I walked into the rehearsal and it was obvious that they were taking a break. Brecht was sitting in a chair smoking a cigar, the director of the production, Egon Monk, and two or three assistants were sitting with him, some of the actors were on stage and some were standing around Brecht, joking, making funny movements and laughing about them.

Then one actor went up on the stage and tried about 30 ways of falling from a table. [...]. Another actor tried the table, the results were compared, with a lot of laughing and a lot more of horseplay. This went on and on, and someone ate a sandwich, and I thought, my god this is a long break. So I sat naively and waited, and just before Monk said, “Well, now we are finished, let’s go home,” I realised that this was a rehearsal.

This is how Brecht’s assistant Carl Weber described his first rehearsal visit to the Berliner Ensemble and his contact with the artist’s creative → process.[1] Rehearsal work under Brecht’s direction was characterised by a conscious subversion of time economies.

According to Annemarie Matzke, Brecht’s rehearsal time is above all time spent together, which seemed unlimited. At first glance, Brecht’s work on rehearsals can thus be described as undermining a traditional approach to the creative process in the theatre: the rehearsals for a mise-en-scène usually have a concrete performance and premiere date as a goal; they require making appointments for working times; they are frequently organised around a detailed division of labour; and tied to a common rehearsal location. The participants are connected by means of contracts. Investments of time and money are needed, which create respective dependencies. To this extent, every rehearsal practice is always working on the institutionalisation of its own activity at the same time.

In Brecht’s practice, instead of solidly planned rehearsals, there is an indeterminacy to the situation that seems to be an attempt to avoid the compulsion to create. Time spent together, which seems specifically unplanned and uncontrolled, is emphasised. The hierarchies of production (the division of labour between director and actors, assistants, and dramaturgs) disappear in the atmosphere of rehearsal. They seem to be friends interacting with each other rather than colleagues working together.[2]

The anecdote of the encounter with the rehearsal as a break, as narrated by Brecht’s assistant, can serve us as a metaphor and starting point for considerations about the methodology of rehearsal in the context of the visual arts. To do so, it will be necessary to look more broadly at the significant transformations that have taken place in the visual and performing arts since the 1960s until the present time, which have led to a fundamental paradigm shift.

Today, we no longer view an artwork as a static object defined by a single prescribed meaning that is communicated to a universal viewer. According to the art historian and theoretician Amelia Jones, the notion of performativity highlights the open-ended interpretation of an artwork – which must be understood as a process.

Performativity enables the process of reinterpretation and revision of discourses, artistic practices, and artworks. Such a critical strategy offers the means to open up the possibilities of reception, through multiple readings of one work, which introduces the possibility of ambivalence, confusion, subversive, and non-normative interpretation of artworks, collections, and archives.

The phenomenon of performativity is also associated with distinct systems of production and labour, models of collecting, and a type of institution that is different from previous, traditional institutional models. The new type of institution should be based on a methodology derived from disciplines other than the visual arts. Contemporary artistic practices and time-based media require innovative strategies and production systems.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, key to the development of both theatre and new forms of performance art was the phenomenon of postdramatic theatre, which put aside the importance of the text and the relationships among characters in favour of developing connections between what happens on the stage and in the audience. Although there is an ongoing debate about this notion among theatre researchers, Bertolt Brecht’s ideas about political and experimental theatre have undoubtedly been highly influential in forming and developing many new theatrical genres, including the process of creation, rehearsing, and the way the audience is assigned an active role in the production and interpretation processes.[3]

In the context of contemporary art strongly influenced by performative practices, the rehearsal is becoming a different way of approaching research-based projects and exhibition spaces. It is evolving into a very relevant format in the context of time-based media such as performance. The methodology of rehearsal in the visual arts has its own characteristics, and these might be different from those found in the context of theatre and dance.

The process of rehearsing in classical theatre aims at perfection and virtuosity, whereas in contemporary art it appears as a contradictory model of practice where the final outcome is open, improvisational, and dialogue-oriented. The methodology of rehearsal introduces innovative labour structures and productivity. What does this mean for institutions, audiences, and cultural workers? Does rehearsal hold a transformative power; does it constitute a risk for institutional stability?

