A museum properly understood is not a dumping place. It is not a place where we recycle history’s waste. It is first and foremost an epistemic space.[1]

— Achille Mbembe

For the referential field “other institutionality” the Van Abbe proposes the term “deviant”. Like other terms we have proposed during the glossary seminars, deviant has been circulating within the Van Abbe for some time. It is borrowed from the title of an essay written by our colleague Charles Esche in 2011, titled “The Deviant Institution”.[2] For the Van Abbe, and myself, the term came into focus when I was writing a research policy paper for the museum in 2015. That paper was a process where we were trying to articulate and embed processes of research more explicitly within the institution. The term research was used by different departments (collection departments “researching” the provenance of art works or “research-based” exhibitions), the aim of the paper was to explore what type of research and research-based practice (artistic, curatorial, archival) we wanted to institute and the implications that would have for our working processes. Here the notion of deviance, as I shall discuss, felt prescient (so it is important to understand deviance in this context as focused around research – rather than other types of bodily, → dark room deviance that might be instituted in the museum). The policy paper resulted in the research programme Deviant Practice, involving research projects by artists, curators and archivists. Many of the ideas and reflections, then, as well as some of the examples discussed here, derive from that process.

In its simplest terms, to be deviant can be understood as veering off the entrenched path – as its etymology (“de” - off and “via” - way) makes clear. Two paths currently seem to determine the trajectory of the modern European (or even Western European, from where I write) art museum. The first, that came to define the cultural institution, is inextricably linked to and emerges from Europe – and the West’s – understanding of itself and its relationship to others. A self-understanding that was born by the white Enlightenment male subject and a relationship to others that was defined through power (either military or economic), with inextricable links with the formation of the nation state and its ties to both the modern and colonial projects. Here, to be deviant within the museum would be to find methods and forms of knowledge that might expose and unravel those links, as well as the cultural and political formations that gave rise to them. In this sense we can understand deviance as adopting a position vis-à-vis the institution’s historical processes, its forms of projected authority and its modes of categorisation.

Today, a second, equally problematic path pervades, one that calls for cultural institutions to define its success – or efficacy – through numbers: either visitor numbers or the amount of money it can raise. This path has been embedded through the museum confirming and captialising on an artistic and epistemic canon, (as Gerald Raunig states “back to the bosom of the canon, of art historical tradition, of aesthetic rules”[3]), one that is unsurprisingly dominated by artworks, theories and systems of ordering knowledge from Europe and America. This approach overlays one form of hegemonic structure with another – namely that of the market and the attention economy. Both intertwined paths, one formed by Euro- or Western-centric self-understanding, the other the logic of the market, deny space for different types of knowledge and working methodologies to enter the museum – they deny the possibility of other institutionality by demanding that we conform to their logic. At a time when both these systems are in crisis, it would seem vital to try and conceptualise and institute forms of practice that find ways to deviate from these paths, in both methodology, content and historical approach, as a means to unravel different lineages.

Figure 1: Here or There? Locating the Karel 1 Archive, installation view, curated by Michael Karabinos, Van Abbemuseum, 2017. Photo: Peter Cox.

Attempts at resisting conformity have defined or propped up different avant-garde and experimental approaches throughout modernism’s history, which in turn have been successfully folded into and co-opted by the institution at different moments. Similarly, and more recently within the context of cultural institutions, institutional critique and later new institutionalism have found ways to challenge institutional structures that can, by and large, be read in a similar vein of experimentalism and non-conformism that allowed the Western museum to redefine itself and, subsequently, extend its lifespan. Therefore, the term deviant needs to avoid functioning simply as a performative or rhetorical move by the institution to break rules whilst furthering its own self-preservation. Rather, to be deviant within the context of the museum and other institionality should be seen as an attempt to start undoing some of the institutional and political formations that underpin its practices. Therefore, we might understand the prefix “de-” (“off”) in deviance in relation to processes of demodernising, → decolonising, or de-neoliberalising, or de-enlightening that might be part of deviant practices. These deviant approaches might offer a way to question past suppositions and hierarchies. Such an approach has been most theorised in relation to processes of decolonisation, beginning perhaps with Frantz Fanon, where in his searing opening to The Wretched of the Earth he writes: “Decolonisation, we know, is a historical process: In other words, it can only be understood, it can only find its significance and become self-coherent insofar as we can discern the history-making movement which gives it form and substance”[4]. Such “history-making” lies at the core of the museum and its modes of collecting, categorising and presenting art. (Figure 1)

