To think about → constituencies today is fundamentally to think about power in the framework of liberal democracies. So arguably the first mistake, in our view, one could make when leaning on the subject is surely to fail to understand this framework as an historical and → situated social construct. We often tend to refer to our political concepts, like democracy or constituent power, from an ahistorical perspective. Crystallising both ancient and modern archetypal forms of political organisation (Greek democracy) or shifts in the power structure (the English, French or North-American revolutions), it seems that our political horizon is, at best, represented by a sort of utopia toward which we fight, time after time. This linear approach needs to be challenged again.

The Espectros de lo Urbano project understand urbanity as the “constant and ever changing relationship between capitalism and the territories it encompasses and utilize”[1]. Embracing this definition helps realise the fact that urbanity is not limited to the dense cities and hyper-centres of the globalised world, but encloses all spaces and territories involved in a systemic, structural relationship of power: the urban matrix. In this sense, urbanity can be seen as the major production of our modern system. It is at the core of the colonial expansion and the more recent “globalisation”, to mention only two of the most obvious examples. Urbanity mainly defines the historical process of the modern world system as a question of territorial expansion. It is then the primary framework through which we can understand the social production and reproduction of our system, historically and spatially situated.

The second and major consequence of the urbanity approach as a systemic framework is that Western epistemology and its evolution, the body of modern knowledge (science, legality, languages, etc.), needs to be understood as responses to the cognitive needs of the spatial and territorial expansion of modernity, and all the possible post- that have followed it.

We believe that the democratic forms as we know, speak of and practice them are deeply embedded in the urban matrix. They historically respond to its need and agenda, across time and space. Hence we always need to understand where we stand now, and account for the past, when we start a conversation about political power and its constituencies.

We propose an analogy between democracy as a politic form and the museum as a cultural institution, understanding that the main link between the two is the nation state.

The spatial expansion of our modern system has produced epistemological necessities leading to the emergence of the modern cultural institutions. The infinite moves and redefinitions of power relationships cutting across all territories have been absorbed progressively by the capitalistic system as shaped political organisations and struggles, leading to the prevalence of the state as its principal form for the dominant, centric territories. On the other hand, we understand the museum as a response to the cognitive needs of the nation state, which in its turn responded to the cognitive needs of urbanity in modern history.

It seems logical to draw a red line linking urbanity to the nation sate and finally to the cultural institutions. We hope this genealogy serves as a fertile ground in order to redefine a proper basis when speaking of constituencies and what his could mean for the museum.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall in the 1989, and along with the strengthening of capitalism in its neoliberal form, a half-hearted view of “capitalist realism” (to which “there is no alternative”) was installed in the West, which has led to a weakening of social movements and democratic institutions themselves at the hand of financial capital.

However during the last 30 years, in that same horizon of “impossibility”, more often, in many places and most of the time situated at the edge of the Western-centred world system, we have witnessed the consolidation of new models of constitutions and political forms (Zapatism, Rojava, Bolivia, Chile, etc.). Each of these are specific – and different – examples of the redefinition of the political, via profound work regarding the fundamental legitimacy of the constituent power. They give a clear relevance to the notion of territory: nature’s rights, the common management of its resources like water, and a plurinational approach, are only few examples of the importance and particularity of this relationship with their land.

We propose the term Territory as an opportunity for the museum to resonate with another conception of the constituency of power (away from the sequence Bourgeois Revolution → Nation State → Cultural Institutions), moving toward the fissures appearing at the edge of our democracies, where new forms of the political are emerging. Paying close attention to the emergent political forms that are today challenging the nation state where it is fully stressed by its internal contradictions should inform us about a multitude of political imaginaries, much needed if we want to escape the urban matrix contained in our very notion of culture and its role in the political sphere.

January 1, 1994, was a very particular beginning of the year (or end of the previous one). The EZLN (the Zapatista Army of National Liberation) appeared on the scene, and with it an enormous territory that seemed to no longer exist had raised its voice: one that had been silenced, ignored and despised for centuries. It opened a global possibility to rethink our relationship with others, with the human and non-human, as a political power.

