In Morte dell’Inquisitore, Leonardo Sciascia analyses something really interesting: the walls of the cells where the Inquisition would detain heretics. What strikes Sciascia is the multiplicity of voices taking ground on the walls of the cells of the Palazzo Chiaramonte, the Inquisition prison in Palermo, and the way in which words of desperation and fear, awareness, and pray, irony and remembrances, together with the images of saints, allegories, and dreams, constitute the most “living and direct” testimony of the experience of the Inquisition.

This composition of voices, languages, and signs inscribed on the walls of the cells is the counterpart of the records of the Judges. The rumours of the cells against the discourse of the palace, paraphrasing Ranajit Guha. The inscriptions on the walls are a living testimony of an institutional narrative. Documents that live on the margin of oral history, that inhabit an informal and unrecognised surface of expression. Sciascia refers to this composition of words and languages as a palimpsest, referring to the classical definition of a document on which many layers intertwine, rather than one where discourse is linear.

In the cell of the total institution, the traits are the imagination of another life beyond the institution, beyond the wall. By inscribing, accumulating, overlapping and contrasting words and signs on the same surface, a silent conversation emerges between the one interned now, the one that was here before, and the one that will be here again after you: this silent conversation allows the inmate to become a living agent in and against an endless and identical repetition of objectivation that the institution imposes on you through confinement. A palimpsest of survival.

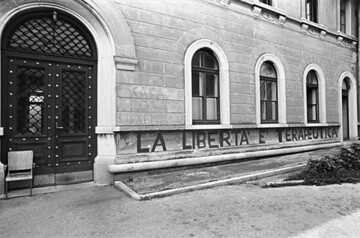

Figure 1: Ugo Guarino, Non abitato (Not Inhabited), graffiti, 1977.

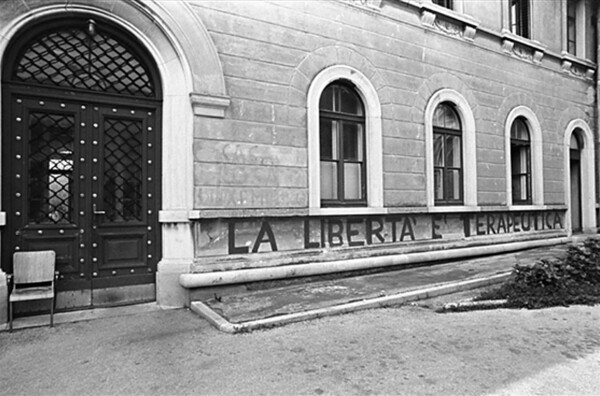

Figure 2: Ugo Guarino, La libertà è terapeutica (Freedom is Therapeutic), graffiti, 1977.

I want to translate this approach to another epoch, another wall, and yet maintain my focus on the way in which a multiplicity of signs on an unrecognised surface permits us to grasp a subaltern expression. The palimpsest of written words and signs on the walls of the former Psychiatric Hospital of Trieste, the first to be dismantled and closed in Europe. These graffiti are part of a wider artistic collective practice that contributed both to the critique and invention of new institutional forms in the Italian psychiatric radical movement since the 1960s. (Figures 1 and 2)

Throughout the deinstitutionalisation of mental health care in Trieste, another cry appears on the other side of the wall: “Freedom is therapeutic”. The graffiti inscribes a new sense of mental healthcare based freedom and care instead of violence, negation, and segregation. It is a line from Franco Basaglia, the new director, who has contrasted this with the ergotherapeutic discourse of traditional psychiatry, affirming a different logic of care. After the liberation from the asylum, the palimpsest of survival invades the city. A palimpsest of the commons.

Franco Basaglia is the initiator of a radical reform of the psychiatric practice, that moves step by step, from the dismantlement of the mental asylum towards the reorganisation of mental healthcare as a series of services, facilities and resources of support that intervene in the complexity of social life and construct the project of care around and with the user. The deinstitutionalisation of the asylum is part of a bigger picture: a critique of medicine and of the welfare state. The welfare state is a prescriptive device to organise social production, and the technician is a functionary of oppression that divides the sick and the sane, the productive and the unproductive, the citizen and the outcast. The radical practice of healthcare involves not only a different understanding of biomedical practice and of public health. The crucial element is the invention of new institutions: the definition of a different organisation of care that puts the technical practice of welfare in the complexity of social reproduction, as a political dynamic of social change.

These inscriptions in the city make visible another understanding and another practice of care to the many: one based on the production of public services of support that guarantee a “constitutively difficult freedom” of the frailest and the less recognised citizens of Trieste. The multiple and unfinished expression of the palimpsest is in a permanent tension with another “grammar of space”, the one that the Basaglian movement produces in order to legitimise the radical institutionality of Trieste. In this movement of invention and regulation, the palimpsest contests and opens the closed logic of the institution, affirms the possibility of a common speech, produced through a collective use and a collective practice of inhabitation. The possibility of inventing new institutional devices and new rules depends on the disruption of this static grammar, upon the permanent disarticulation of the institutional tendency to repetition, upon the rise of a continuous invasion from the outside towards the inside. The palimpsest contributes in producing a common speech, configuring a blurred urban space where the language of the institution lives with the language of the city.

Figure 3: Ugo Guarino. Photo: Emilio Tremolada. La verità è rivoluzionaria (Truth is Revolutionary), 1977, 2015.

With its constant inscription in the everyday life of the city, the palimpsest does not determine a solution, rather it rekindles an affection on which to hold and institute something new: care as a common, as a collective practice of social reproduction, contrasting the privatising tension of neoliberalism, reconfiguring the protocols of the services, and contesting the grammar of the institution as a language of exclusion. The signs of the palimpsest do not constitute a discourse to be defended – the one of the prescriptive function of the welfare state – or, in contrast, to be dismantled in the name of an entrepreneurial neoliberal logic of governance. It rather permits us to inscribe the memory as part of the contemporary and to care “in the wake of the crisis”. The walls of the city constitute a palimpsest where a common speech can be produced and reproduced, affirmed, contested and negotiated every day. These expressions are the constitutive ground for a space of possibility of the urban commons. (Figure 3)