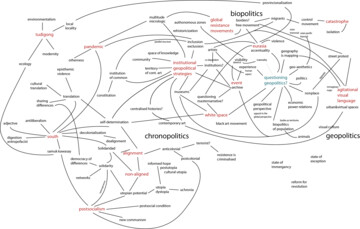

In recent years, the ongoing economic crisis and era of austerity have brought new episodes of antagonism and → resistance onto the streets across the globe. In this context, as a graphic designer exploring the impact of visual communication in the wider society, I developed practice-led research that seeks to determine similarities in the agitational visual languages used to support the grassroots movements that emerged in response to this economic and social crisis. For the seminar Glossary of Common Knowledge, the term “agitational visual language” is utilised to discuss a series of events in Greece. The term is used as an attempt to examine both geopolitical characteristics, as well as common visual elements in the pattern of social movements that have arisen in Greece and other parts of the world in recent years. It describes visuals and graphics that → intervene in the spaces where the socio-political discussion takes place. Within this framework, the research examines the work of groups or individuals who design the organs of information, such as signs, posters, publications and printed or digital media, that comprise crucial components of the public sphere. As Douzinas stated in Philosophy and Resistance in the Crisis, comparable landmark events have the potential to dialectically shape our collective history (Douzinas, 2013). As such, this text focuses on visuals from a number of pivotal → events from 2008 to the present, such as the 2008 riots, the Syntagma Square occupation in 2012, and the referendum in 2015.

The so-called “Greek debt crisis” and the arrival of the International Monetary Fund resulted in the implementation of “shock-therapy” (Klein, 2007), with hard austerity measures that many described as an experiment to be applied in other countries. In their attempts to save the banking system since 2010, successive Greek governments signed memoranda with the “Troika” (the IMF, European Central Bank and EU). These included enforced cuts to social welfare and workers’ rights, privatisation of public assets, as well as tax breaks for corporations. The social impact of these measures includes unemployment, homelessness, child food insecurity and increased suicide rates. This environment generated a series of responses, in which people took to the streets to protest, occupied workplaces, self-organised and created community assemblies. Agitational visual languages have been located at the heart of these reactions to the crisis, from handmade banners and fly-posters, to digitally disseminated graphics.

The 2008 youth → unrest was a consciousness-shifting period for the new generation in Greece (Vradis & Dalakoglou, 2010). The protests that started on 6 December took over several cities in the country after the police shooting of the fifteen-year-old student Alexis Grigoropoulos in the district of Exarcheia in the centre of Athens. Some suggested the riots were a forerunner of the events that would follow and have continued up until the current period of the economic crisis in Greece (Mason, 2011). By discussing a number of visuals utilised by the protesters during this period, we encounter communication tactics that both reject the dominant modes of discourse, but also, revive and re-use particular aspects of it. As Kornetis observes: “Even though the activists’ repertoire was pretty much removed from the past, their discourse often echoed or reverberated its exact moments.” (Kornetis, 2010).

Figure 1: Fuck May 68, Fight Now, graffiti, 2008. Photo by Tzortzis Rallis.

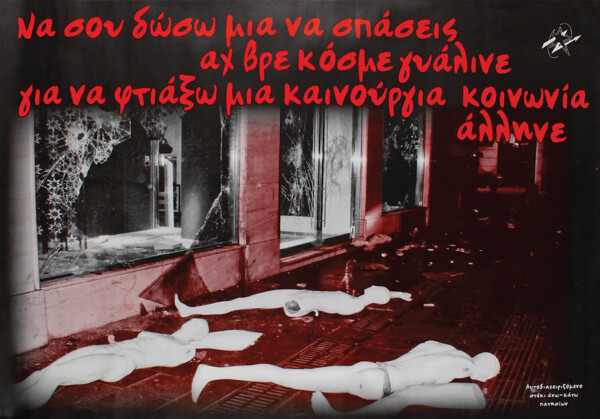

Figure 2: Aftodiacheirizomeno steki Ano-Kato Patision, I will break this world that is made of glass and I will build another – new society, propaganda poster for riots, Athens, Greece, 2008.

Throughout history, political aesthetics have been shaped by the antagonistic tensions between the old and new, and this was visible on the walls of Athens. For instance, the slogan “Fuck May 68, Fight Now” (Figure 1) appears visually-oppositional next to graphics produced by Atelier Populaire during May 1968 at the occupation of the École des Beaux-Arts. Similarly, visuals from the streets of Athens showed an apposite use of popular culture and humour. An important example is the “Remember, remember the 6th of December” stencil that references an English folk verse and the Guy Fawkes mask that was popularised by the Hollywood film V for Vendetta, and then adopted by the protest group Anonymous. In comparison, the poster that was created by the social centre Aftodiacheirizomeno steki Ano-Kato Patision, for the December protests, uses an image of a broken window from riots and the lyrics of a popular Greek song of the 1960s, which translates “I will break this world that is made of glass and I will build another – new society”. (Figure 2) In the following years, forms of visual resistance emphasising the political potential of humour and memes similar to the visuals encountered in the streets of Athens during those events became more popular. Visual memes such as the Anonymous mask, images of police pepper-spraying students in California, or the works of Banksy, are today common tools for political communication. One question that needs to be asked is thus whether such memes have a critical potential to shift the public mindset?

Figure 3: Live your Myth in Greece, appropriation of tourist slogan, 2008.