In that same year, the Mapuche Movement made itself heard with force in a Chilean transitional framework that had betrayed the desire for change after the end of the civic-military dictatorship. The ties that the agreements among the liberal sector, national and transnational businessmen and the pro-dictatorial right wing had agreed, far from curbing the model of dispossession that neoliberalism had installed, instead exacerbated it by accelerating the process of modernisation: a total privatisation of public services. The Mapuche Movement began to speak about the right to the land, and not from a productivist point of view, but from a deep understanding that a territory that is inhabited is a constitutive part of those who inhabit it. They are fighting against a hydroelectric plant that seeks to flood their lands in order to extract value, because of the constitutive nature that this territory means for them and their lives.

In another territorial space, since the beginning of the 21st century Kurdish women from the diaspora, and mainly in Syria, began to organise themselves into the Women’s Protection Units, better known as the YPJ, embracing a democratic confederalism that has allowed, together with a huge movement of communities, peoples and nations in the same territory, a multi-ethnic, multi-religious and peaceful coexistence. In Rojava (northern Syria) innumerable peoples and nations coexist, such as the Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians, Turkmens and Armenians, Chechens, Circassians, Muslims and Christians and Yezidis and other Syrian religious communities, together within an autonomous administration that ensures gender equality, decentralisation, → ecological development, and tolerance of → diversity in all its forms.

The constituent constitutions

The search for transformations in some → southern countries has led to debates about the formal framework of democracies. The constitution as a governing body of the democratic framework has begun to be questioned, fundamentally due to its universalist nature and limiting vision. Already in the 1990s several Latin American countries were going to carry out processes of change, but it will be during this new century when deeper processes will take shape in territories as diverse as Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia and Chile. These last three are a clear example of how to rethink and position the democratic logic linked to the territory, with constitutions shaped from the territory.

Ecuador declared itself a plurinational state in 2008, beginning a two-year process through a Constituent Assembly, and has ultimately produced a new constitutional text. This Constituent Assembly defined the Ecuadorian state as plurinational and its purpose is to implement sumak kawsay (kichwa) or good living, which is a political proposal that aims to achieve the common good for people in accordance and harmony with nature and sustainable development.

In 2009, Bolivia began to create its new constitution, which declares in the first instance that it is a political constitution of a plurinational state, and in the same way that Ecuador plans to implement sumak kawsay.

The plurinational state presupposes political and administrative decentralisation, culturally heterogeneous and with the participation of all groups and social sectors. The plurinational state is opposed to the Napoleonic idea of “One Nation = One State”; concluding that “a Nation does not necessarily have to form its own State, but several nations can form a single State”. To this new administrative conformation, the Bolivian constitution also deepens the ways in which we relate to what surrounds us, how we engage with the territory in multiple ways. Thus the land, the territory, nature, the human and the non-human are central in terms of a mode of development.

Chile is currently undergoing a transformational process that started in 2019 and was triggered by a social explosion that has dismantled the fallacy of the neoliberal model as a model for development. The magnitude of the destruction of territories and bodies under capitalism in its neoliberal form is at the moment protected by the constitution, which was approved under the civic-military dictatorship. Thanks to months of social mobilisation, Chile is today undergoing a constituent process to create a new constitution. Like the previous examples, the first articles approved by the “Constitutional Convention” propose a plurinational state, which also embraces the kyme mogen (mapudungun), suma qamaña (aymara) or good living.

Façade of the GAM Cultural Center, Santiago de Chile, 2019. The personal archive of the authors Nancy Garín and Antoine Silvestre.

In the same way, it assumes the life and rights of nature, of the human and the non-human, as fundamentals, and places the territories and their diversities at its centre. The same thing happens in Colombia, where today it is possible to think that a woman with African heritage, and environmental activist and part of the communities fighting against → extractivism can preside over the government. Their way of living and building society, as well as the way in which the discourse is elaborated, collectively, radically confronts the forms sustained by the capitalist-colonial development models, where the importance of the territory goes beyond the material, where the territory is constitutive. Where the common projection and every possible activity puts life at the centre: “Our grandmothers taught us that the territory is joy and sadness, that the territory is life and life has no price, that the territory is dignity and this has no price.”