With this in mind, the notion of deviant practice needs to be further conceptualised and grounded in relation to the tools the museum has at its disposal in a way that could genuinely infiltrate the institution’s methods for collecting, mediating and narrating. A first step would appear to be to acknowledge the implications for our processes and timeframes of working, governed as they so often are by the museum’s → event culture. This would mean, as I have argued in previous glossary seminars, that the museum should increasingly understand its work as taking place away from its exhibition galleries, collection displays and public events (the visible – or illuminated parts of the museum).[5] Instead, its work would increasingly unfold through invisible processes and projects, initiated via relationships among different institutions, agents and constituent groups associated with the museum (these glossary meetings being a prime example). Central to this would be instituting different time frames within the museum that extend beyond exhibition cycles, allowing processes of research to take place whose purpose is not wholly defined or determined by public outputs – whether in the form of exhibitions, commissions or publications. Such a move would necessarily entail redirecting budgets away from more visible activities to those that take place amongst different constituents, whether these are researchers, educators or activist groups. Significantly, it would be an attempt to reorient or refocus the museum as an educational, epistemic centre.

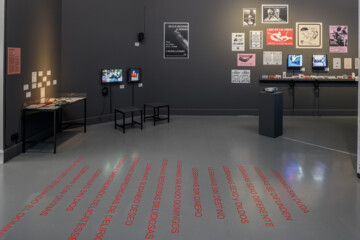

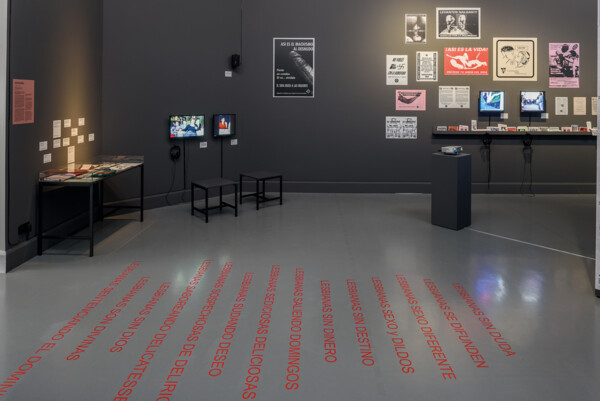

Figure 2: Archivo Queer?, curated by Fefa Vila Nunez, installation view, as part of the exhibition The 1980s. Today’s Beginnings?, Van Abbemuseum, 2016. Photo: Peter Cox.

Figure 3: Archivo Queer?, curated by Fefa Vila Nunez, installation view, as part of the exhibition The 1980s. Today’s Beginnings?, Van Abbemuseum, 2016. Photo: Peter Cox.

At the Van Abbe we identified the → archive and → constituencies as tools or frameworks that might allow these processes and relationships to unfold. Our archives are what defines us as a museum. They are, for better or worse, the heritage we hold. If we accept that deviant practice holds within it the need to consider and undo paths that led us here, the archive would appear to offer the means with which to do that. With this in mind, a formative example of deviant approaches to the archive was the ongoing project Archivo Queer?, initiated by Fefa Vila Núñez, promoter of the artist group LSD, and Sejo Carrascosa of the group Radical Gai – with Andrés Senra and Lucas Platero. Archivo Queer?, housed at the Reina Sofía, consists of an open archive with a → palimpsest of images, publications, videos, oral histories and writings from public performances, actions, parties and campaigns of queer movements in Madrid in the early 1990s. The archive, which was presented at the Van Abbemuseum as part of the exhibition The 1980s. Today’s Beginnings? aims to subvert hetero-centric and patriarchal forms of categorisation through its formation and display. (Figure 2) Central to the project’s methodology and its central question – Can an archive be queered? – is an interrogation of what constitutes an archive and the inherent processes of inclusion and exclusion that are part of the museum’s “history-making” processes. (Figure 3)

