today’s Paraguay” started in 2000. The seminar was structured in weekly meetings, and though it was open to any interested person it was specially promoted among students of architecture, philosophy and the visual arts, as well as cultural promoters and artists in general. During this time, the seminar was organised through a scholarship programme to which candidates had to apply each year. The programme of the Identidades en Tránsito seminar, managed to consolidate itself as a centre of discussion able not only to incorporate poorly debated issues in Paraguay, but also to link disciplines and study areas, which in this country run separately.

Later, the diverse programmes derived from Critica Cultural (2003–2008) helped consolidate even further what was eventually seen as a sort of club of thought which, concurrent with the attendance of its participants, went on to create the necessary space for a research instance under the tutorship of specialists. This process enabled the development of small pieces of work, written texts, which, in a country of little written tradition, ended up being of vital importance. There are very few research centres in Paraguay. Most of the time, researchers and thinkers (specially relating to culture and transdisciplinary visions), carry on with their work in isolation, given that universities have not been able to respond to the research preoccupations of their students and alumni, who are forced to work independently.

The project named Estudios de Contingencia (Contingency Studies), developed between 2009 and 2010, was designed as a continuation of the original project created by Ticio Escobar. Although the academic programme remained the same, the requirements for application were modified in order to amplify the reach of the seminar and to achieve a more transdisciplinary scope. The strategy behind these changes was to stir disciplinary fields that are sometimes tightly closed and to stimulate junctures among them. Image, literature, politics, art, popular and indigenous culture, urbanism, subjectivity, the market, subaltern studies and feminism were the areas of interest which exerted tensions and exchanges among each other during the course of the seminar.

In 2011, the programme continued with the format adopted in the previous year, though changing some of its topics. Contingencia Poscolonial (Postcolonial contingency) represented a continuation of the process initiated by Estudios de Contingencia, and also the introduction of a topic that had not been explored in depth by the seminar up to that point: subaltern, postcolonial and → de-colonial theories. Using these theories as tools, it was the objective of the seminar to relate its discussions to the 200th anniversary of independence, introducing a critical view of these events. In 2012, the seminar opened its programme Disruptive Images, which tried to take into account what happened in Paraguay that year: a massacre of peasants and the dismissal of President Fernando Lugo, through a manoeuvre known as a “parliamentary coup”. The idea of the seminar was to try to analyse and understand what happened through images.

A two-way street

The Museo del Barro and the Seminar Espacio/Crítica arise as obvious needs from bounded groups of people which in certain circumstances allied themselves with diverse groups in order to amplify the idea of that exclusionary us. That small us that was a group of artists creating forms of resistance within a country of various dictatorships, saw in the negation of works from popular and indigenous cultures a form of enslavement, so it supported and fought in → alliance with them, for the recognition of their cultural specificities. That moment in which they themselves were subversive subjects was important for understanding the struggle of other subaltern sectors with less opportunity to become visible. That us, composed of a rather urban group, with access to superior education, opened the circle to the peasantry, the rural, the indigenous; those other ways of erudition that confront Western knowledge from its own existence.

From that open circle idea, the need to establish something small can be seen; an “us” that moves for a more particular interest. In this context, the space opened by Espacio/Critica is almost an expanded field of thought that arises from the concerns of the Museo del Barro around culture, as it attempts to establish links with different isolated instances. Later on, these links give way to other instances which achieve, once again, expanded fields and enlarged possibilities, opening the game to new groups of people that have not passed through supposedly adequate channels, “licenced” to move and work within a specific field of action. Its effect within the scene is bold. Its participants, those who have accomplished to produce and settle down in or out the scene, get to install themselves in their universes, from a different place. They try to impose a difference in a place that doesn’t provide many stimuli to the production of thought. Obstinately and moved by pure desire, they produce, write, publish, practice teaching (some in universities and others in open spaces outside the academic sphere). They manage, as small representatives of contingency, to exist in a manner of pockets of resistance.

From ore to ñande and vice versa, a street that comes and goes, a two-way street that doesn’t cease to reconfigurate itself and to take the form of what is perceived as need, as desire, as strategy of visibilisation, as fights, small or large, as communities of meaning.