In order to discuss the commons today, especially in relation to art and culture and speaking from our particular location, we must return at least 60 years back, to the 1950s, a period when Yugoslavia broke with the Soviet Union after it refused to submit to the latter’s domination, which left it in cultural, economic and political isolation from the rest of the socialist bloc. That also meant that Agitprop department, which until then controlled basically all cultural happenings in Yugoslavia (Agitprop took after the Soviet model and was controlled by the Yugoslav Communist Party) was abolished. Subsequently all these changes lead to the development of a new kind of state cultural politics – one based on self-management.

However, deliberations on the socialist cultural politics might sound anachronistic or even conservative, especially if observed in the light of current museological discourses on the so-called new prototypes of art institutions, uses of art, educational turn, participation in art and so on. In addition to all these categories the very notion of “working class” which represented the most important part of the self-management system has also become obsolete, especially due to the fact that in most of the Western world immaterial → labour has to a large extent replaced industrial work. Compared to the now historical proletariat → the contemporary cognitariat does not constitute a class. Seen in this light the socialist self-managed museums, their governance and the content which such museums provided could be considered today as conservative, subordinated to the state, ideologically restricted, highly → bureaucratised, while favouring conventional art formats, didactic means of providing knowledge about art and so on.

But, on another level, can we still even consider the question of class struggle and class struggle related antagonisms within art institutions nowadays, as used to be the case in Yugoslavia? What about the dichotomy between elitism, intellectual elitism included, and social and political engagement in such institutions? Or to put it in terms of a more modern vocabulary: How does the process of communing – a social process that creates and reproduces the common – happens within the cultural field today?

In order to answer some of these questions I would attempt to link some progressive socialist cultural policies, museum models and directions, as well as their → emancipatory utopias, to today’s deliberations on the new prototypes of art institution – “a museum of the commons”. It is not a coincidence that in many socialist countries around the world art and politics were united in their quest for creating utopian models adapted to social and political changes, especially in the 60s and 70s. Experimental museology and concepts such as the integrated museum, social museum, living museum, and museum of the workers were widely discussed in the so called → Global South. Progressive cultural politics considered culture and art as “commons”, something that belonged to all; at least that was the case in theory.

Figure 1: J. Depolo, “Slika, kip i prostor”, Vjestnik, 23 October 1960.

Now let’s return to Yugoslavia. As a consequence of all the political events and specific economic climate in Yugoslavia in the early 50s, self-management was introduced, even though some have identified the origins of Yugoslav self-management already in the Second World War anti-fascist committees. Its main ideologue was Edvard Kardelj[1], and it was promoted by economists like Branko Horvat, theoreticians like Darko Suvin, Rudi Supek and others. They not only affirmed it, but were also critical towards it. Self-management had a profound influence on the society as a whole: it introduced a new type of managing labour organisations, the working people’s participation in decision-making, and workers’ councils. Self-management brought about increased → autonomy of production economic units, which was a step forward from the planned economy as practiced in the Soviet Union, as it handed the factories to the workers, moving towards the withering of the state. Workers officially managed the “socially” owned means of production (associative labour). Self-management was also introduced in cultural institutions, where it was called “social management”; with the museum workers’ council, and later on with the delegate system, a collective body with a third of its members who were representatives of the employees and two thirds were external members who represented “social interest” in the activities of the institution. The basic idea was that those producing and those consuming culture jointly decided on matters of importance for the institution, i.e. the financial plan, annual accounts, the work programme. Stane Dolanc, a high-ranking Yugoslav Communist Party official, said in his speech in Moderna galerija, Ljubljana in 1973: “The new position of culture in socialist self-management destroys the historic wall between the working masses and the culture.”[2] This new vision also produced a change in the interpretation of culture: culture was not anymore considered as artistic expression per se, but included all types of creative manifestation – in physical labour, politics, social life, education, science, and new solutions in social services. Culture was less and less treated as a sector and more and more as an integral part of the overall creative effort of society, a link providing interaction between intellectual and physical labour.[3] The old “statist culture” was replaced with the so-called “socialised culture”. (Figure 1)

