This writing on translation includes one children’s song, one musical composition, two tales about one university professor, one good window, a mention of average windows, one quasi-scientific article, one highly incriminating interview and one design biennial; not necessarily in this order. They all aid to illuminate various institutions of human making and are instrumental in questioning what such institutions truly achieve.

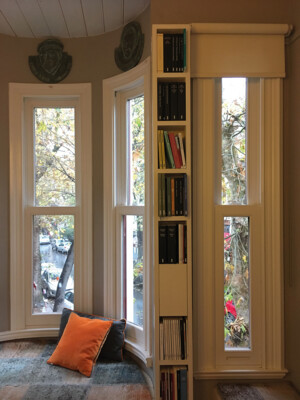

Figure 148: A good window. Courtesy Selda Baltacı Mimarlık Atölyesi.

The good window showcases material translation in the case of a house renovated to become a bookshop. Its typical late 19th century wooden frames are made up a series of laths, which scale and resize the building in perception. Not ornamental but surely elegant in positioning, this good window is attained merely out of a dedication to exact translation. The average windows of our days though, depend on cost and heat efficiency, and are made of coarse, synthetic material. (Figure 148)

What the professor expressed in a fleeting moment of one of the many architecture studio sessions was a salute to the wooden window frame. He spoke of its section as not being a late technological wonder, but a structural linearity. How do you catch that one tiny moment that none of the twenty other pupils do? A perspective for a perspective on materials…

Hear this song:

Twinkle twinkle, little star, how I wonder what you are!

Up above the world so high, like a diamond in the sky.

Twinkle twinkle, little star, how I wonder what you are!

Apparently this tune was a popular European one that was made even more popular by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart when he started playing it in 1761. The professor had his fascination with a vision for curiosity. It was another crammed studio session when he stressed the difference between the two versions of the song, one with the English verses and the other with Turkish. I tend to protest generalisations and comparisons, as they tend to suggest that we better form the exact same perfect human institutions. However, I had to hand this one to him, as the Turkish lyrics would substantially deviate from the ones above and fully manifest two impassable institutions of the culture. Hear this:

Daha dün annemizin kollarında yaşarken, [Just yesterday we were living in our mothers’ arms,]

Çiçekli bahçemizin yollarında koşarken, [Running in our flower gardens,]

Şimdi okullu olduk, sınıfları doldurduk. [Now we are all schoolers, filling all the classes.]

Sevinçliyiz hepimiz, yaşasın okulumuz! [Exhilarated we all are, long live our schools!]

Last year there was a design biennial in Istanbul. I was asked to write a review of it. It was tough because it was a good biennial. Numerous works across disciplines, many ideas – old and new but maybe new to the context – and record attendance. It was a good biennial. It was called Are We Human? Design of the Species. It was all good but felt 3D printed good, not wooden frame good. It was hard to point at what was lacking in the translation of the thought to the space. I was left wondering; “Are humans designs or institutions?”, but more importantly “Are all intellectual accumulations to be translated into exhibitions?” They say “Yes!” nowadays. They say architecture lost its grip with theory and works mainly through exhibitions. Maybe that’s what makes them feel 3D printed.

“The elitist, obscure, rather smug art that we’ve had over the last five or six years is part of the sort of metropolitan stubbornness that Brexit reacted against in my country, and that the Trump voters reacted against in your country”, says Adam Curtis in an interview by Loney Abrams at artspace.com. Curtis continues: “Ever since the 1960s there has been this idea that the function of art is to change the world, and it will do so by changing the way people think and see. Whereas I think, if you look at the history of art, really brilliant art steps back and shows to you clearly what really is going on in the world you live in, in a vivid, imaginative way.”[1]

That reminds me that inclusion is as bad a translation of human institution as exclusion. It seems that a human’s greatest investment is in agreement, but only with her own ideas. I look up for → evidence and get at least one Yale behavioural economist showing that the use of reason actually aggravates partisan beliefs. Dan Kopf’s article on qz.com suggests that “rather than using our best thinking to reach the truth, we use it to find ways to agree with other in our communities. ‘The process is called biased assimilation,’ says [Dan] Kahan. ‘People will selectively credit and discredit information in patterns that reflect their commitment to certain values.’”[2]

The human, in an ideal world where it is neither designed nor instituted, has one extreme potential to go beyond all that is projected for it and that is inconsistency. Where the institution is as resilient as its consistency – only of its services – the human in it is actually free to change minds. The long tale of rationality sure has drowned in a rush to form packs and conform to expectations. There, inconsistency is the only promise for a sudden break. The art institution, with its sturdy tradition as well as myriad of contemporary challenges, holds on to its position at the forefronts of conversing societies merely for the genuine curiosity instilled in its humans. Could it now be the ideal time for an exact translation of this curiosity rather than its well-elaborated end products?