Porosity, as a conceptual frame through which to think constituencies and the museums they occasionally come into, is appealing. I’ve been thinking about porosity a lot of late, particularly in relation to how it allows educational projects out of the bind of an either-or relation to institutions and communities. Porous projects might allow us – the us of (temporary) discursive positions – to pursue methodologies that leak, lean, drift alongside the practices they seek to follow.

But I’m also mindful of what appeals. Appealing proposes a possible intimacy in the same way that porosity allows our conceptual lenses to focus only on where things do or can or are permitted to leak. This focus blurs or elides the structural logics of the sieves and skins of separation. Particularly in its metaphorical usage, where the museum might seek to be porous to the contemporary moment or its constituents’ interests, there is the risk of a slippage away from existing socio-political realities and relationships (how much is already structured into a relational history and mutual practice of presumptive identification?), and the implicit limitations obscured under these gestures of openness (is the museum willing to be so porous that it dissolves itself?). We need to attend to what precedes a proposition of porosity.

The structural logics of who or what is porous, when, and to whom, function to give form: an inside and an outside become presumed in the processes of collectivising and abstracting complex subjectivities and histories into sites through which the porous moves and takes direction. Skins of separation function as protective and sustaining – coalescing into a group is a means of coming together, of creating an ecosystem of coexistence based on shared identities or practices – but they also contain and separate, particularly when propositions such as porosity premise themselves on inviting in, rather than reciprocal (partial) dissolutions. That is to say, there is a power and positionality involved in these propositions and in the material they offer or restrict, that need to not get lost in the leaking.

The concept of porosity is mainly traced back to the 1920s and the field of what we now call urban studies. Walter Benjamin and Asja Lācis, in their essay on Naples in the 1920s, conceived of the city as porous to its inhabitants’ use of it: “Building and action interpenetrate in the courtyards, arcades, and stairways. In everything they preserve the scope to become a theatre of new, unforeseen → constellations.”[1]

This sounds familiar in its idealism. The idea of constellations and of the museum as a potential site for interjections and interventions, finds historic echoes in Benjamin and Lācis’ conception of the interpellated usages of city architecture and the fluidity between private and public spaces in Naples. But their porosity is only present-tense; premised on an extant history (the buildings already exist). The poverty of “the most wretched pauper”[2] they describe is not affected by the porosity of their relation to the city. The structural logics of their lives go unchanged despite these proclaimed permeabilities.

Their sense of the porous is the constantly improvised, changing relation between people and places: a negotiation at once playful and timeless. For Benjamin, Lācis and Ernst Bloch, who subsequently draws porosity out into a master concept for Italian culture more widely, the appeal of porosity might lie in its sensuous antithesis to the “reified character of modern capitalist society”.[3] We might rephrase that to navigate the appeal it continues to hold for us – as an antithesis to the reified, historically constituted realities of the museological domain we are seeking to, and indeed invested in, undoing or expanding beyond.

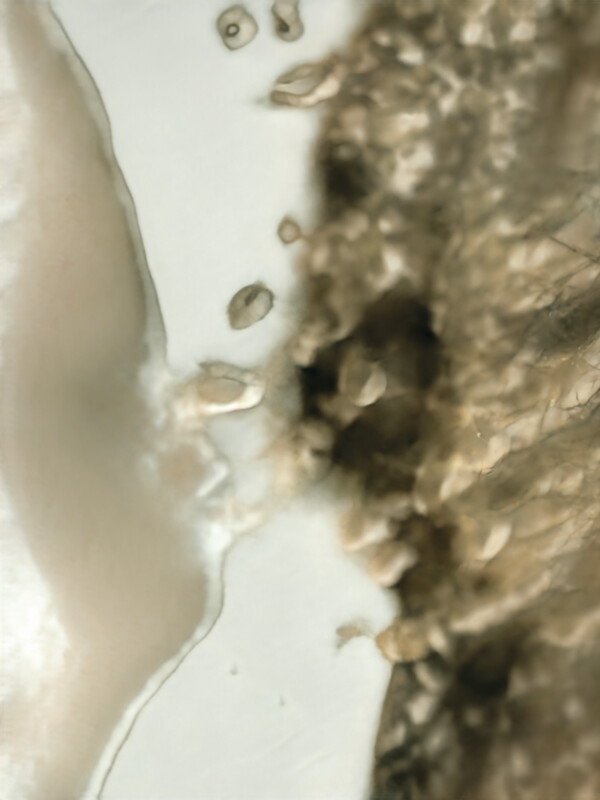

Juliette Pénélope Pépin, Gerridae, 2022, AI-generated assemblages.

Juliette Pénélope Pépin, Gerridae, 2022, AI-generated assemblages.

Juliette Pénélope Pépin, Kinspore, 2022, AI-generated assemblages.

Juliette Pénélope Pépin, Polder, 2022, AI-generated assemblages.

