What we mean when we say “left” and Yugoslavia are actually the three historical sequences which some political philosophers address as the “politics of rupture”; something that was completely different from the established state politics in Yugoslavia of that time. Those three sequences were the Partisan liberation struggle, the → self-management, and the non-aligned movement. But when we discuss the emancipatory potential of these historical sequences, we also bear in mind the specific cultural production of that era, which was inevitably linked to the social revolution and which had a deep impact on the cultural politics in Yugoslavia after the Second World War, especially after Yugoslavia’s break with the Soviet Union in 1948. The question is: why were these “cultural revolutions” so significant?

Here we have in mind, for example, the art of the Partisan resistance during the Second World War. This cultural revolution did not only transform the inner order of culture or the position of the cultural sphere in the social structure, but, as Slovene sociologist, Rastko Močnik suggests, it eliminated the cultural sphere, which by its own existence embodies the “barbarity of classes”, and re-established culture in the sphere of emancipation. In Slovenia the case was special, because the liberation movement was not directed by the Communist Party but by the Liberation Front which was an organisation that united a variety of antifascist groups, including cultural workers. Miklavž Komelj [1] noted that Partisan art of the Second World War was inherently political due to the circumstances of its origin. In this context poetry equalled combat, or to put it differently: words became weapons. This is a really important point for today’s debates about culture as a → common resource, about the democratisation of culture, access to culture, transversality and so on.

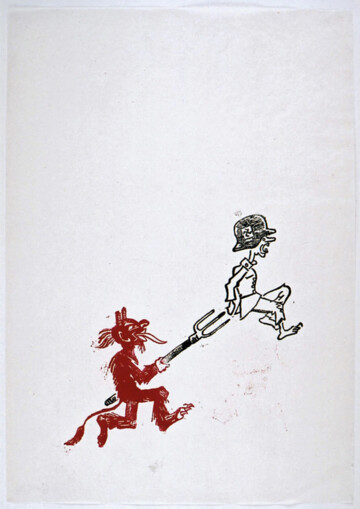

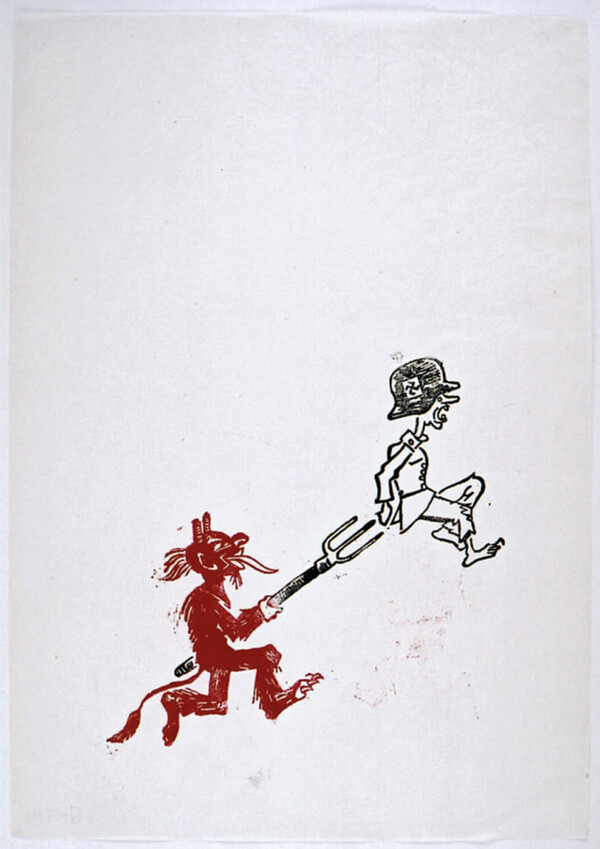

Nikolaj Pirnat, The Devil Stabbing a German (caricature), two-colour linocut, NN. Courtesy of the National Museum of Contemporary History, Ljubljana.

