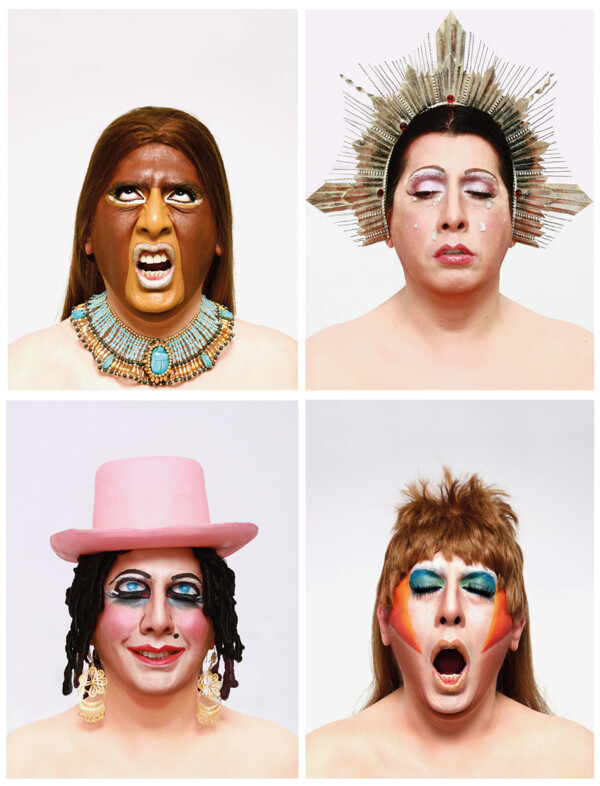

Giuseppe Campuzano, La Virgen de las Guacas, cromogenic print, 70 x 194 cm, 2007. Photo by Alejandro Gómez de Tuddo.

Travesti [transvestite]: Aberrant, effeminate, abnormal, stray, degenerate, common criminal, highly dangerous criminal, criminal dressed as a woman, shameless, sexual → deviant, dressed up, drag queen, anti-social, entity of HIV transmission, scandalous, fake woman, gay, stray gay, gay with a miniskirt, thug, tea-leaf, man dressed as a woman, man in feminine clothing, homosexual, stray homosexual, homosexual dressed as a woman, un-desirable, strange individual, immoral, inverted, gossip, social evil, crazy, crazy street hag, unlawful, scumbag, illegitimate, queer, faggot, fag, erotic minority, paedophile, passive pederast, person of questionable conduct, personality, character, antisocial character, lowlife character, pervert, weird, weirdo, ambiguous being, marginalised being, snitch, third gender, transgender, transformer, transvestite, vulnerable (still under construction)...

— Terms used by the local press to refer to trans people collected by drag activist Giuseppe Campuzano.

Travesti [transvestite] is a popular word in Latin American that means drag. Usually it refers to the person who cross-dresses his body, rejecting any natural or essential identity order. The transvestite makes visible the workings of gender, revealing its contingency as well as the performative possibilities of challenging gendered norms. Transvestite performance highlights how bodies are discursively produced and how identity is never fixed, emphasising the relationship between bodies and subjectivity and tackling a notion of politics concerned with identifications. From a Southern perspective, the concept of “transvestite” could help us to explore the different versions of the politics of becoming. Understood here as an analogy for the mask – the false, the copy, the theatrical, the camouflage – transvestism appears as a useful analytical concept capable of making visible and thinking through the processes of colonisation, resistance, hybridisation, → migration, and mestizaje.

Giuseppe Campuzano, Museo Travesti del Perú, Lima City Centre, Lima, 2004. Photo by Claudia Alva.

