Commoning translation[1] renders translation an act of solidarity, not fidelity or loyalty.

Commoning translation is to insist that translation is practiced by many and not by a few.

Commoning translation reminds us that translation is an act of contingency, not certainty.

Commoning translation reskills the task of the translator who is already precarious, already uprooted.

Commoning translation rejects translation as fluency.

Commoning translation mobilises stuttering translators who speak in whole fragments.

Commoning translation asserts the right to translate out of a sense of solidarity with the text.

Commoning translation, translating in solidarity, is not colonial translation, which seeks to uplift or reveal, civilise and sell.

Commoning translation has as its errand to mobilise against white privilege and power, to bring side-lined histories into view.

Commoning translation is to remember that you can know a language for its power to regulate more than for its power to communicate.

Solidarity in translation is not for anyone to claim.

Commoning translation may speak to none or merely a few.

Case Study 1: Letters for Black Lives: An Open Letter Project on Anti-Blackness

In early July 2016, the Chinese-American ethnographer Christina Xu authored and published a Google document titled “Letters for Black Lives”, (Figure 1) prompted by the police shooting of Philando Castile, a black man, and the early misidentification of the police officer as “Chinese”.[2] Two years earlier, Peter Liang, a Chinese-American NYPD officer, had shot and killed Akai Gurley, another black man, in Brooklyn. The 2014 shooting of Gurley, and subsequent conviction of Liang set off a cascade of intra-racial conflict in Asian-American communities in New York and the US, illustrating how loaded such relationships are with regard to notions of anti-racism and social justice (see, for example, Asian-American community fractures with regard to affirmative action in university admissions policies). Many Asian-Americans, especially first-generation Chinese-Americans, did not feel that they needed to stand in solidarity with black communities in their resistance to police brutality, and did not see how Liang was anything but a victim of both the NYPD, which they saw as defending white officers more strongly, and of anti-Asian racism in black communities, a sentiment bolstered by a history of interracial conflict.

Figure 1: Letters for Black Lives Matter, Persian edition, https://lettersforblacklives.com/.

Younger Asian-Americans, on the other hand, felt that Gurley’s killing, and Liang’s subsequent conviction, should be → situated within a broader narrative, and critique, of anti-black racism, white supremacy, and police violence, notwithstanding the fact that Liang was an officer of colour, convicted of a crime when his white colleagues most often were not. Xu’s immediate response two years later, when Castile’s murderer was identified as “Chinese”, was to try to generate a way to communicate why Asian-Americans of all ages and ethnic backgrounds should stand in solidarity with black Americans, and then especially on issues pertaining to structural racism, police violence, and anti-blackness.

Asian immigration to the US was largely facilitated by the passage of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, also called the Hart-Celler Act, and contemporary Asian-America bears the direct imprint of the ideological foundation of that legislation: in 1960, 5% of the foreign-born population in the US was Asian, whereas they in 2014 represented 30% of the foreign-born population. The 1965 Immigration Act was intended to encourage the migration of skilled workers from → Asia, with the result that many so-called “first-wave” Asian migrants came from lower middle-class or middle-class backgrounds and often had some degree of secondary or post-secondary education. The US was at the time seeing an expansion of its welfare state, and the labour migration of these skilled workers was intended to fill out the ranks of professionals who could contribute to that expansion.

At the same time the African-American civil rights movement was unfolding, insisting on social and legal justice for black Americans. Asian migrants, disproportionately middle-class in origins and/or aspirations due to the ideological underpinnings of immigration legislation at the time, were often politically and juridically pitted against African-Americans, whose grievances were rebutted by white policymakers’ assertions that if Asian immigrants could succeed in the US, why couldn’t African Americans do the same, thus cementing the persistent and misleading notion of the Asian-American “model minority”. The model minority stereotype, along with other racialised stereotypes, reinforces the notion of individual character being to blame for systemic inequality, distracting from criticism of a system designed to advance white power and privilege.

