A feminisation of geopolitics? / Feminising geopolitics

When we reflect on the term geopolitics we deal with some of the most traditional and patriarchal notions of power. It makes us think of political power and the historical relation of state, nation, and material wealth, with the domination of territories and the people who inhabit them. However, I would like to propose a change of this meaning, and to offer a view of how geopolitics, given its etymology (politics of → Earth), should indeed be connected with the idea of what ecofeminism calls the sustainability of life[1].

In this text, I will propose ecofeminism as a possibility to “feminise” the notion of geopolitics. And when I refer to feminisation here, it does not mean to stress what the female subject could bring to the field, nor do I intend to reinforce the binary division of biological subjects (cis-male and cis-women). Instead, this attempt is related to the strong debates caused by the arrival of feminist politicians in the public sphere. As the feminist activist Justa Montero states[2]:

Feminising politics requires looking at the interpretation that the feminist movement makes, of the needs and proposals of women, placing them at the centre of the social, cultural and political agenda. It is to make feminist policies, to build another meaning of what is the policy that addresses and relates the micro and the macro, the personal and the political, sexuality and the TTIP, nursery schools and pensions, and all women and LGBTIQ+ people in its → diversity. It is definitely a change in the idea of politics itself, often identified only as institutional policy.

In a world devastated by → ecological disaster and political injustice, in which big corporations are supported by neoliberal governments and social inequality is on the rise, the alliance of feminism and ecologism has to do with the possibility of changing the direction of a whole planet, with the aim of enabling the lives of human and non-human generations in the future. Two hundred years of feminisms and six decades of ecologism converge in the asseveration that there will be no future at all without the guarantee of a new social contract, and one that requires radical transformations.

Maybe now is the time to reformulate social sciences from an intersectional gaze, which should not ignore the diverse coordinates that need to be considered. Maybe we should contribute to feminising geopolitics. Here, ecofeminism could be a key to seeding a bit of hope in the world.

Ecofeminism because...

First of all, I believe that the feminist movement is one of the most potent political projects of our time, and it is constantly producing knowledge and new strategies of resistance to confront the different ways of oppression in this neoliberal era.

Secondly, ecologism is a space of action that points out that we are going through a multidimensional economic and ecological crisis whose roots are also found in social reproduction, political legitimacy and the failure of traditional values. Both activisms represent, somehow, two political subjects that have been reshaped in the collective militancy of a new generation that today yells: “Our house is on fire!”[3]

Despite the obvious gravity of the situation, it seems that until recently it has been politically and socially unnoticed. According to the anthropologist and ecofeminist activist Yayo Herrero, beyond its nature of critical thinking, ecofeminism is also a social movement that analyses the capitalist-ecocide-patriarchal and colonial system we live in, and it is trying to oppose the hierarchical culture that considers that some lives are worth more than others.[4]

Following Herrero, we cannot deny that from the moment we are born we are ecodependent and also → interdependent (a notion widely used by intersectional feminisms). She also states that the very possibility of existence came from practices of → care (→ care), sustaining the material conditions needed for live, and lastly from giving and receiving affection. Elements that represent both feminist and ecologist practices.

So how can we put these practices in the centre[5] to analyse the concept of another possible geopolitics?[6]

Artistic approaches to keep life alive

As on many other occasions in the past, an artistic sensibility has proved to be a crucial tool when trying to expand ontologies that seemed, at first glance, immutable and set in stone. I want to bring some examples to the table in what follows.

The work developed by the international research group Planta is dedicated to the articulation of → situated practices, ones that reflect on the relationship between humans and plants. Their research on, with and for plants is activated with different → constellations. As they say in the statement, they are artists, dancers, choreographers, plant carers, activists, feminists, fermenters, kin makers, witches, radical faeries, ecosexuals, pole dancers, friends, lovers, animals, symbionts… Planta is a choreographed installation for plants and humans created by a group of dancers and plants. (Figure 1) Their bodies relate to movement, words, and affect, using → queer methodologies, creating a space for cohabitation. It is a celebration of performance as an art of encounters between humans and non-humans outside of normativity.

Figure 1: Planta Performance, Love At First Sight Festival, 21 September 2019, Toneelhuis, Antwerp. Photo: Dries Segers.