Juliette Pénélope Pépin, Strait, 2022, AI-generated assemblages.

Gerridae – Kinspore – Polder – Strait is one of the results of a long-lasting series of thought exchanges between Sophie and Juliette. Using Sophie's text, and memories of previous discussions on ponds, porosity, polders, fluidity and wet matters, Juliette created a series of digital collages. The images employed to form those assemblages were generated with an AI trained on several databases of polders, ponds, skins, membranes, and sea sponges. A process that in itself led to another porous exchange between Juliette and Sophie. Sieved through the process are these images.

Juliette Pénélope Pépin is an artist whose messy practice investigates human and non-human perceptions: their phenomenology, mythology, and technological frameworks. Through installations, videos, images and speculative narratives, J.P. examines the meanings of «seeing» and «being seen» in our time. Concerned with our current epoch, she values and develops participatory, discursive, and negotiable art projects.

I want us to shift from the possible theatricality of porous sites – their ability to function as stages offered up to both the pauper and the poet – to why it appeals to frame our sites as such, and, vitally, what our stakes in that appeal are. When thinking of and around constituencies, and their relations in/of/as/with/nearby the museum, we need to reflect on our existing → situatedness, agency, power, commitment and interests in doing so. To think of the porous as empowering, which both urban studies and museology seem want to do, is contingent on who initiates and who consents to the porosity presented or requested. It is from this line of thinking, or perhaps even, to continue loosely allowing other references to seep into this text, this line of flight,[4] that I come to a term that could be used as a thread when thinking through constituencies and the possible porosity of their interactions with museums.

This term – in/vesting – is an intentionally weak one, more of a method to approach thinking than a definition of a practice. In/vesting seeks to unfold how one is already implicated, to sense check where, how and for whom porosity intermingles with power, positionality and politics, and from that position, how one can build out structures of facilitated, considered and contingent porosity.

In/vesting

The enfolded meanings of investing are pertinent in the context of museums, where involving constituencies may relate to multiple objectives and goals. Both the contemporary both-ways cut of investing – where money or time is put into something with an interest both in the thing itself and its subsequent return for the investor – and the historic meaning, in which investing refers to clothing or surrounding something, might offer us lines (of flight) into thinking along the skins of our desired porosity.

Investing as the clothing or surrounding of something, whether for military purposes or to endow someone or thing with power, defines that which it clothes or surrounds by means of its capture. So too, thinking about the messy range of people that interact with museums as constituencies, functions as a means of identifying, of grouping for purposes or intents that might curtail the self-definitions or dissent within these groups. Categories are functional, but that is not to elide their implications: the defining of constituencies, whether for conspiratorial intent[5] or otherwise, is a proclamation that positions both parties in a fixed relation a priori. Investing’s contemporary financial associations – a recloaking of one’s existing capital – are associations that might also allow us to remain critical about some (museal) practices of constituency engagement.

Inserting the slash as a moment of pause, a break that thinks along the lines of study and the undercommons,[6] is a proposition to think of in/vested as a future-oriented term: to think about the ways in which we might acknowledge power and positionality in order to become more politically proximate and co-constitute across institutional, representational and communal sites. This slash might function as a sieve or skin of separation, and steps away from the prefix-heady tendencies of current practices, where additive words don’t always undo the layers of meaning, histories, power and associations of the terms they appendage.

To hold the slash also allows for an orientation of involvement: the museum is not separate from its constituents. Yet, its embedded positionality is coupled to a vesting. Vesting in, or vesting with, refers to an endowing of authority: to give power or property. This endowing implies a directionality (a handing over, a leaking out) but also a position of pre-existing power (to be able to vest). What are the implications of having the power, from one’s position with-within-against (per BAK’s thinking), to enable the voice or involvement of others?

To speak nearby

“Can I apologise without asking for your forgiveness?”

— Cathy Park Hong, Minor Feelings [7]

There is a power involved in enabling, proclaiming or projecting the involvement of others; one implicates oneself and simultaneously positions the other. Trinh T. Minh-Ha evocatively suggests a practice of “speaking nearby” to desist from reducing reality to representation.[8] Her thinking, in turn, allows for a means of thinking away from a mode of → solidarity that risks slipping into assuming mutuality prior to acknowledging difference, distance and dissidence.

In affinity, Tim Ingold writes: “Whereas of-ness is intentional, with-ness is attentional”.[9] Contextualisation refers groups or individuals back to the intentionalities that presume to explain their perspective or position. Attending to, instead, allows for a futurity: a speaking-thinking-doing in step that gives space for a negotiation from the present.

It’s worth noting here, however, that I am drawing on the thinking of an anthropologist and a documentary filmmaker. Interdisciplinarity isn’t a given porosity either. Sara Ahmed, to yoke yet another formal field into this interpellated conversation, reminds us that attention involves a political economy.[10] Our attention is perpetually relative to “the ongoing labour of other attachments”;[11] each → choice to attend to something involving a process of intersecting priorities, energies, abilities and privileges.