As the historian Vijay Prashad argues in The Karma of Brown Folk, anti-blackness has been a central aspect of what it means for Asian immigrants to the US to “become American”.[3] Adopting anti-black beliefs is, according to Prashad, a way to integrate into the US national narrative, which depends on the subjugation and dehumanisation of brown and black bodies, what scholars such as Orlando Patterson refer to as social death. Prashad’s thesis is brought to life in the events surrounding Gurley’s killing at the hands of Liang, who shot Gurley while patrolling stairwells in the Louis Heaton Pink Houses, a large public housing complex in the East New York neighbourhood of Brooklyn, NY. The complex is named after Louis Heaton Pink (1882–1955), a former Chairman of the New York State Housing Board who advocated for public-private partnerships to combat poverty in black communities.

→ After decades of providing affordable housing to low-income New Yorkers, especially communities of colour, in the early 2000s the New York City Housing Authority began to defund the Pink Houses, along with its other properties, which resulted in a steady degradation in the quality of life there, including but certainly not limited to diminished upkeep, such as providing heat and hot water, as well as maintaining well-lit public spaces.[4] Upon shooting Gurley, Liang claimed that broken lightbulbs were a factor in why he had fired his gun – that he had not been able to see well enough to determine who else was in the stairwell and so had fired in defence.

The letters that make up this project are directly addressed to members of Asian-American communities who, in the words of the letter-writers, want officers such as Peter Liang, as well as Tou Thao, the Hmong-American police officer who stood by while George Floyd was murdered, to have the protections of white supremacy. These letters are continuously updated to reflect shifts in the terrain of protest – in other words, responses to more black bodies being murdered on US streets – but are also tailored to specific geographic locations and community histories concerning anti-blackness, including public health and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on black and indigenous communities.

Initially, when I planned the writing of this piece I thought I should include the English-language version of the most recent letter, but I am going to omit that in favour of encouraging the reader to seek out the letters on their own, especially since they are available in at least thirty different languages, as well as a range of contexts with regard to histories of black-Asian relations in disparate locations across the world: www.lettersforblacklives.com.

Case Study 2: F!, BLM Solidarity Video

In late July 2016, the Swedish → feminist political party F! (Feminist Initiative) produced a Swedish language → solidarity video intended to illustrate the fact that “the Swedish feminist party stands with Black Lives Matter… Feminist Initiative challenges the national self-image of Sweden as an equitable and open country that respects human rights”.[5]

The video features a number of black Swedish activists, writers, and public intellectuals, and each speaker contributes to the video’s overall analysis of anti-black expressions of empire and colonialism in the US and Europe, drawing analytical connections between black bodies shot on American streets and black and brown bodies drowning in the Mediterranean. The video argues that the diminished value of these bodies is acutely visible in the intersecting transhistorical logics of colonialism, empire, and contemporary racial capitalism, rooted in the transatlantic slave trade and European colonialism, and articulated vividly in the video’s comparative analyses. In particular, the scene and event of transoceanic passage is repeatedly evoked in recursive transhistorical reference to the Black Atlantic. And, throughout, the phrase “Black Lives Matter” is spoken, slowly and emphatically, in English.

I have written elsewhere about how the slowing down of the phrase in itself can be seen as a form of translation, but also of the problems which arise when English is both a language of anti-racist solidarity but also frequently an instrument of social death.[6] Furthermore, it is my belief that actually having to wrestle with the translation of a phrase such as “Black Lives Matter” forces the translator, and reader, into a closer relationship with the histories and presents at stake – that translation moves translators into more intimate relationship with what is said, including positions of → vulnerability and accountability, but also possibly forces a more corporeal engagement with power and privilege. Simply put, that translation can render seemingly distant structures – belief systems, histories, power structures – more emotionally and politically acute.

Four years later, during BLM protests in Stockholm in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, I read the comments section on the website of Dagens Nyheter, one of the two large Swedish daily newspapers. The article in question described that day’s protests in the city, and a group of commenters is concerned that more than 50 people have gathered outside to protest.[7] One commenter replies in defence of the fact that the group was in excess of the 50-person limit prescribed by the Swedish public health authority, but concludes his comment with the following statement:

However, one thing that struck me from the images is that they had the exact same signs as in the US. In English. If protesting against racially motivated police violence in Sweden, couldn’t they have taken the time to come up with their own signs?