The concept of rehearsal is important in the context of many contemporary artistic practices, especially those that have a hybrid nature and combine visual arts with performance, such as Cally Spooner, Falke Pisano, Zhana Ivanova, Emily Mast, and Catherine Sullivan, to mention just a few.

The Spanish artist Dora García has made rehearsal one of her essential tools. The artist has used the rehearsal format in several of her projects, including at the exhibition dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel in 2012. Her performance, titled KLAU MICH, was a television project released in collaboration with Theater Chaosium and Offener Kanal Kassel, and it lasted 100 days, which was exactly the duration of the exhibition. The project took the form of a live TV programme in which the audience could participate. The programme was also broadcast by a local station in Kassel. The concept of KLAU MICH originated from the idea of a “dress rehearsal”, i.e., a rehearsal which takes place just before a premiere, where the director can still make changes to the materials before the work is officially presented, when the audience can still influence his work. Whereas Dora García seeks to enable an active role for the audience, she perceives the idea of a premiere as a situation where the audience gives its verdict and, in a sense, decides what is “good” and what is “bad”. As the artist states:

Quality is not universal. It depends on many things, notions of social class, backgrounds of the public, some things are successful with certain public and other things are not. I have a problem with the notion of success and with the idea of success connected with performance. [...]

I also think that it completely takes away the joy of performance when there are so many factors depending on the approval. There is something satisfactory about permanent rehearsal. When you work on the performance and you work towards the premiere, the premiere has a very precise time frame with people and ceremony created around the work [...] In Kassel we had this very beautiful stage design. There was always something to see but we were not performing necessarily for the people who came. [...] It became a durational performance; people could come when we had a coffee break or warm up exercises.

In another work entitled Rehearsal/Retrospective (2010), the artist again uses theatrical means of expression, referring to the convention of street theatre. The duration of this work is flexible and depends largely on the museum’s audience, and it is usually an unannounced action. There is a coach who is instructing the performers, spontaneously “correcting” their repetitive actions. For example, the coach comes and asks the performer to repeat something louder, so that the performer may change the tone of their voice. The work is called Retrospective because it brings five different works by García together. In the Reina Sofía Museum, in Madrid, the performance started at the entrance where visitors were queuing for their tickets. There is a paradox in this work: the public is watching a rehearsal and, at the same time, a theatrical performance that follows the tradition of street theatre.

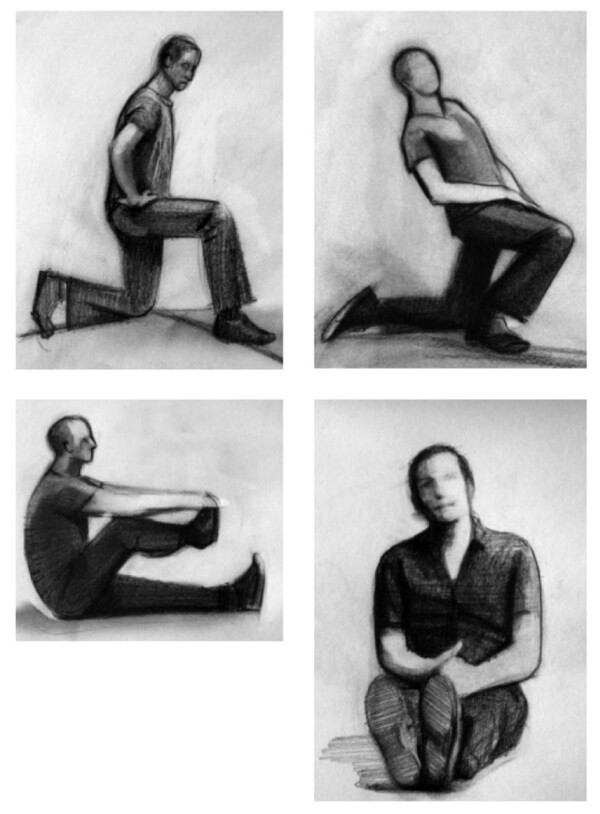

The Sinthome Score (2014–16) (Figure 1 and 2) is another work that also takes the form of a rehearsal: something in between a seminar and an open class. García takes a fragment of Lacan’s Seminar XXIII and performs the text between a “reader” and a “mover”, between body and language. The aim of the performance is to study the text, which speaks precisely about the idea of practice that saves us from falling into madness. Performers can invite the audience to step into one of two roles of “reader” and “mover”, determined by the principles of the performance.