What does a constituency thinking that operates a praxis of nearby, rather than a praxis of or for others, feel like, then? Part of that might involve acknowledging the limits of one’s ability to host, to become part of or intimate to practices. Part of that might also involve thinking along varying lines of temporal engagement and intensities: the museum as a node, sometimes a shell, sometimes a shelter, sometimes a resource. I am thinking of in/vesting as a gesture, an action. A surrounding that is gentle and temporary without being too vague or too inconsistent; an awareness that clothing cannot become skin.

To find one’s in and the power of vesting

Museums, if I am to temporarily inhabit the art historian explicitly, are sites of contestation: the civil and the civic, the represented and the representational. They come into estranging encounters that have only pluralised as remits, funding and ambitions continue to shift and be → negotiated, both from within, between and outside the museums themselves. At once an institution, a symbol of the (nation) state, and a collection of people and things. But museums are also very practically located, for the most part. One might think here of the Van Abbemuseum, with its long history in and of the municipality, and how it is situated in a specific political relationship. Yet there’s a layering of situatedness, too: museums leak out into, flow as part of and shift between global, translocal and local spaces in their material and conceptual programming.

These situated positions come into play with the differing relations and imbrications museums hold for those that interact with them. This situating in, which can also be thought of positively – one is situated, one has a web of networks, one is sited – leads to an imbrication that brings us to the skin of the matter. Following a loosely decolonial line of thought, these relations and the situated symbolisms of the museum cannot simply be undone through a museological shift in vocabulary or orientation. How, then, to engage in this choreography of re-negotiation, towards a more porous relation, without returning to a speaking of, for or over?

There is both a generosity and an oppressive relation entered into when holding or constructing spaces. This comes back to the skins of porosity: a fluidity is predicated on collective individual movement, which demands of each a willingness, consent and (→ rehearsed) ability to move. In educational spaces, be they museal or elsewhere, open, flattened hierarchies of learning are often perceived to be more equitable and thereby desirable. However, these modes of interaction, where circles are formed or people are invited to be listened to, are often underpinned by implicit rules of engagement, or are felt to function in these manners.

Further, there’s a reliance, if not a demand made, on the energy and input of those invited in, often on the presumption that this is energy and input they would willingly give. A pre-existing relation of power cannot be undone by offering the cloak onwards. What new streams of movement need to occur before one can be vested, as a learner, with this kind of participatory authority, and what streams of historic movement have already occurred under the surface of our opening up of spaces, that allow museums to continue to claim and hold the power to vest?

To maintain the break of in/vesting

“Politics proposes to make us better, but we were good already in the mutual debt that can never be made good. We owe it to each other to falsify the institution, to make politics incorrect, to give the lie to our own determination. We owe each other the indeterminate.”

— Moten and Harney, The Undercommons[12]

Moten and Harney speak of the break. For them, the break describes the condition of the marginalised, or what they conceptualise as the undercommons. They are always in the break, always the supplement or addition, never the whole. For them, study is “what you do with other people”. Study for them is a refusal to bleed out and heal, and an insistence on the undercommons – that which continues to be both refused and refuses. It is a practice not of seeking to be recognised within existing forms of value, but to disrupt and exist despite them. Their work comes from blackness studies and a critique of capitalism, so their idea of the undercommons, and study as the activity that happens within it, is a rallying cry against the professionalisation of the university, the individualisation or atomisation of society and the cutting, or binaries, that separate disciplines or people into categories. This is a call to remain indeterminate, to remain in a different kind of flux than a presumed porosity: to insist on the break, the opaque.

The slash in in/vesting then seeks to function both to uphold the pertinence of pausing and to maintain the indeterminacy of singular definition or capture-able collectivity. The future-oriented applicability might lie here: in how in/vesting, with its roots and slippage – indeed, perhaps its porosity – to capital, needs to move from that current reality rather than seek to elide it. If → direct action (per Tjaša Pureber’s definition of the term)[13] can create pockets of temporal resistance in which alliances can emerge, thinking through in/vesting can create temporal pauses in which relations of power can be acknowledged, in order to then begin to move towards collaboration across and in sustenance of difference.

Towards a temporary use

The constituent museum, alongside its constituencies, might then begin to think of itself as an occasionally porous site. In/vesting as a weak line of flight would ask, as programming evolves and input is sought, as groups are invited in and left out, how mutually permeable these moments of encounter are, how long they might last and what the limits of our desired intimacies with each other are. Shifting between structural realities, historic power, epistemic dominances and individual relations, we might pause on the skin of the interaction. In/vesting becomes a consideration that comes prior to, during and after activities, a means of tracing the lines of power, intent and impermeability that underwrite an interaction that seeks to co-constitute.