Figure 2: Print screen of comments section from Dagens Nyheter, 9 June 2020.

How, why, and by/for whom is social death translated between languages and contexts? And what must be translated in order for the ontological death (see Patterson, Hartman, Wilderson) ascribed to blackness to be translated as clearly here as it is there, not through seamlessness, but through an attention to jagged edges, charred remains, and, perhaps, black futures?[8]

Case Study 3: Glossary of Common Knowledge / Solidarity in Translation

My task is to prepare a 10-to-15-minute Glossary seminar presentation on the term translation. The slideshow I put together ends up containing images taken from Letters for Black Lives and the F! solidarity video as well as a Reddit post about translating BLM to Vietnamese and the aforementioned reader comment from Dagens Nyheter. Due to the pandemic, our group – approximately 22 individuals spread across Europe – is meeting on Zoom.

My hope is to also conduct a very brief translation workshop where everyone, given the group’s linguistic → diversity, translates the same term into the language of their → choice. In my research, I have been conducting experimental translation workshops in Sweden, and the intention is to see what close readings emerge in the collective act of translation, in individual decision-making as well as in subsequent group readings, where we can examine resonance, slippage, imbrication, but also our own positions in relation to the scenes and events we translate.

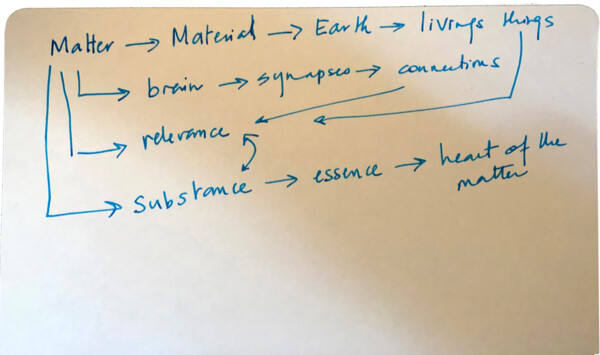

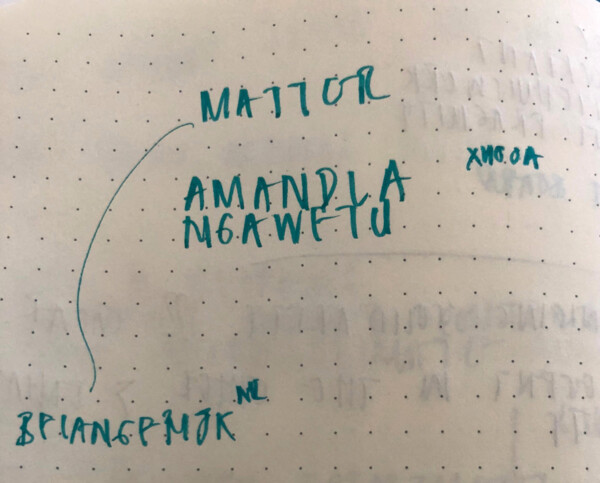

Initially, I plan to be as literal and linear as possible and ask everyone to translate “Black Lives Matter”, but as the seminar progresses, the exercise suddenly feels too clumsy and obvious, even brutal, and I realise that we will not have time to fully engage in the kind of close reading that the term, and translation, warrant. Mid-way through the three-day seminar, I decided that we should simply translate the word “matter”, and so we do.

Figure 3: Image of translations of the word “matter” from the short translation workshop during the online seminar of the GCK. Translations by Rasha Salti.

Figure 4: Image of translations of the word “matter” from the short translation workshop during the online seminar of the GCK. Translations by Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide.

I have thought a great deal about the implications of how we all translated this term, how we oriented ourselves politically and philosophically, but even more I have continuously returned to how I also felt the (Zoom) room shift as everyone set to work and, perhaps, had to turn inward and away from distant others. The “we” I use here to describe the “us” of that Zoom room seemed to take a different form – perhaps what I felt were generative fractures – once the task of translation was introduced. We, are a multilingual and polyvocal group, representing a range of explicit commitments to the interrelationship of art and politics, yet I would say that for myself, the moment of working with our linguistic heterogeneity was the moment when I felt the greatest sense of camaraderie, or affinity, with everyone there.