Figure 1: Dora García, The Sinthome Score, 2013, performance, score, installation, Ellen de Bruijne Projects, 2014. Photo: Ellen de Bruijne.

Figure 2: Dora García, The Sinthome Score, 2013, performance prop, score original drawings by Dora García.

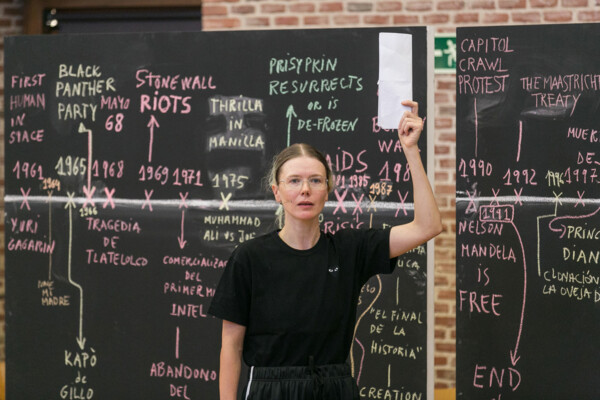

A work by Dora García, titled The Bug, (Figure 3) is a performance adaptation of one of the last science-fiction plays by the futurist Vladimir Mayakovsky. The piece was created in collaboration with Oslo Art Academy, M HKA, and De Singel in Antwerp, and, again, it has a similar structure to an open rehearsal. It reflects on the notion of cyclical time and the dimension of revolution directly connected to this concept, based on the assumption that history moves in cycles and there is always an eternal return. The participants in the project aim to reconstruct contemporary history using timelines written with chalk on → school blackboards which are part of the scenography. The methodology of open rehearsal helps to create a new work based on the performative installation. The development of the project aims at studying and understanding collectively created and performed theatre, forming a group made of different ages, experiences, and disciplines, with no clear division between audience and performers.

Figure 3: Dora García, The Bug (After Mayakovsky) [El Bicho], collective performance, October 2022. Krõõt Juurak in the image as a performer. Photo: Estudio Perplejo for El Amor / Centro de Cultura Contemporánea Conde Duque.

The formats of the durational performances that Dora García develops vary from open rehearsal to open class, or live broadcast TV programme. They function as a critical tool to alter the perceptions of the participants as well as to build political awareness. Paraphrasing Donna J. Haraway’s “→ situated knowledge” concept, we can say that working with improvised actions in this manner is a way of engaging with thinking as a process. It is less about dealing with fully resolved problems and more about experiencing the movement of thoughts in uncertain circumstances. This way of working relies on the freedom that emanates from such a process, and the acceptance of the fact that such a method may be chaotic and never final.[4]

As we have seen during this presentation, the concept of rehearsal in the visual arts often becomes a tool for questioning the foundations, routines, restrictions, limitations, and instrumentalised genres introduced by institutions. It represents zones of transition, collective agency and authorship, and different relationships. It becomes a means for collective formation. In contemporary artistic practices, rehearsal as a methodology serves to develop new modes of production and spectatorship, whilst at the same time it constitutes a challenge for the institutions that host them. Hopefully the format of rehearsal and open-ended artwork can influence the transformation of existing models of museums as spaces of preservation of objects. This collective, inclusive way of working brings new agency to art institutions. On the other hand, we must remember about the new forms of labour that the presence of the body in the space of art requires. One may ask, how do we keep these works alive and meaningful? What is the role of the spectator? Who shows what? Who may speak? Who may make judgments?

And finally, can we afford to take a break and spend time together?