In a specific way it was the 1950s which were a period of cultural blossoming in the former Yugoslavia. For example: the formal status of a freelance cultural worker was introduced (including all the social benefits), a significant part of the national budget went towards numerous cultural activities, modernism was introduced as the favoured style (modernist works were thus sent to biennials), and cultural infrastructure, including museums, was built or reconstructed. Some of the main concerns of Yugoslav cultural policy at that time were, for example, including culture in the entire socio-economic context and transforming citizens from passive users into active co-creators of culture; which is definitely something that could also be observed today in the context of the “commons”, as I already mentioned. The goal was that art (also top-level or high art) and culture were to be accessible to all. The idea behind this was to teach citizens/workers how to manage their country better. Such as, for example, organising the didactic exhibitions, which was already happening in 1952 in Moderna galerija[4], or perhaps the better known Didactic Exhibition on Abstract Art[5], an educational attempt by a group of artists from Zagreb in 1957. The exhibition was highly successful; it travelled all around Yugoslavia for almost ten years and was set up in various spaces: city halls, schools, and museums. Booklets on art were also produced within workers universities, and so on.

Figure 2: Ivan Šučur, “Kugla kao simbol [Sphere as a Symbol]”, Borba, 7 July 1974, no. 183, year III. On three new sculptural works in public spaces in Maribor. On the photo: Janez Boljka, Atomic Age.

As noted above, these cultural practices took many different forms, including for example amateur cinema and photo clubs, which were established in factories and other workers’ organisations. They provided opportunities for avant-garde experimenting in the spirit of socialist self-management. This is really a special case, similar to that of the Soviet Proletkult from 1917, because in this way certain links were maintained between the so-called high culture and the workers. If workers didn’t come to the museums and galleries, artists and museum workers would go to the factories. In museums of modern and contemporary art in Yugoslavia, especially after the 1970s, art was brought from the museums to factories, to workers’ associations and so on, where special seminars on modern art were conducted with the goal of reaching the broadest possible public. One such widely recognised program was called “forma viva”, a sort of artists in residence program, where artists were temporarily working in various factories, and in exchange for the materials used they would in return leave their works to the factory. (Figure 2) Some of them, (for instance, the Panonija Agricultural Complex in Vojvodina) even built their own cultural centres with studios for painters. Others, such as the Podravka food producer[6] in Croatia or Lek pharmaceutical producer in Ljubljana, opened art galleries; the steel works in Sisak, Croatia, or steel factory Ravne na Koroškem in Slovenia also established → collaborations of artists with workers for jointly creating art works. The idea was to transform all forms of human labour into a creative activity, and this particular direction was known as the “culture of work”[7].

But what is also interesting is that at that time we had two different understandings of the idea of the “commons” in culture. The first was the official one, linking self-management with culture, opening the museums to the working people, educating all levels of population, etc. This direction included workers as an important part of the process of commoning, where an emphasis was put on the so-called “socialisation of culture”. The → slogan was: Culture to the people!

Figure 115: J. Škunca, “Vizija svemirskog reda” (“The Vision of Cosmic Order”), Vjestnik, 26 Octobe 1968.

And the other understanding of the “commons” was the alternative or more utopic one, the one which included, for example, the 1960s neo-avant-garde collectives where art was to become life, belonging to everyone in a process of democratisation of artistic production and reception, or the alternatives of the 1980s which were very much connected to the wider social and political movements of that time in Yugoslavia. Actually, many art collectives were organised on something that from today’s perspective could be seen as the principles of self-management. In the sense of Massimo de Angelis who said: whatever is produced in the common must stay in the common. So, paradoxically, since there was no art market for those works of art, art was in a way emancipated from the “aesthetic regime”, and the artists able to create without the interfering interests of the state or art market, so art could stay in the common. (Figure 3)