At the Van Abbe, we are aiming to introduce some of these deviant approaches to the archive via our research programme which, taking its cue from SALT, issued an open call to artists, curators and archivists to undertake research into the museum’s archives and in → collaboration with different constituent groups. A first step, however, has been allowing the time and resources for a thorough interrogation of our own institutional heritage. The archivist Michael Karabinos, for example examined Karel 1, the tobacco company owned by Henri Van Abbe, the Van Abbemuseum’s benefactor who in the 1930s donated his modest collection of Dutch modernist paintings to the city as part of a deal that would see the → construction of the museum. Karabinos’ research shows that Van Abbe, whose wealth (and ability to collect art) came from the profits of Karel 1, was sourcing tobacco from Java in Indonesia, at the time a Dutch colony, via the tobacco trading markets in Amsterdam. Karabinos’ research into the trading records of the Dutch tobacco markets is exposing how the Van Abbemuseum’s history is tied to the Netherlands’ colonial history and the trading partnerships that emerged from the Dutch East Indies company.

Elsewhere Petra Ponte examined the Van Abbe’s colonial exhibition history through the exhibition TINSA, Tentoonstelling Indonesië, Suriname, Nederlandse Antillen (Tisna), which opened in the Van Abbemuseum in 1949. The Van Abbe was the 17th venue for this vast touring show, which attempted to show “kinship” with the Dutch colonies. Sara Giannini’s research project “Can We Talk about Art with Aphasic Tongues?” examined the extraordinary archive of drawings and sketchbooks of Eindhoven-based artist René Daniëls. Through a series of workshops and performances Giannini proposed both a new relationship with the Daniels archive – one not defined by chronology or biography – and the art work itself, by resisting the stifling restrictions of language.

Figure 4: Ahy-kon-uh-klas-tik, installation view, Brook Anbdrew, Van Abbemuseum, 2017. Photo: Peter Cox.

Deviant research practices, as Francisco Godoy Vega alludes to in his term, similarly need to speak from different subaltern, black, indigenous and queer voices.[6] As part of the research programme the Van Abbemuseum worked with the artist Brook Andrew, on a residency and exhibition that interrogated the Van Abbe’s collection in combination with his own collection of indigenous archives, ethnographic photographs and colonial memorabilia. The outcome of Andrew’s research was an exhibition titled Ahy-kon-uh-klas-tik that combined works from the Van Abbe’s collection, including a Picasso (upended on its side), along with pieces from Wifredo Lam, Gilbert & George, El Lissitzky, Anna Boghiguian, Yael Bartana, Gabriel Orozco, Nilbar Güreş, Keith Piper, and Mike Kelley, as well as Andrew’s own archives and art works, all set with an immersive wall drawing inspired by ancient Wiradjuri carving practices found on trees (dendroglyphs) and shields. (Figure 4) Andrew’s → constellation of art works, references and histories sought to both → decolonise and queer the archive (both through content and through its approach to historiographical). In this way it points to ways in which our museum’s heritage and its methods for ordering and classifying knowledge might be brought into the shadows allowing other histories, voices and narratives to emerge.

The examples of Andrew, Karabinos, Ponte and Giannini’s research begin to explore what a deviant approach to the Van Abbe’s history might yield in terms of offering alternative histories that expose the interconnectedness of its modern and colonial legacies, as well as new ways of reading its archive and collections.[7] But what would it mean to deviate more radically from the types of knowledge that the museum is accustomed to fostering and facilitating: namely disciplinary knowledge such as art history, critical theory, and so on? How would more structural relationships with different types of knowledges affect the research we are involved with and the outcomes it yields?

In closing, it is worth considering L’Internationale as a potentially deviant structure or institutional mechanism. It seems that L’Internationale’s transversal make up – across different historical, social and political context, as well as the different scales and legal structures of its partners – mean that it cannot be determined, tied to or governed by one path. It constantly needs to traverse them. Equally, as a confederation that is not tied to a single city, regional, or national identity, but one that claims its ethics are “based on the values of difference and antagonism, → solidarity [→ solidarity, → solidarity] and commonality”, there appears the potential for forms of deviance that would be harder to galvanise in single institutional, regional or national institutions. Its potential organisational structure and partners across different knowledge centres (museums, universities, archives, activist groups) and constituency groups might be a way to institute other, deviant epistemological and cultural projects – what Jesús Carrillo refers to as a “→ conspiratory” mode of institutionality.[8]