The reflexive museum

© Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow, 2016.

What would it mean to develop a reflexive museum? By this I mean one that is responsive to the social, political, and cultural context in which it functions, as well as to the historical precedents of 19th and 20th century museums.

The term is borrowed from social theory, where concepts of reflexive modernisation (Ulrich Beck, Anthony Giddens, Scott Lash) suggest that, as a result of the gradual disintegration of “simple” modernity – namely the institutional structures of industrial society such as civil rights, universal suffrage, public education, health care, the welfare system, and so on – a process of “modernising modernisation” is taking place. This relates less to “self-reflection” than to a “reflex” – an action that is performed in response to a stimulus – which arises through alienation from the impact of previous → bureaucratic systems.

As opposed to “post” modernity, reflexive modernity is based on the notion that modernisation is not yet over. Instead, it is evolving: through societal changes brought on by the fruition of modernity’s so-called ideals; in the face of transnational forces such as corporations and NGOs; and through the rise of individualisation as traditional forms of → solidarity [→ solidarity → solidarity] – such as political, religious, or → family ties – collapse. This is happening in part because of economic and cultural globalisation and also as a result of the liberation of → agency from modern institutions as they begin to fail the populations they were established to serve. In this gap, people are initiating alternative structures to circumnavigate the hierarchies of power and harness a surplus of human resources. The resulting new social movements operate alongside the mainstream configurations of modern society, often relating to global issues – from, for example, ecology to civil rights – on a local, networked basis.

Photo: Kate Fowle, Beijing, 2009.

To consider reflexivity in relation to the museum, it would follow that new formations would acknowledge shared genealogy with the 19th and 20th century Western, modern, public art museums: as instruments for democratic education; for cultivating the masses; that care for public collections (19th century.); as places for connoisseurship, specialisation, and discourse; as laboratories for experimentation; and as vehicles for visual spectacle (20th century). But these would be understood as key traits of the “simple” museum. It would be recognised that some functions are becoming obsolete, or being exploited, but that in its overarching purpose the museum is not yet exhausted, or satisfactorily replaced in society: there is no post-museum.

Philippe Parreno, Marilyn, 2012, © Garage Museum of Contemprary Art, Moscow, 2013.

Logically, the reflexive museum would be created by those who no longer feel beholden to traditional institutional mechanisms: who feel at liberty to be receptive to the → constituencies they operate within. They would focus on addressing issues of national and international relevance locally, while building → networks and → collaborations with like-minded organisations around the world. They would not be bound to larger state or federal mandates, drawing on infrastructural and financial resources that support the particular intentions of the museum. Driven by the impetus to be flexible and proactive, their form of governance would be reflected in the diversity of the workforces who produce the programs.

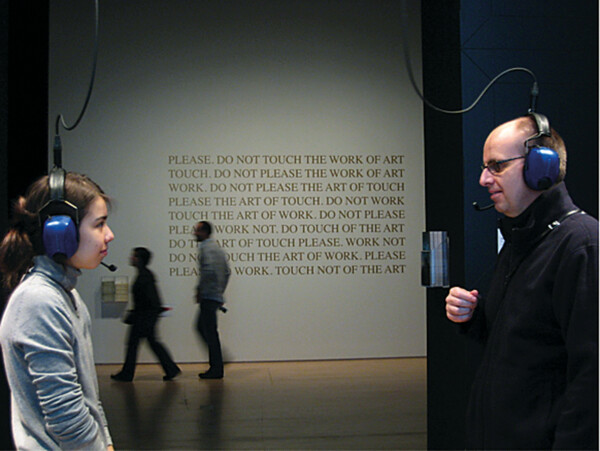

The Art of Participation 1950 to Now, Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, November 2008–February 2009 Installation view: Raqs Media Collective, Please Do Not Touch the Work of Art, 2009 and Matthias Gommel, Delayed, 2009 Photo: Kate Fowle, San Francisco, 2008.

Where the term “new institutionalism” gained traction at the end of the 1990s and early 2000s, as a way to describe the re-shaping of (mostly northern European) kunsthalles and how they could transform the production of contemporary culture for small, specialised → constituencies, the reflexive museum operates with a broader public in mind. Through the impact of globalisation, as infrastructures in emerging art world geographies shift from the biennial model to the institutional, the reflexive museum is a cogent framework. Untethered from Western traditions and assumptions, it is free to borrow from, mix, or regenerate all previous museological configurations. In particular, by developing outside established art centres, in the outskirts of Western culture, it can more readily adapt to the outcomes of deterritorialisation (Deleuze and Guattari) to reflect the new sense of conjoined cultural proximity and distance.

Unlike the late capitalist museum – with its emphasis on scale, spectacle, interactivity, and entertainment (weighted in history) – the reflexive museum – as a 21st century mode of modernisation – operates fluidly within the present stages of technosocial evolution. As such, social practices – which increasingly influence and drive the museum – will no longer be associated with the immediacies of context, shaped as much by processes existing in other places as they are in the local situation. Amidst omnipresent mediatisation, new imaginaries of the laboratory can be introduced: time and space become as malleable as our understanding of contemporary art forms in the re-evaluation of ideas and actions; pedagogy is dematerialised, while the pursuit and problematisation of objective knowledge – particularly in relation to overlooked or underrepresented phenomena – is reinstated as a meaningful endeavour. Through the reappraisal of historically-entrenched classifications and terminologies, the canon of art – as a Western construct – is challenged. By rejecting the influence of the inflated art market, what constitutes a collection is reassessed, what constitutes value is questioned, what constitutes cultural authority is contested.