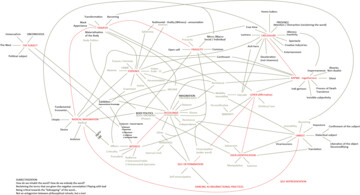

I would like to discuss the term travesti (transvestite) using as a reference the Transvestite Museum of Peru project by the philosopher and drag activist Giuseppe Campuzano (1969–2013), which radicalises the possibilities of thinking travesti as a political tool. (Figure 51) This transvestite museum is an attempt at a queer counter-reading and promiscuous intersectional thinking of history that collects objects, images, texts and documents, press clippings and appropriated artworks, in order to propose actions, stagings, and publications that would → fracture the privileged site of heterosexual subjectivity – a subjectivity that turns all difference into an object of study and renders invisible its own contingency and the social processes that led to its → constructions. The project, halfway between performance and historical research, proposes a critical revision of history from the strategic perspective of a fictional figure Campuzano called the “androgynous indigenous/mestizo transvestite”. Here, transgender, transvestite, transsexual, intersexual and androgynous figures are posited as the central actors and main political subjects for any construction of history. One of the museum’s achievements was to have introduced a politically corrosive and discontinuous narrative of transgender into a public domain, a narrative that imagined new forms of community and undid the foundational myths and ideological fantasy that lay hidden under the rubric of the nation or state.

This is where the transversal readings of the Transvestite Museum became powerful tools for the subversion of heterosexual spatiotemporality: for instance, in the form of micro-cartography based on the concept of pluma (literally meaning “feather”), which connected the grand imperial gown of Manco Capac (the first leader of the Inca civilisation in the 15th century) with the 18th century colonial paintings of the Cuzco School, a movement that appropriated colonial Catholic iconography to represent winged warriors draped in glamorous clothing, and with the costumes of contemporary showgirls and drag queens. Or in the set of images that Campuzano called mestizaje, which wove together representations that provided an account of ethnic and sexual migrations, such as the veiled tapadas limeñas of the 19th century – presences that proved ambivalent and therefore subversive for gender identification – with a transvestite singer from a Chinese opera staged in Lima in 1870, or with images of black queers portrayed by watercolourists from the Pacific Scientific Commission expeditions of the 19th century.

It was there that the importance of the figure of the museum resided. At a time when the market had turned sexual identities into consumer products, and museums seemed removed from any agenda reflecting on sexual politics, the emergence of the Transvestite Museum was an opportunity to redefine the political role of the museum and respond to an official history erected upon the erasure of sexual disobedience. Its emergence was a deliberate perforation of the museum apparatus – which is also a sexual apparatus – at a time when the neoliberal pragmatism of transnational economies and the corporate marketing of the cultural machinery had attempted to establish a hegemonic pattern of the museum. Setting up a Transvestite Museum seemed to declare, on one hand, that the subject had changed and that the historical struggles of “women” and feminism today come up short when they attempt to think about all of our mutant, insurgent bodies, whores, the intersexed, trans people. And, conversely, to choose to speak from the museum was also to state explicitly that the museum is not a neutral technique of representation, but a political device that sanctions the gaze, controls pleasure, and produces sexual identities in the public realm.

Giuseppe Campuzano, Carnet, variable dimensions, 2011. Photo by Claudia Alva.

However, the materials that the Transvestite Museum placed in the public eye did not aspire to a fixed and established identity. Campuzano, and indeed all the museum’s operations, demonstrated a profound distrust of the apparent transparency of images that lay claim to social representation, instead deploying the transvestite strategic gesture as the possibility of betraying their meanings and subverting their uses in the public sphere. His work parodied the rigidity and sharply defined boundaries between genders, pointing out the ways in which these de-normalised practices and drag representations interfered with the social dynamics that shape subjectivity. In this sense, the Transvestite Museum can be viewed as a large → archive of performative practices that defied the sites of traditional analysis of oppression by taking the transvestite body as the locus of enunciation, as a false, prosthetic body “whose nature is uncertainty”. (Figure 52) There is no other truth in these signs than the processes of transformation and dis-identification through which one body can become another. No other reality exists but their frauds and displacements. A new, more fabulous and joyous truth emerges from this very artifice.