Is there a Doel in → southern China?[1]

The threshold must be carefully distinguished from the boundary. A Schwelle “threshold” is a zone. Transformation, passage, wave action are in the word schwellen, “swell”.[2]

From the perspective of a contemporary art museum in Antwerp, a museum that has also engaged in the last two major blocks/corpora in the oeuvre of artist and writer Allan Sekula, Ship of Fools and The Dockers’ Museum (2010–2013), it is quite obvious to propose the notion of the harbour as a topos for the Glossary of Common Knowledge that L’Internationale, the confederation of European contemporary art museums, has been developing.[3]

During our seminar talks (Geopolitics II at MG+MSUM) in Ljubljana, Meriç Öner’s presentation intrigued me. And the thoughts she shared with us on the term “→ instant” – as “a chance to break away from time, space, and the constructed human mind” – triggered my bringing into the discussion the literary term “tarrying.” [4] I would first like to respond to her “instant” with “tarrying” and then come back to discuss “harbours”, the term M HKA is proposing.

In his book Über das Zaudern (2007), translated On Tarrying (2011), the German philosopher Joseph Vogl seeks to unpack the notion of tarrying.[5] In tarrying, he sees the potential of motion set forth precisely out of movement and motion itself. Tarrying does not suspend action. Rather, it marks an interstitial space between acting and not acting, an interspace, in which contingency is revealed. It contributes to the complexity through which events in history may be traced back to their point of origin in order to be revised and set forth. Vogl understands tarrying not as passive hesitation or indecisiveness, but rather as an extremely active state and moment of great intensity. A moment that denotes the → interval, a temporal suspension. As such, tarrying arrests the flow of movement. It resists mere continuation. It marks an incision, a break, in which potentiality is augmented. This interruption nevertheless remains relative to its inherent movement. Hence tarrying, as Vogl underscores, cannot be reduced to dithering or indecision. Rather, it allows for moments of conscious reflecting in a time of instantaneous judgement.

Tarrying, for Vogl, can be understood as a countermove: the advancement of our “reality” is interrupted in tarrying. Tarrying, implies the intuition that it could be otherwise, that an alternative may be possible. Vogl offers an analysis of tarrying as a sustained mode of subversion. Our present time, he writes, is characterised by the constant preparedness for attack: “Aiming and targeting make up its programme.”[6] What possibilities, he asks, remain at our disposal? For Vogl, it is precisely the arrested time of decision-making, in which decision-making itself is suspended temporarily. Tarrying, Vogl explains, means such state of suspension – distending and enlarging the present.[7]

Tarrying is elliptical, rather than denoting a full stop: it disrupts linearity.[8] In this way, tarrying, according to Vogl, opens the → temporal, spatial gap; it is both “is and isn’t”, “may and may not”. It is as a point of disorientation to orient oneself. Hence, tarrying, as far as Vogl is concerned, allows for a going backward and forward. It allows for a shift in direction, a change in speed and tempo. Tarrying understood in these terms is a space, opened to potentiality.

“Now the fact is that the world is notoriously und uncommonly manifold, which can be put to the test at any moment if one just takes a handful of World and looks at it a little more closely.”[9]

What follows is a reworked script for my presentation at MG+MSUM.

From outer space to the harbour

In Historiae Animalium, the Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner writes about a Jenny Haniver in the 1550s. It is one of the earliest entries of this seemingly “outlandish” creature. Jenny Hanivers are actually modified taxidermied ray, skate, or guitarfish carcasses that populated the Belgium ports in the 16th century. At that time, it was believed that the creatures had magical powers. Often, the carcasses found their way into cabinets of curiosity. The name, it has been suggested, was given by British sailors in their linguistic transformation of the French “jeune d’Anvers” (“youth of Antwerp”) to Jenny Haniver. Yet there is no clear source to confirm this.[10]

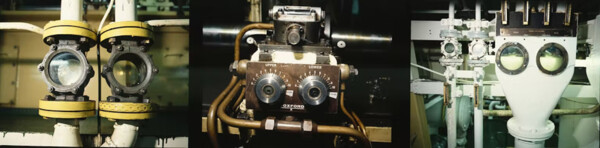

Figure 1: Allan Sekula, Engine room eyes 1–3, 1999–2010, series of 3, 101.6 x 127 cm, chromogenic prints mounted on Alu-Dibond and framed. The Estate of Allan Sekula, Los Angeles.

In keeping with the “outlandish” for a moment longer in our reflections on harbours, we take recourse to Voltaire’s Micromégas for the “extra-terrestrial perspective” it provides us.[11] It is the reversal of perspective, or switching of viewpoint, which is of interest to us here. Writing in 1752, Voltaire employs the literary trope of the (space/sea) voyage. A philosophical tale, as the subtitle indicates, Micromégas, is also Voltaire’s larger-than-life protagonist: a giant from outer space.[12] The inhabitant of a planet orbiting Sirius, Micromégas and his companion from Saturn set out on a voyage in the direction of the Sun in search of other worlds. In their visit to → Earth, wading the oceans, it is in the Baltic Sea that the space travellers finally discover life. Micromégas and his companion first spot a whale, then a vessel. The travellers’ visit coincides with Maupertuis’ expedition. They notice the ship with the scientists on board on its journey back from Lapland, sailing across the Baltic.

