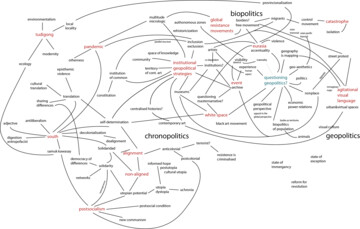

My task is to think about geopolitics in relation to the context of the Van Abbemuseum – a publicly funded, European art museum. With this in mind, I propose the term “white space”. To explore the term I put forward a series of notes, in an attempt to → constellate different ideas and references.

1. The term white space is borrowed from the American sociologist Elijah Anderson. In his essay “The White Space”[1] he reflects on the segregation within urban areas of blacks and whites in the US that still persists today, over fifty years after the civil rights movements, when formal segregation within schools, universities and public space was outlawed. Anderson’s definition of white space is disarmingly straightforward: “For black people in particular white spaces vary in kind, but their most visible and distinctive feature is their overwhelming presence of white people and their absence of black people.”[2] Seeing things, as I do from the vantage point of north-western Europe, Anderson’s definition chimes with the spaces of museums and cultural institutions. Museums, like Anderson’s description of the white space in the US, increasingly see themselves as “diverse”, yet they remain “homogenously white and relatively privileged”.[3]

2. The term “white public space” has been used by Karin Brodkin, Sandra Morgen, and Janis Hutchinson, to analyse the field of anthropology and its “contradictory history or race and racism”. The authors feel the term “puts the emphasis on the social construction of institutional spaces and refers to the implicit and explicit practices, beliefs, and values that govern behavior in them”.[4] Their research exposes the undercurrents of racial imbalance and prejudice that run through the field, the fact that many of the anthropology departments are “white-owned social and intellectual spaces”, as well as the striking misperception from whites that all is well and good. And here one starts to feel a resonance within the walls and structures (both physical and ideological) of the European museums, which are also “white-owned social and intellectual spaces”.

3. The term white space is equally – and inevitably – informed by the current political climate in Europe, characterised by its leaders and institutions’ failure to articulate with one voice its relationship to those who wish to enter from outside its borders. Europe and the West in general, which shows a staggering incapacity to understand the present influx of political and humanitarian refugees as a direct result of its violent meddling overseas, is increasingly projecting itself as a white space. The sociologist Achile Mbembe has written extensively about Europe’s policy of “containment” over the last 25 years, particularly in relation to the African continent “to make sure Africans stay where they are”.[5] Moreover, this strategy of containment is now potently visible in the fences and walls being constructed along Europe’s borders.

Such a strategy has been fuelled and increasingly supported by a surge of nationalist, overwhelmingly white voices (Front National in France, PVV in the Netherlands, and UKIP in the UK, to name but a few), who are using a politics of fear, prejudice and privilege to further demarcate Europe as a white space. And, as I write, in the aftermath of the attacks in Paris, Beirut, Ankara, and California, the nationalist voices claiming Europe as a white space grow louder and more venomous.

4. Ten years ago, in the brilliant essay “Tebbit’s Ghost”, Okwui Enwezor, citing Samuel Huntington, articulated how cultural identity had developed into an exercise of defining your friends and enemies. Enwezor’s words seem frighteningly prescient today: “Within this bleak scenario, Europe has gone to search for answers and perhaps to discover the enemies who so trouble its cultural coherence. In this quest, the immigrant has emerged in the name of the post-colonial subject across the territories of the European Union”.[6] This, Enwezor argues with characteristic bite, is a question of identity politics, “the challenge [of which] cannot be over-stated” for European culture. Yet he also asserts the European artistic sphere is blighted by an “inherent provincialism in [its] current discursive formation”. Here he aims his fire at the European biennial Manifesta, lamenting its then decade-long failure to rethink the cultural space of Europe through its relationships with other parts of the world. Yet such a critique can be levelled at European cultural institutions at large, which remain largely incapable of speaking – and → translating [→ translation] – meaningfully across cultures.[7]

5. When thinking about white space within the context of the European museum, the discourse of the white cube looms large. Elena Filipovic has noted that the white cube has long been understood as “an indelibly inscribed container”. In “The Global White Cube” she neatly points out that if the white cube could accommodate MoMA and the Third Reich it’s because “the display conceit neatly embodies ideas that were useful to both, including neutrality, order, rationalisation, progress, extraction from a large context and not least of all → universality and Western modernity”.[8] Inscribed on the white walls of the European museum, alongside the provincialism Enwezor identifies and the containment of Mbembe, is a history of Western modernity and its confluence with imperialism, colonialism, and exclusion. This “ideological dramaturgy” is the makeup of museums. In that sense, the white space of the museum is not only an “intellectual and social space”, but also a political and historical space as well.