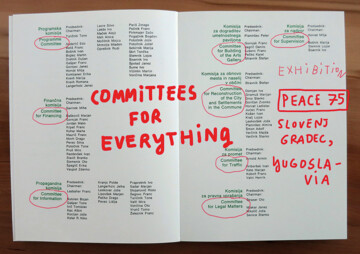

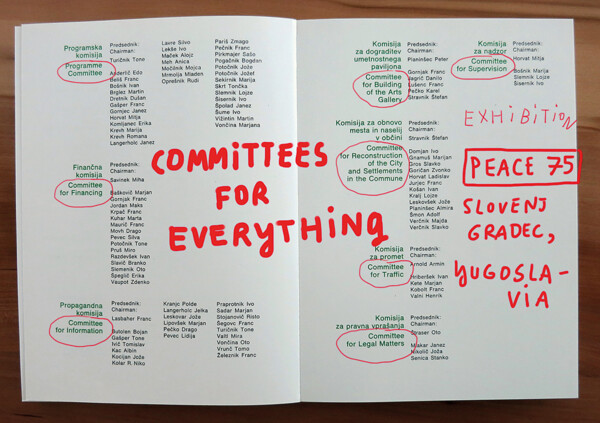

Figure 4: From the exhibition catalogue Peace 75 – 30 OZN, Art Gallery Slovenj Gradec, Jugoslavia, 19 Ictober 1975 – 19 January 1976.

The negative side of self-management was a high level of → bureaucratisation; it was a very complicated system, with committees, assemblies, interest communities, chambers of working people and the like, established for basically everything, demanding too much time from workers who had to engage in various tasks for which they were not competent. (Figure 4) Moreover, conflicts between artistic missions and the collective management of the institutions were inevitable. It has been said that the introduction of self-management in culture only meant “to break cultural nationalism down into harmless units and to reduce the danger of elitism and cultural centralism”.[8] There were also huge gaps with regard to the uneven economic and cultural development in various parts of Yugoslavia (a north-south division). As a consequence, the so-called “demetropolisation of culture” happened in the 1970s, with houses of culture being built in rural areas all over the country, stimulating and favouring amateur art production.

Opposition to the socialist system, even in the form of irony, was often sanctioned; for example, many Black Wave films were banned, film directors not allowed to film, writers were occasionally accused of being “bourgeoisie” or enemies of socialism, could not publish their works anymore and so on. However, many artists actually commented that it was basically possible to do almost any kind of artistic experiment during the time of socialism, with two exceptions: criticising President Tito and the Yugoslav Army. A quite well-known case is the Oktobar 75[9] project from Student Cultural Centre (SKC) Belgrade, where a group of artists organised a symposium on art and political engagement. Dunja Blažević, who was a head of the SKC visual program at the time, proposed that various artists to critically rethink “the sphere of socialist self-management in the sphere of culture”. However, the one kind of criticism that was not tolerated was criticism of the left which came from the left itself.[10]

At the end this model – self-management – failed to be part of the actual “workers struggle”. There are many reasons why it failed, although these are far too complex to debate in the frame of this text.[11]

There are some important points to be learned from the Yugoslav self-management project, not only to resurrect some forgotten traditions and cultural practices, but also as an alternative to the prevailing Western cultural model. Looking back at what happened in the 1990s, it is quite obvious that museums in the former socialist countries of Eastern Europe integrated into the global art system, adapting to a greater or lesser degree the Western canon of art history and subsequently to the logic of capitalism. What we are interested in today is not the repetition of old ideas, but rather considering self-management as a counter model to think about new forms of commons, also in art and culture[12].

Credits: I would like to thank my colleagues from the Archives Department of the Moderna galerija for helping me with the archival materials.

![Slika, kip i prostor [Painting, Sculpture and Space]](/website/var/tmp/image-thumbnails/0/1243/thumb__logo/F113-2i_1960.jpeg)

![“Kugla kao simbol [Sphere as a Symbol]”](/website/var/tmp/image-thumbnails/0/1246/thumb__logo/F114_4f_1970.jpeg)