The second rupture is the historical sequence of “self-management” which had a profound influence in the sphere of culture as well. We are of course not saying that this model, which was imposed by the State, and by the Communist Party in particular, is something that can be taken for granted, because in the end it failed to be part of the actual struggle and became rather just a formal stance used by the ruling elite, very often highly → bureaucratised and a kind of farce. But in another way the 1950s was also a period of cultural blossoming in the former Yugoslavia. For example, the formal status of a freelance cultural worker was introduced, part of the national budget went towards numerous cultural activities, and modernism was introduced as the favoured style. Some of the main concerns of Yugoslav cultural policy at that time were including culture in the entire socio-economic context, and transforming citizens from passive users into active co-creators of culture; which is definitely something that could also be observed today in the context of the “commons”. The emphasis was thus placed on the educative function of culture rather than on the artistic one, and museums were encouraged to address the entire working population. This was what the idea of self-management was about – every worker was brought into the decision-making process, including in culture, where the workers were called “cultural workers”.

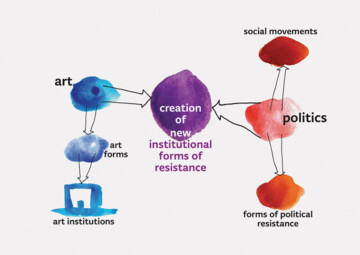

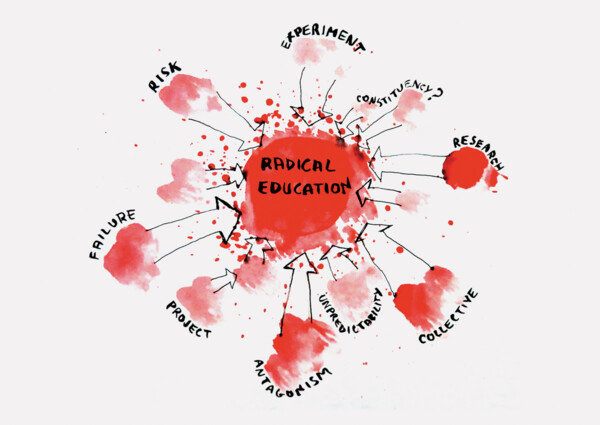

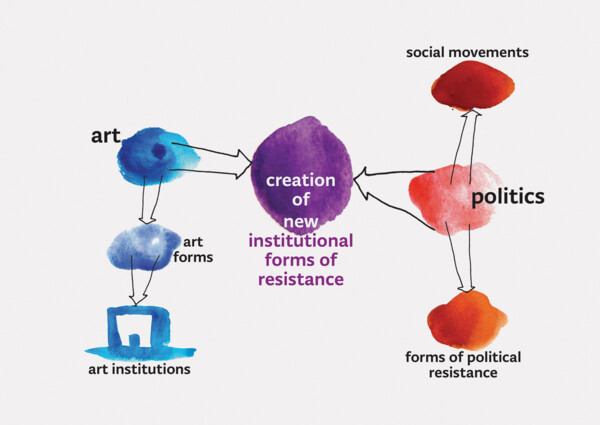

These ideas interested us very much, because we could compare some of the today’s ideas about the new types of art institutions and institutional experiments with those socialist cultural policies, museum models and emancipatory utopias. There are also some resonances with many current pedagogical/artistic/political issues around the educational turn. We thus worked in this direction with Radical Education, a collective that was actively engaged in Moderna galerija’s educational programs, linking institutions with social movements and so on.

Đorđe Balmazović, Radical Education, watercolour on paper, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

Đorđe Balmazović, Radical Education, watercolour on paper, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

