At M HKA, the Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp, we have discussed the overall term “historicisation” from what we imagine it is a local point of view. Although our city is located almost at the epicentre of Western Europe, in what Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas has famously termed “Eurocore”, and although it is a commercial hub with a port that is still one of the twenty largest in the world, Antwerp itself is surprisingly inward-looking. Sometimes it feels as if this whole area – from Hamburg in the north to Paris in the south, from London in the west to Frankfurt in the east, with the Low Countries in-between – consisted of many different pockets of provincialism, wrapped in a thick blanket of suburban self-sufficiency.

So, how does our geographic position influence our thinking about history and the ways in which it influences how people see themselves in the present? That would be one way of understanding “historicisation”. How does belonging to a “centre” (regardless of the peripheral position we, like nearly everyone else in our region, occupy within it) affect our self-image in relation to the past? Does the “safe” location of Antwerp, Flanders and, to a lesser extent, the whole of Belgium inside bourgeois well-to-do Western culture make us less susceptible to playing identity politics with history? The opposite seems to be true, sometimes. There is nationalism, regionalism, localism. There are historical grudges and counter-grudges. Yet historicisation, in itself, does not endorse or promote any particular approach to history. It can be both “positive” (a conceptual device that anchors the present in the past through the slowness imposed by reflection) and “negative” (an excuse to cling to history, or even synonymous with revivalism, eclecticism or other attempts to settle scores with the past).

In M HKA’s more specialised context of Flemish and Belgian contemporary art and visual culture, two remarks on historicisation seem pertinent:

First, as already indicated this part of Europe is wealthy and densely populated, and has been so for a millennium already. Its culture is, broadly speaking, more to do with accommodating new things and ideas into existing → constellations than with creating them from scratch. In a firmly established and supposedly self-assured cultural landscape, there seems to be less need to rely on references to the innate qualities of “nature” or “the people” or other such notions that “younger” nations often use (or abuse) to construct a sense of identity for themselves. Against this background, historicisation might be called the natural cultural condition of the Low Countries, especially of their Catholic provinces.

Second, in Belgium, the “contemporary art heritage” (a somewhat oxymoronic neologism recently coined to name an umbrella organisation for the leading Flemish museums of contemporary art) has, at least since the 1970s, been rather well integrated into the Western mainstream. Artists such as Marcel Broodthaers, Panamarenko, Guillaume Bijl, Lili Dujourie, Jan Vercruysse, Thierry De Cordier, Raoul De Keyser, Marthe Wéry, Luc Tuymans and others are known in a wider European and global context, along with some other art professionals – the recently deceased Documenta 9 curator Jan Hoet comes to mind, but also gallerists such as Anny De Decker and Bernd Lohaus of Wide → White Space in Antwerp (1966–1976) or Fernand Spillemaeckers of MTL in Brussels (1970–1978) and, of course, all those famous Belgian private collectors.

This could be interpreted to mean that historicisation, in our immediate context, is less about restoring the proper place and value to recent local history in the international context, and more about an analysis of history and historicity as overall concepts. And that would not be untrue, but it is worth remembering that the institutional infrastructure for contemporary art remains weak in Flanders, and even weaker in Belgium as a whole. The museums of contemporary art do have collections, but these have not been very strategically configured or sustained. They do make exhibitions that are not without international visibility and relevance, but these “kunsthalle” functions also need to be structurally and financially strengthened.

M HKA’s interpretation of historicisation shall be seen in the light of this structural lack that we are currently doing our best to address and remedy, in a political situation that, despite economic difficulties, appears to focus thought on the future of Flemish culture. We are doing what we can to ensure that M HKA will, in the foreseeable future that is also part of historicity, become a “real” and “proper” museum of contemporary art with good facilities and a strong financial base.

That is one important reason why, after having considered several terms, such as “reconfiguration” or “reconstitution”, for describing how historicisation might address what is to come rather than what is gone, we arrived at the term “reconstruction”. We might say that there is – should be – no deconstruction without reconstruction. That, anyway, is one interpretation of what Antonio Negri said at the L’Internationale conference in Madrid in March this year… In the case of M HKA, it is true both metaphorically, as an indication of our ambition to present an exhibition programme that does not lose itself in the minutiae of art-specific deconstruction, and in a more straightforward way. We are already planning to remodel the ground floor of our building next year, in a move designed to attract and sustain → interest in our collection as we prepare for an anticipated and much more thorough overhaul of our facilities.

There is, as we hope that M HKA’s future plans demonstrate, nothing reactive or reactionary about reconstruction. Instead, we think the term is an example of how the prefix re- can be turned around to point forward, towards a future that has a chance to become brighter. When institutions are reconstructed, this means more than just reorganising or rebuilding them. When terms are reconstructed, there is no need to gut them completely. The lingering resonance of older meanings can be something constructive, such as the echo of constructivism in deconstruction and of deconstruction in reconstruction…

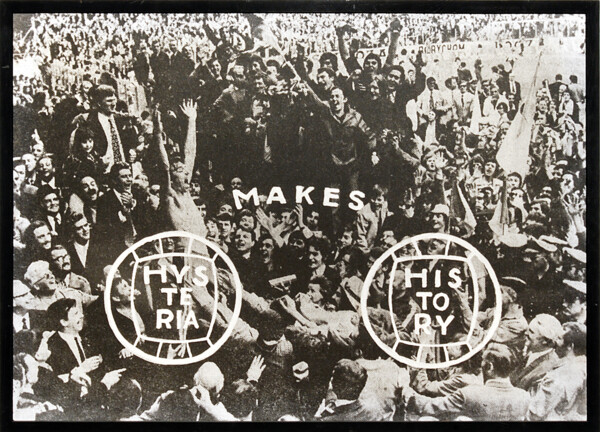

Paul De Vree, Hysteria Makes History, 1973, Collection M HKA, Antwerp / Collection Flemish Community © M HKA.

Hannah Arendt writes in On Revolution that this term was used, before 1789, in a more technical sense (as when we speak of an engine doing “a certain number of revolutions per second”) to describe what we today would probably rather call “evolution”. The unpredictability and violence of the French Revolution changed the meaning of the word and the tone of the prefix that defines it. And then there is “reform”, which can also be interpreted more or less violently, as in the educational or penal systems. Would it be too pretentious to suggest that reconstruction, as a term and a practice, might be used in such a way that it serves both revolution and reform?