6. In the history of exhibitions, this dramaturgy was most famously laid bare in the geopolitical blockbuster Magiciens de la Terre. In “From the Outside In: Magiciens de la Terre and Two Histories of Exhibitions”, Pablo Lafuente highlights the decontextualising move deployed on the magiciens (rather than artists) from the cultural and political formations out of which they emerged. This move, however, occurred within the Western construct of the white cube – or the white space. In this sense, as Lafuente rightly points out, the exhibition became “the embodiment of a neocolonialist attitude that allowed the contemporary art system to colonise, commercially and intellectually, new areas that were previously out of bounds”.[9] Here, the West’s push for internationalism and diversity comes unstuck, framed as it is within the ideological and epistemic frame of the white cube – as white space.

More recently, as Zdenka Badovinac writes in her term “→ Institutional Geopolitical Strategies” major Western museums are fervently trying to de-canonise their own collections by acquiring an ever-increasing diversity of nationalities to their museum’s holdings. Yet this strategy, as Badovinac rightly points out, employs “the same geopolitical strategy based on denying their own geography”.[10] We could add to this a denial of its inherent neo-colonial collecting strategy. To shift this, as my colleague Charles Esche has argued, we should perhaps consider that today “the most pertinent question for a European art institution […] is not what art to show, but what kind of politics to stand behind”.[11] A first step might be to acknowledge the museum as a white space.

Figure 71: The 1980s: Today's Beginnings?, exhibition view, 16 April – 25 September 2016. Courtesy of Van Abbemuseum.

7. Of course, calling European institutions on their whiteness is nothing new. In April next year, the Van Abbe will present, as part of its exhibition The 1980s: Today’s Beginnings?, a chapter on Black Arts that emerged in Thatcherite Britain. (Figure 71) This extraordinary confluence of artists, filmmakers, thinkers and government policies, precipitated in large part by the civil → unrest that occurred in cities across Britain, but which had its roots in the wave of → migrants, largely Caribbean, that arrived as part of the “Windrush Generation”, directly challenged institutional white space. In his searing text “Preliminary Notes for a Black Manifesto”, which appeared in the first of three editions of the journal Black Phoenix (1978), Rasheed Araeen laments the dominance of Western art practice and discourse over that of the Third World. Specifically, within Britain, he sees “a mechanism of control, or an attitude, which denies black artists their access to art establishment and their rightful recognition”.[12] Araeen’s text and position laid the foundation for a rich outpouring of discourse, production and policy initiatives in the UK that aimed to confront both institutions and the art world as a white space.

Figure 72: The 1980s: Today's Beginnings?, exhibition view, 16 April – 25 September 2016. Courtesy of Van Abbemuseum.

What is so compelling about the history of Black Art in 80s Britain is the fact that the discourse that emerged was fundamentally two-pronged: It stood “against” the nationalist, exclusionary politics so prevalent at the time (encapsulated in the rise of the National Front), including its reverberations in the cultural field. Yet it also stood “for” the positive and → emancipatory exploration of cultural identity within an existing framework. Its aim was not simply to resist white space, but to put forward new positions within that space. In this sense, this was a Fanonian move to → decolonise: by changing the perception of the coloniser, towards both the colonised and, significantly, themselves. (Figure 72)

8. Over twenty-five years on from Araeen’s text, it seems crucial to reflect on the status of institutional white space today. What has happened to the politics and drive that fuelled a political, cultural and aesthetic project such as Black Art in 80s Britain? Whilst there were significant changes, the political climate in Europe in the 1990s, with the flourishing of neoliberalism and its predatory form of capitalism, succeeded in flattening issues of cultural identity. A new form of multi-cultural managerialism set in which, rather than radically shifting how those who occupy and administer white space view themselves – and by inference others – meant that new positions were folded in, subsumed within white “intellectual and social” space.

9. I propose to think about the term white space in relation to the white cube – or substitute the term white cube with that of white space – as a means to acknowledge how the ideology of the white cube and European museum is still indelibly inscribed with the suppositions and exclusions that were its founding, and that still resonate across so many spheres of public space today. In this sense, introducing the term white space is perhaps what Badovinac calls an “Institutional Geopolitical Strategy” to challenge the white cube as a “white intellectual and social space”.

The museum as a place where white space is physically, graphically, and conceptually laid bare must be challenged and transformed. This means inverting Elijah Anderson’s definition so that a museum is a site where the geopolitical make-up of Europe today, and its position towards those outside its borders, is acknowledged and confronted. This would firstly entail a shift in how the white space of the museum sees itself – the Fanonian acknowledgment by the coloniser that he is an oppressor that is necessary in any process of decolonisation. Acknowledging that the European museum of today is an overwhelmingly white space is a small move in that process.