Micromégas picks up the ship and carefully lays it in the palm of his hand to observe it. He and his companion show interest in what to them appears in “microscopical smallness”.[13] Despite employing a magnifying glass, the ship’s crew is too small to be seen by the space travellers. In crafting a hearing device, a kind of receiver to render sounds perceptible, it is nevertheless possible for the two visitors to perceive the crew by listening to their conversations. Soon, a dialogic exchange between sea and space voyagers begins. If the tale foregrounds questions of scale and perception, moving from mega to micro and vice versa, Voltaire uses outer space as a reference point to situate this early piece of science fiction.

If the previous seminar on the term “Geopolitics”, held in 2015, seems to have foregrounded terms related to the terrestrial, it may be pertinent to our discussion to consider and connect to those outer spaces that have long been seized by geopolitics, such as the world’s oceans – not to mention more recent ventures into the stratosphere and beyond. The term “harbours” opens up this primarily land-based thinking and lets us understand that space is larger.[14]

We set out to approach harbours – spaces of friction – to reflect on their former function as spaces of encounter, asking: In which ways do contemporary harbours still reflect the relationality of the past (both hospitable to what came from outside and what was a base of departure)? And how may this serve our geopolitical understanding?[15]

In contrast to the inhospitable environment of outer space and the ocean, harbours, etymologically speaking are considered hospitable, safe places, if “harbour”, derived from late Old English herebeorg refers to “shelter, lodgings, quarters”, a “lodging for ships; a sheltered recess in a coastline”, a “temporary dwelling place”, an “inn”.[16]

Antwerp, where the M HKA is located, is Europe’s second largest harbour, after Rotterdam and before Hamburg. Situated 80 kilometres inland, it boasts enormous docks, ships and cranes, as well as the largest lock in the world (Kieldrecht lock) on the left bank of the Scheldt. The river and harbour are subject to continuous dredging for ever more gigantic ships, with deeper and deeper draughts: indeed, in recent decades there have been vast increases in terms of “economies of scale”.[17] If the contours of harbours are not definite, they are persistently retraced as they expand. Zones surrounding harbours lie in an imposed state of suspension: between the no-longer and the not yet. Like the polder village of Doel on the outskirts of Antwerp, to which this text’s opening citation refers to, struggling to survive against port expansion.

In reflecting on “harbours” we draw on the work of the late artist, writer, filmmaker, poet and activist Allan Sekula (1951–2013), in particular, what came to be his final, unfinished project Ship of Fools / The Dockers’ Museum (2010–2013), part of M HKA’s collection. Globalisation – the transformation of the world’s economic system – would not have gained grounds without the transformation of the maritime space, as Sekula poignantly remarked. (Figure 2) A space in which about 90% of today’s global non-bulk cargo is moved inside transferable containers, linking the shifting production sites of the global economy. Countering the myth underpinning neoliberal ideology of “painless flows of goods and capital”, the essay film The Forgotten Space (2009), co-directed by Sekula and the French filmmaker Noël Burch, reminds us that the sea “remains the crucial space of globalisation”.[18] The sea, for Sekula, is a trope of resistance. Maritime space, characterised by its slow and heavy movement, pushes against the common image of instantaneity, weightlessness and connectedness suggested by → air travel and cyberspace.

Figure 2: Allan Sekula, Crew, Pilot, and Russian Girlfriend (Novorossiysk) 1–10, 1999–2010, series of 10, 102.8 x 151.3 cm, chromogenic prints mounted on Alu-Dibond and framed. Collection M HKA, Antwerp.

Harbours, Antwerp & Santos

Sekula’s materialist approach, at stake in The Dockers’ Museum, is grounded in the notion of “objects of interest” in this anti-museum and anti-archive: a non-art collection with objects sourced primarily via eBay. Sekula staged selected objects for the first time in the exhibition Ship of Fools at the M HKA in Antwerp and subsequently at the biennale held in São Paulo in 2010, forging a link between a historic port, Antwerp, and a new port, Santos, today the largest port in South America. The pairing of those two harbours was initially instigated at the level of historical documents (prints, photographs and postcards) while engaging with the local context and iconography. The space of reflection, then, where the artist locates his final project, is the interstitial space of harbours: the intermediary zone of the docks. Its relationality to other ports, to other docks makes it a space of potential linkage points. “The port” as opposed to the notion of the border, Sekula specifies, “can be networked to virtually any other”.[19] What is at stake here is a going beyond binary relations. Sekula reads harbours by way of associating and articulating disparate ports and their workers together through sequential montage.