The 2008 riots were also a forerunner of tactics, networks and visual connections in struggles elsewhere. The use of technology and social media played a crucial role in such mobilisations for the first time in Greece. In the following years, similar tactics and online tools became widespread (Castells, 2012). In the context of agitational visual languages, numerous outcomes were channelled in digital online networks, such as a collection[1] of graphics by Greek designers in response to the riots. Some of the responses focused on the use of culture-jamming and direct provocation, and on the language of the opponents by superimposing the visual language of the official tourism campaign for Greece on the striking images of the riots (Figures 3). Similarly, iconic images of the riots that were shown in the mainstream and online media were utilised in political posters and graphics elsewhere. For example, the cover of the Canadian magazine Adbusters (#82, March/April 2009) featured a masked protester from the riots in Athens. Such images can be interpreted as a symbol of celebration for the new episodes of dissent against the crisis, and a departure from the old ways of communicating visuals.

May 2011 saw the occupation of Syntagma Square in the centre of Athens. Daily assemblies with thousands of participants were organised with a horizontal structure and consensus decision-making processes. The occupation is comparable to the series of M15 protests in Spain and the worldwide Occupy Wall Street (OWS) movement that had an urban focus in public squares to protest against economic and social injustice. In these spaces one can examine a wide plurality of political voices and notable visual connections from the occupation as a synthesis of hand-made banners, signs, tents and assemblies. In I am so angry I made a sign, Michael Taussig discusses the impact of these signs in relation to the audiences living, visiting and observing the occupations in Zuccotti Park in New York: “Most of all, I was struck by the statuesque quality of many of the people holding up their handmade signs, like centaurs, half person half sign.” (Mitchell et al., 2013: 25). The writer traces the form of visual coexistence of the protester and placard, thereby suggesting the significant role of the human aspect in visual communication. Similarly, visual messages were accurately captured by graphic designers that responded to these events elsewhere, such as the posters by the designers Sandy K. in Berlin and Škart collective (Đorđe Balmazović) in Belgrade. Both posters that were included in the large occupational collection, occuprint.org, suggest how the human element can add a personal voice to what are often propagandistic messages. In comparison, the basic but original hand-made placards of the protesters rejected the specialist culture of more commanding forms of political visual communication.

After the violent eviction of protestors from Syntagma Square and the implementation of new austerity measures, a new focus of resistance could be found in the neighbourhoods, with grassroots organisation and people working together, collectively replacing the state and proposing alternatives from below. An important example can be found in the labour clubs, self-organised spaces of workers, the unemployed and students that aim to provide mutual support, cultural events, and education, as well as health care. These structures emerged in several cities in Greece as an alternative response to the economic crisis following the summer of 2011, and the movements that arose in the squares. Labour clubs do not provide charity, but instead focus on forms of practical class solidarity that can be summarised in the classic slogan used on one of their posters: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need”. Since 2012, the labour club in Nea Smyrni in Athens has sought to develop political symbols and local visual campaigns to reflect this new social and political environment. Most of these graphics are designed to be distributed as fly-posters on the streets, as well as to be shared online in order to engage a wider audience in the activities of these clubs. The work of the Labour Clubs can be compared to significant examples elsewhere, such the Spanish housing movement Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH) and Occupy Sandy in the US. These groups are important examples of how community organising can do things where the state does not. Both cases use visual communication aiming to engage a wide audience, utilising graphics that reference simple pictorial alphabets. Such a graphic design approach reflects the historical context and political work of eminent figures in the field, such as Otto Neurath and Gerd Arntz, while they provide a new visual vocabulary, liberated from stereotypical symbols.

Figure 4: The omnipresence of the agitational visual voice on the streets. Photo: Tzortzis Rallis.

In 2015, the first coalition government with an “anti-austerity position” was elected, which called a referendum after months of post-election negotiations with the Eurozone. The referendum occupied a central position in the international media, and asked whether to accept the new series of measures proposed by the Troika , thus presenting a significant challenge to the future of the Eurozone. Nevertheless, many saw the vote as a question of dignity and a unique opportunity to take a stand. The week before the referendum, between bank closures and large demonstrations, the two official campaigns of “Yes” and “No” started. Both campaigns had an appropriate visual style and identity for their target audiences, and the agencies of the relevant political parties. The most pertinent agitational visual voice, however, emerged anew from below, and only the “No” campaign presented such a wave of unofficial messages, graffiti and posters that attempted to oppose the dominant media narrative with visuals (Figure 4). This reality was partly reflected in the class distribution of the vote.[2] In addition, this was empowered by a plethora of messages of support from cities across the globe and through online media and networks of solidarity. In the UK, activists projected messages onto the German embassy in London calling for debt cancellation in Greece, in a practice that connected to OWS as well as the preceding guerrilla visual displays in public spaces by the Stop the War Coalition in 2003. Visual messages that are channelled from the virtual to the physical space reflect the dual character of these mobilisations, as seen in a slogan that appeared in the Spanish squares in 2011: “Digital indignation – analogue resistance”.

This timeline presents a series of events through which members of the public, campaign groups, activists and community organisers sought to make aspects of the ongoing crisis more visible. The agitational visual languages emphasise the antagonistic tensions between the old and new, the importance of humour and the role of the human aspect, as well as the connection between digital and physical political spaces. The analysis of this visual pattern can reveal networks of solidarity, evidence of visual self-consciousness, as well as models for future creative → resistance. From direct action to sit-ins and grassroots campaigns, the use of visual means to amplify social struggles can reflect where potential alternatives might emerge. While the social and economic crisis in Greece is far from over, new episodes will soon illuminate it, and most importantly the transnational struggle of thousands of people crossing the borders of Europe.