“We think with knowledge-as-humus. We are dedicated to the ubiquitous queer knowledges embodied in the entangled performances of the myriad earthlings. Plants and humans are continually affecting/becoming affected by one another in their inter(intra)active becomings. And they are simultaneously shaping and being shaped by a tentacular web of other co-workers...”[7] following Donna Haraway’s recent imaginaries, which we see developed in Fabrizio Terranova’s documentary film.[8]

Planta’s work consists of an old ritual that puts a spell on us so we can open our senses again. Senses we used as part of a communication channel that used to be fluid but is now closed. With their dances, looping echoes, and strange flows that move back and forth to and from the plants placed in the centre, the collective incites us to surrounding them, to feel in a different way their presence and their interaction.

This approach to non-human life is different from traditional → ecologism. What Planta proposes is to perform affected practices with those plants. They proclaim they care for them, they feel them, they feel affection for them. In their work we can hear echoes of the Ecosex Manifesto,[9] by the post-porn star and sex activist Annie Sprinkle and her partner Beth Simons. Sprinkle and Simmons propose eco-sex practices – rituals that imply touching, making love, marriage and so on, with nature – which intersect environmental activism with sexual identity, as a way of defending the planet through love, pleasure, affection and sensual connection with the Earth.

→ After the global protests of the 8 March 2019, and the massive uprising of new young ecoactivist movements such as Extinction Rebellion and Fridays for Future, it could look almost negationist to deny that new political subjects and imaginaries are emerging. These movements show great strength but are always based on non-violent protest strategies. Here we may see the similarities between artists and activists, for they are both part of this new rising tide, and together they bring diverse approaches to the global problematics mentioned above.

Ecofeminist political struggle

The first links between feminism and ecology were established right after several scandals due to the use of pesticides, with a key text being produced by the biologist Rachel Carson, whose 1962 book → Silent Spring[10] was long considered a “bible” of ecologism.

But the term “ecofeminism” was created later, by Françoise d’Eaubonne in 1974 in her book Le féminisme ou la mort[11], in which she analysed the correlation of global overpopulation and its ecological implications with the absence of women’s reproductive rights, and how they were denied the control over their own bodies. With this visionary new concept, d'Eaubonne came up with a name for various practices of resistance and disobedience that had actually started years before, and was also proposing a concrete interpretation of how patriarchal domination was the origin not only of women’s subjugation, but of the environmental destruction of our age as well. This new concept was born as a response to the appropriation of both agriculture and control over reproduction, or in other words, the reproductive work carried out by nature (material reproduction) and by women (social reproduction).

