Corrected Slogans is the title of the album recorded by Art & Language with Red Krayola in 1976. This was their first → collaboration, and the result is pop music about the history of imperialism and communism. That slogans should be corrected was discussed by Lenin in 1917, during the spontaneous revolt of the workers in July of the same year. By noticing that political slogans have their own lifetime, Lenin observed that “every particular slogan must be deduced from the totality of specific features of a definite political situation”. This in the case of revolutionary Russia meant that the slogan calling for “the transfer of all state power to the Soviets” was valid only between 27 February and 4 July 1917. After the latter date the call for “transfer” was ridiculous, because the state had used most aggressive means to prevent the existence of the Soviets. In the new situation, only the equal measures taken by the working class (i.e. armed insurrection) could be the answer.

In 1967 Carl Andre came up with a slogan summarising the then actual discussion on the social and political status of conceptual art: “art is what we do; culture is what is done to us”. This is a clear separation of art from cultural assimilation. It is a declaration against the ideological constraints of cultural materialism. In 1973 Art & Language corrected this optimistic slogan by claiming that “art is what we do; culture is what we do to other artists”. It was this question of contamination that pushed the conceptual art group to question what their status in the world of art was.

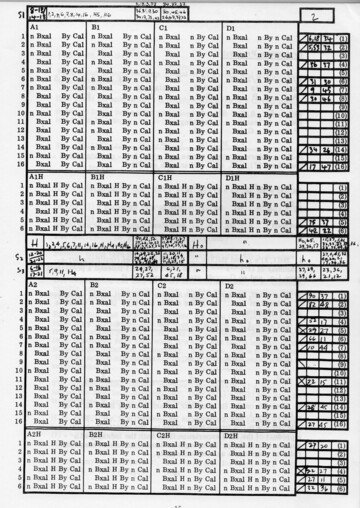

Figure: Art & Language, Blurting in Art & Language, 1974

After their participation at Documenta 5 in 1972, Art & Language was seeking ways to use collective work as a heuristic device for learning and research. The heuristic possibilities of working as a collective were understood as something genuinely against the mediation of institutions. According to Art & Language, the curators and art critics, as the best examples of institutional mediators, cannot introduce anything new to our understanding of the contradictions of art practices. As Charles Harrison once wrote, “when management speaks, nobody learns”. Accordingly, the operations of Art & Language were not divided among exhibiting, theory, criticism, and activism. These were all understood as questions related to practice, and they were all operating in the strange state of equilibrium. As a result, Art & Language’s practice at the same time involved the production of theory (some sort of wild combination of analytical philosophy and Marxism), exhibitions (including exhibitions in commercial galleries), criticism (or as they called it, the “naming and shaming” of mainstream art journalism), and political activism. This last aspect of the group’s practice was the most troublesome, and the most extreme outcome of this took place in the belly of the beast, New York City. What happened is that the group of people involved in the New York section of Art & Language aimed to utilise the group’s practice by conceiving a model that would allow for others that were not part of the collective to use the possibilities inherent in the heuristic model of indexing. The outcome of this was simplifications of referential contradictions (i.e., lessening the conceptual pandemonium), which led to the widening of the group’s structure of organisation. This meant that after 1973, or more precisely after the Blurting in New York project, the social dimension of conceptual art practice became more evident. (Figure) In the history of Art & Language, this meant the collaboration with other art collectives such as AMCC (Artist Meeting for Cultural Change) that led to inner contradictions and fractures. By introducing elements that were foreign to its practice (Maoism being the principal case), Art & Language unleashed unforeseen contradictions that ended up with a few of its members abandoning art altogether for work on unionisation (Karl Beveridge and Carole Conde in Canada, Ian Burn in Australia, Michael Corris in New York, David Rushton in the UK).

We cannot understand this unfolding of conceptual art practice into politics without grasping the fact that at the very core of the radical practice of Art & Language lay an uncompromising detachment from institutions. The main driving force for Art & Language, and for most of the other conceptual artists, was the struggle against the institutional administration of art practices. The real core of conceptual art was never its style of grids, tautology, dematerialisation of art, and the aesthetic of administration. Art & Language did everything to oppose → bureaucratisation. Their momentary union with AMCC was not an arbitrary addition of politics into the art; it was the logical outcome of their artistic practice.

When in 1975 some members of New York section of Art & Language (Michael Corris, Jil Breakstone, Andrew Menard) visited Belgrade and attempted, together with Yugoslav conceptual artists, to index the language used in discussing → self-management in socialism, they wanted to double these contradictions. The main topic of this project was a critique of “cultural imperialism”, but more forcefully it was aiming to open up a space for art that is not mediated by any state institutions. On a global scale, the call for self-management (a project that was never finalised) undermined the ideological postulates of Cold War policies that the artists from the US and those from Yugoslavia were communicating through the channels of state institutions. In Belgrade, in October 1975, this project had an immense influence not only on conceptual artists (especially on Zoran Popović and Goran Đorđević), but also on theoreticians of self-management who in the heyday of questioning the bureaucratisation of culture turned to the writings of artists published in The Fox journal (and especially to Mel Ramsden’s “On Practice”). This aspect was especially strong, since one of the fundamental postulates of Yugoslav self-management was based on the idea of the withering away of the state.

On another hand Art & Language, after the episodes with Yugoslav self-management socialists, Australian national museums, and New York Maoists, realised that they could not stand for both uncontaminated art practices and the organisation of culture. In this moment of dissolving of the core idea of Art & Language (the so-called “monstrous détente”), the group went through a process of retrospection, the lessons of which are still active today. They could have corrected the slogan of conceptual art once more in 1976 by saying that “art is what we do; culture is what we organise together”. Art & Language never did that. Those members who wanted to do art went to galleries and made paintings; the other group that sought to organise the culture dissolved into the union activism and designing banners. The strongest moment of the former was the painting from 1980 called The Portrait of V.I. Lenin in the Style of Jackson Pollock; the latter never produced a masterpiece, but gave clues as to how to “go-on” in the art without exhibiting at all.