However, today’s harbours are increasingly difficult to read, not least to even enter. If sailors and dockers once were an intrinsic part of port cities, the last few decades have seen their labour caught up in the processes of automation, dislocation, and decasualisation. If we understand the harbour, akin to Benjamin’s Schwelle, as a threshold-zone, a zone of transit, transition and transport, and by extension the dockworker as an embodiment of this transition zone, what may be perceived as homely and familiar may also be perceived as alienating and estranging. This is how Freud understood the notion of heimlich/unheimlich which he developed in 1919. Note the hinge between both terms. The German term “das Unheimliche” was first coined by Ernst Jentsch in relation to psychology. Writing in 1906, Jentsch in his essay “On the Psychology of the Uncanny” expands on the feeling of uncertainty in the sense of the non-familiar in relation to literary figures, in seeking to discern whether the figure is actually a human being or an automaton, an uncanny double.[20]

Just like the docker has disappeared to a large extent on the harbour side, like the sailor disappeared on the city-side and with it their former places of lodging (think of Antwerp’s modernist building International Seamen’s House here, a lodging/inn and service facility for seafarers which was finally demolished/dismantled in 2013), the historic harbour, enclosing and sheltering with its different functions, has disappeared, and by extension the formerly thriving waterfront culture with its brothels and bars has also gone.

What radically transformed dock labour – and more so the whole port workings, cities and ocean-going vessels in the global supply chain of capitalism – arrived in the mid-1950s with the American invention of the standardised cargo container. An etymological reading of the term “cargo” from Latin carricare “to load a wagon or cart” is particularly telling here. “Cargo” shares the same roots as the term “caricature”, which may point to its subversive potential.[21] In the act of passing through or across, in the passage from one place to another, the container withdraws from accessibility and visibility. By doing so, it suppresses the capacity to perceive and differentiate (consider the suppression of smell here). The second invention, also American, which globalised the labour market for seafaring was the so-called flag of convenience registry. This breaks the link between a ship’s flag and its actual ownership to avoid regulation. The global system has thus seized harbours as its support structures while keeping the cheap labour it needs under the flags of the convenience system.[22]

However, “because of the transverse nature of global flows” it is nevertheless possible, as Brian Holmes has noted, “to draw on the experiences of faraway acts of resistance”.[23] In this respect, the dock worker becomes a connective link to social struggles elsewhere in the world. If the harbour contains the potency of the in-between, further characterised by the potentiality of interruptions and intervals, in keeping with Holmes, to sense and engage in “the dynamics of resistance […] across the interlinked world space is to recall “the solidarities and modes of cooperation that have been emerging across the planet since the late 1990s”.[24]

One such act of recalling and revisiting for Sekula in 2010, roughly ten years → after the WTO protest in Seattle, was the voyage of the Global Mariner, a converted cargo vessel, which circumnavigated the globe between 1998 and 2000, visiting 83 ports. A “meta-ship sailing in defence of the invisible toilers of the sea”, the activist vessel carried an exhibition about working conditions at sea, campaigning against the flag of convenience system.[25] Sekula chronicled part of the voyage and the ship’s crew in a sequence of photographs and slides under the title Ship of Fools.

Why the docker?

With The Dockers’ Museum, Sekula reintroduces the figure of the docker and with it a large spectrum of working gestures and militant traditions at stake in harbours around the globe as sites of democratic struggles. Reinscribing the figure of the docker into the harbour, metaphorically, but also concretely, is to reinscribe not only an embodied way of experiencing the world, but also human agency “in the face of an automated, accelerated, computer-driven, and increasingly monolithic maritime world”.[26] Reinscribing the figure of the docker is at the same time recalling the many, now historic acts of mutiny, strike and protest that were instigated by sailors, dock and shipyard workers in the past, struggles that were fundamental to the formation of self-organised workgroups and autonomous trade unions.

Havens and Seas

Voltaire, in a letter dated 22 August 1753, notes sailors’ reflexive looking back on their adventures from the “safe” point of view of the harbour. Yet, he concedes, he does not know whether there exists such thing as a safe haven in this world after all.[27]

Ten years after the events, the Italian activist and intellectual Franco “Bifo” Berardi wrote a short manifesto marking the anniversary of the WTO protest in Seattle. In “Ten years after Seattle. One strategy, better two, for the movement against war and capitalism”, he argues for a withdrawal into safe havens (“haven” from Old English hæf “sea”, with the figurative sense of “refuge”, now practically the only sense used),[28] not least to create a safe haven after all, in which to save the “memory of the past, and the seeds of a possible future” [29] (my emphasis). This move echoes the one made by Sekula when in 2010 he set up his project within the M HKA at about the same time that Berardi’s manifesto came out. The manifesto’s call for a monastic withdrawal was misunderstood by some, causing controversy, but it was not to be understood as a turning away from – but rather a revisiting of – the activisms that shaped those past moments. Nor was it to be understood as an evasion or acedia.[30]

In his manifesto, Berardi calls for culturally elaborating “a new paradigm based on the abandonment of the obsession of growth.”[31] This new paradigm would be aimed at “frugality, culture-intensive production, → solidarity” and at a “refusal of competition.”[32] Both Berardi and Sekula took “ten years after Seattle” as a trigger for their respective analyses. In the case of Sekula, this was to occupy him from 2010 until 2013, the year of his untimely passing. It brought forth Ship of Fools and The Dockers’ Museum in all their complexity.