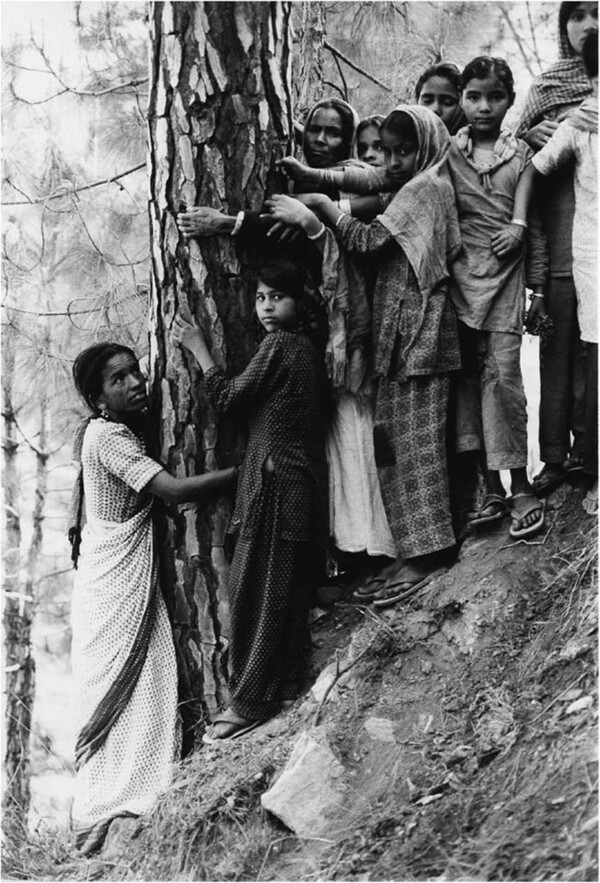

A few years before this, Vandana Shiva and another activist of the Chipko movement, in India, were developing a compendium of practices that have remained as the paradigm of non-violent protest. The movement crystalised the struggle against the felling of the forests and the clearing of the new lands for extensive monoculture agriculture and grazing, which were destroying the resources and traditional forms of exploitation and communal management of the land. The activists inside this movement (mostly women and children), were able to protect communal forests just by the practices of embracing trees, in a collective act of caring in which all bodies were as one, humans together with the trees. (Figure 2) This implies the idea of the embodiment of politics. The potentiality of these practices and the images they generated travelled all over the world. They expressed an urgency to act, to protect what at that time began to be conceived of as a common good that was taken from us by capitalism – the Environment.

Figure 2: Women and children of the Chipko Movement in a protest, 1973. Source: World Rainforest Movement.

Chipko Andolan, was a forest conservation movement in India. It began in 1973 in Reni village of Chamoli district, Uttarakhand and went on to become a rallying point for many future environmental movements all over the world. Photograph year 1973

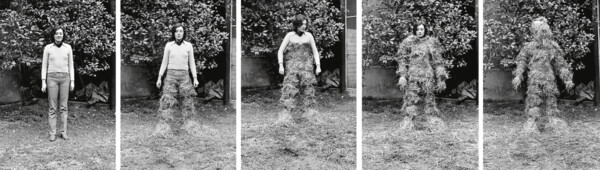

In the 1970s some conceptual artists were dealing with this embodiment of nature and politics, using visionary metaphors of what we can nowadays read as feminist paradigms. We may find them in Ana Mendieta’s Earth body works[12], or in several works of the Catalonian artist Fina Miralles[13] such as Dona-arbre [Woman Tree] (Figure 3), that alludes very poetically to the situation of women tied to social roles that keep them from moving forward.

Figure 3: Fina Miralles, Translations: Woman-tree, 1973, documentation of the action carried out in November 1973 in Sant Llorenç del Munt, Spain, 1973 (1992/2020), silver gelatin photography and inkjet printing on paper, 3 photographs: 39 x 29 x 3 cm and 1 photograph: 100 x 70 x 3 cm 39 x 29 x 3 cm. Courtesy of MACBA Collection. National Art Collection and donation from the artist. Photo: Roberto Ruiz.

At that point ecofeminism was somewhat criticised for having an essentialist approach that entailed the idea of women as almost mystically or spiritually linked to nature. Nonetheless, in the following decades ecofeminism kept exploring new intersections between feminism and social justice.

Territories, land, labour, bodies. The logics of → extractivism

In the 1980s and 90s, with the emergence of new neoliberal forms of economy, capitalism developed more profound and precise ways to capture the raw materials and bodies needed for the extraction of what are only considered “resources”. And these resources never ran out, they were supposed to be inexhaustible, something which the privileged subjects of the Global North could dispose of at will.

Extractivism was a colonial practice of exploitation that started in the 16th and 17th centuries as a form of domination of territories and their communities, and through the enslavement of the existing populations. Mining, for instance, was a key economic activity of Spanish colonialism, and today, not by chance, it is still a very profitable enterprise, now controlled by transnational corporations that have very advanced and accurate technological systems to extract those same resources.

In 2019 Mapa Teatro[14] presented an “ethnofiction” at the Reina Sofia, an exhibition/intervention called Of Lunatics, or Those Lacking Sanity[15] and the performance lecture, The Living Museum[16]. In their works, they create a narrative that links the colonial past with the actual work of some little-known companies, which still maintain the traditional ways of extraction used in the years of Spanish rule. Paradigmatically, they try to survive with those old Master’s tools, that indeed are less harmful to the environment, but of course produce at a less competitive pace or price. In November 2018, the artist Elena Lavellés presented the exhibition (F)Actors en Route at Matadero Madrid, with three works that analysed how extractivism affects the social ecology and communities around it: the extraction of “black gold” from Ouro Preto, within the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil; the extraction of oil in Ciudad del Carmen, in the Gulf of Mexico; and the extraction, and very contaminating transportation process, of coal in Powder River Basin, in the USA.[17] (Figure 4)

Figure 4: Performance by Jana Pacheco and Xus Martínez at the opening of the exhibition (F)Actors en Route, 22 November 2018, Matadero Madrid. Photo: Bego Solis – Matadero Madrid.