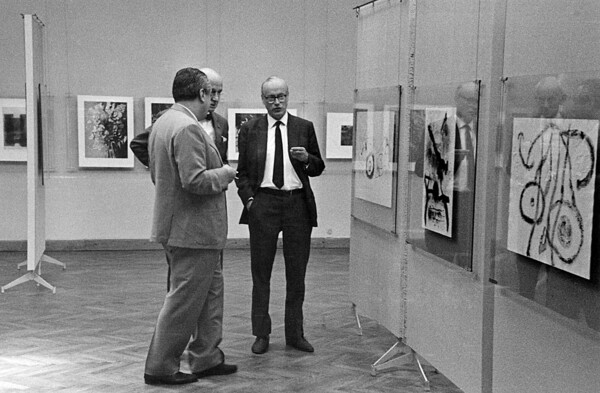

Let us now go back to self-management. These emancipatory cultural practices took many different forms, including, for example amateur cinema and photo clubs, which were established in factories and other workers’ organisations. They provided opportunities for avant-garde experimentation in the spirit of socialist self-management. This was really a special case, because in this way certain links were maintained between the so-called high culture and workers. There were also what was termed “didactic exhibitions on abstract art”, whose aim was to insert the idea of radical abstraction into mainstream art. Moreover, in the museums of modern and contemporary art in Yugoslavia in the 1970s, art was brought out from such institutions and taken to factories, workers’ associations and so on, where special seminars on modern art were conducted.

On the other hand, however, any opposition, even in the form of irony, was forbidden, because socialist art museums were ideologically linked to the officially promoted art, i.e. “socialist modernism” (for example, many Black Wave films were banned, film directors sent to prisons or not allowed to film anymore, and so on).

The third rupture that we mentioned was the non-aligned movement, and Yugoslavia fit well into the related discourse. Socialist revolutions had a lot in common with anti-colonial and anti-imperialist revolutions, which made the Yugoslav case of emancipation in the context of socialism particularly significant in this context. The non-aligned movement provided an opportunity for positioning Yugoslav ideology and culture globally on the basis of the formula: modernism + socialism = emancipatory politics. It was Tito who had revealed to the Afro-Asian world the existence of a non-colonial Europe which would be sympathetic to their aspirations. By bringing Europe into the grouping, Yugoslavia helped to create an international movement.

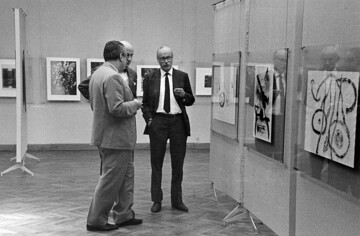

Here we would only mention one very unique case of the Ljubljana (International) Biennial of Graphic Arts, which started in 1955 in the Moderna galerija (in the same year as Documenta in Kassel). Its founder was Zoran Kržišnik, a long-time director of this institution, who saw the biennial as a possibility “for a projection of values such as the presence of freedom, modernity, democracy, openness and so on in society”. [2] The biennial was set up to pave a way into the world, to introduce abstraction to the art world in Yugoslavia (following the period of socialist realism), and to prove that even “fine art can be an instrument of a slight liberal opening”. [3] It combined “a modernist concept permeated by a humanistic desire supported by political aspirations”. [4] Kržišnik stated in one of his interviews that he showed President Tito that the biennial of graphic arts was actually a materialisation of what was being referred to as openness, which was then seen as → non-alignment.

Exterior installation, 4th International Exhibition of Graphic Arts, Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 1961. Photo courtesy of Moderna galerija, Ljubljana.

Installation view with the international jury, 5th International Exhibition of Graphic Arts, Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 1965. Photo courtesy of Moderna galerija, Ljubljana.

Instead of being overly nostalgic or uncritical in accepting the ideas from the past, what we are interested in here are the elements, traditions, and references in those “revolutionary” experiences from the times of socialist Yugoslavia that can be extracted or recuperated to our own times of neoliberal capitalism. How applicable are these ideas for the development of international → solidarity → solidarity. in the sphere of culture today, as well as new models of cultural and knowledge production? What are its emancipatory potentials? And, most importantly: How can we recover the lost and forgotten ideals of the three historical sequences mentioned at the beginning of this text, and how to → translate them into praxis?

Bibliography

Kirn, Gal. “Od primata partizanske politike do postfordistične tendence v socialistični Jugoslaviji”. In Postfordizem: Razprave o sodobnem kapitalizmu, edited by Gal Kirn, 203–243. Ljubljana: Mirovni inštitut, Inštitut za sodobne družbene in politične študije, Zbirka Politike, 2010.