Constituent Body/Territory

In these views, the relationship with the territory or territories is not thought of as a productive way/material use, but as part of a whole of which we are part. Thus thinking/feeling as a body/territory, where rights go beyond what is human, where nature and otherness are consubstantial to us, where the very logic of territorial administrative ordering – as seen in the nation – goes through this dialectical relationship.

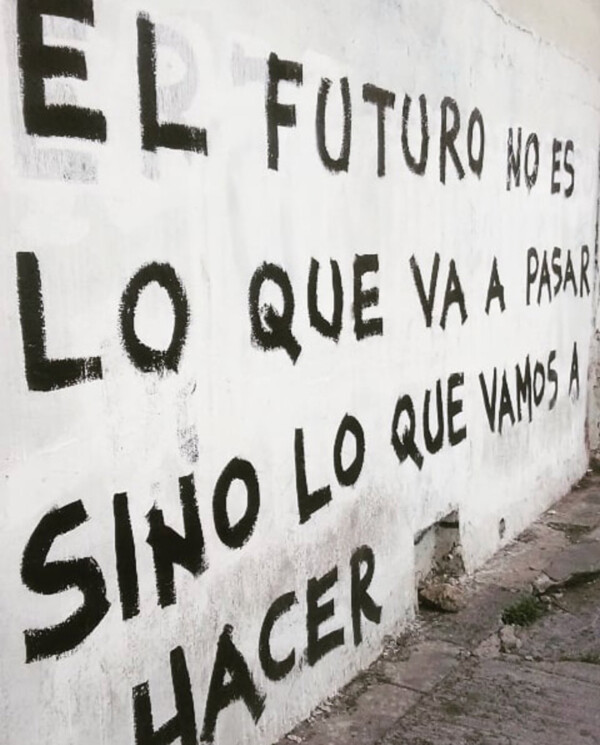

Graffiti on a street wall in Santiago de Chile, 2019, anonymous. Twitter link.

During the most critical months of the social unrest in Chile, the central spaces of the cities were intervened by hundreds of protesters, day and night. It is in these areas of the city that most of the art centres and museums are built. These spaces, despite the difficulties in the context of social unrest, joined the process by responding with their organisational operations and decision-making, opening their doors and becoming part of the territorial assemblies, supporting creative and collaborative territorial links with those who were part of that territory, as well as those who inhabited it temporarily during the demonstrations.

In turn, the symbolic outburst that was unleashed during almost a year of mobilisations, on the walls and streets of the cities, stirred up discussions about art and culture, as well as institutions. In this way, the borders of inside and outside were blurred, transforming the public space, the streets and territories, into an amplified museum.

Possible examples are the current project being carried out by MACBA under the direction of Elvira Dyangani Ose. The Museum of the Possible or The Possible Museum, as it has been called, seeks to temporarily interrupt the productive flow that the institution sustains, involving those who carry out the tasks of the institution, visible or not, to distort the habits and norms that have ceased to be questioned. From there, it allows and promotes the exercise of collectively thinking about other possible ways of doing. “The possible museum is also what can be done, the framework of possibility that opens up, but also restricts, based on what already exists. It is neither the avant-garde impulse to produce the new at the cost of rejecting the past, nor the conservative instinct to perpetuate what is given, but the affection with which one can take → care (→ care), of something to make it good and not only, nor always, to make it grow,” says Dyangani Ose.

Thus, this project territorialises its constitution in the museum institution itself, it is thought of as it constitutes itself, not from abstraction, but from its own body/territory that build it up and... constitutes it. Going from how the forms of work are organised, the administrative logic, internal work, remunerative rates, to why and in what way we inhabit that body/territory called a museum, which in turn is part of another body/territory: its neighbourhood, its city, its international connections, and its workers, its public, its political context, the local art scene, etc.

And perhaps these examples of reconstituting ourselves from that territory/body, to embody the territory in our practices, to inhabit it dialectically, are necessary steps that will help us energise one or many responses to the crisis of the cultural institution.