During the exhibition’s opening, there was a performance by dramaturgs Jana Pacheco and Xus Martínez, inspired by the work of Lavellés. As the pictures shows, we could see two women standing, wearing dresses that resembled those same mineworkers’ clothes, and they were struggling with the sand placed on the floor of the room, eating it, making quite disturbing sounds and images. They were reclaiming the figures of the miners’ wives, who do not go down the mine but who must clean the clothes by hand, clothes full of toxic and contaminating remains. They, the miners’ wives, are doing work that is completely invisible, but is an essential step that helps the men perform their duty, an additional task put on top of the traditional everyday chores such as house cleaning, food preparation and so forth. Such care work is indispensable for any human activity.

Connected to all this, it is also significative of how the textile industry carries out the aggressive exploitation of both nature and bodies. With the manufacturing of textiles, capitalism began to expand and to create rhizomatic strategies to increase production and imbricate life, labour and identity, with profit as the only possible measure of interest. The images of the tragedy that occured at the Rana Plaza garment factory in Dhaka (Bangladesh), shocked the entire world that day in 2013, when an eight-floor building collapsed killing 1,130 textile workers, employed by corporations like Inditex and El Corte Inglés, among others.[18] Those who disappeared were mostly women, since this is a very feminised industry, in which children often also work as semi-slave labour. The images not only told the story of a collapsed building, but also about the collapse of a whole system, one that can no longer sustain life itself.

Today, in the context of the new rise of feminisms as an intersectional struggle and a globally articulated movement that goes beyond the essentialist subject “women”, ecofeminist thinkers and activists are denouncing the new alliances formed between capitalism, colonialism and patriarchal exploitation.

The case of the female temporary workers picking strawberries in Huelva (Spain), is a very precise example of the complexity of the interconnections of the subjection of bodies, territories and natural resources, to a logic of total exploitation. In the last few years, these women have called out the sexual abuse and horrible threats from their employers, small local agricultural entrepreneurs. After some time, the lack of gender perspective in the recruitment procedures and working conditions became widely known, along with the opacity when managing information about how many women work in this sector, or how they live while they perform their work. This system is called “recruitment in the origin”, where workers are recruited at “home” to work abroad. In Morocco, thousands of women are thus hired to work in the fields of Spain and Italy. Spanish companies go to Rabat and decide the working conditions there, working directly with the state’s government. The classic profile of a strawberry worker is a woman under 40, married and with children under 14 years old. A profile designed to discourage the workers from leaving their country behind and staying in Spain.[19]

Organisations such as Ecologistas en Acción have been highlighting how this massive monoculture of strawberries and other fruits in Huelva is devastating water reserves and causing enormous changes in the environment. But to Yayo Herrero, the problem lies not only in a lack of healthy protocols, as it is also a structural problem that has to do with the notion of production itself, with the transformation of agriculture into an industrial process, focused on the maximisation of profit, exploiting people and nature alike in a patriarchal context.[20]

One global body

According to Verónica Gago[21], in recent years we can see a global articulation of feminism as a politics that makes the body of one, the body of all. The body as a transnational → territory is today once again the object of new colonial conquests and allows us to connect the archive of feminist struggles with struggles related to the autonomy of colonised territories. This body of all feminised bodies is a somato-political archive, following Paul B. Preciado, that has inscribed itself in it the narrative of the history of power, but also of subversion and resistance.[22]

The feminist strike of past 8Ms is a trap for capitalism and patriarchy, because is not only do such actions consist of withdrawing one’s labour, but also of not consuming, and not caring either. This degrowth attitude operates as a whole statement, and the strikes allow us to make visible the various different forms of work – precarious, informal, domestic, and migrant – not as a complementary or subsidiary work, but as the key element of the current ways of exploitation and extraction.[23] It also highlights the difference between those who can and who cannot stop their work.

Ecofeminism show us the potential connection that links the body and the subject, located or inserted in a territory that is physical, social and affective, and relates to the world surrounding it. Everything is interweaved, from the molecular to the global, connecting different → emancipatory practices in diverse geopolitical contexts.