Kapwa[1] is an indigenous Filipino (Tagalog) term of psychology whose root is anchored in pre-hispanic, pre-colonial thinking, a cultural ethnic attitude of “the self in the other”. This is a relational attitude between generations, where each individual acknowledges their relevance and responsibility to carry forward their ancestral collective significance, and in particular with respect to their local community and natural environment. The “self” is an integral part of the “other”, and thus intertwined, an action outside of the self is innately an action within. Such an attitude can be found in the diaspora of Asian psychologies, most coherently expressed by the renowned Vietnamese Buddhist Thich Nhat Hanh:

"There is the collective consciousness and the individual consciousness. Our individual consciousness is made of our collective consciousness, and our collective consciousness is made of our individual consciousness. We reflect everything. And everything reflects us. And the process begins with yourself."

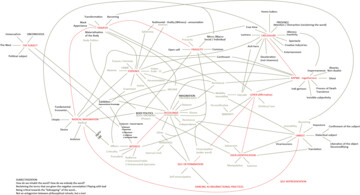

In short, the kapwa of an individual can be likened to a kind of ethical spirit of relational subjectivity (within Confucian thinking the concept is referred to as ren), whereby the actions of one can be said to represent the actions of a collective and, in turn, to speak with respect to the order of the universe. Unlike concepts of “The Other” that place the self as something that it is not, the relational concept of kapwa understands that everything within and beyond is an extension of the self, and ultimately representational of a harmonious community.

Such non-Western or indigenous forms of discourse on human subjectivities have been significantly eroded under the colonial project, whereby foreign economic and linguistic systems were imposed on communities, thus inherently altering their relational concept of human → sustainability. As Professor Paredes-Canilao points out:

… we find in Chinese and Filipino cultures discourses that are more ontologically, epistemologically and culturally empowering for the → decolonisation and cultural politics of colonised subjects. These discourses express and construct a notion of self-identity that is integrally connected to others and to the bigger cosmos. This is the moral force binding intercultural community that is found wanting in the postmodern desire for difference.[2]

Such moral force, a particular respect for or belief in the need for balance and harmony among thought, action and impact on the animate and inanimate worlds, is also a model discussed by Professor Prasenjit Duara in his book The Crisis of Global Modernity: Asian traditions and a → sustainable future, where he calls for a new ethic of human → agency, highly critical of the neoliberal individual in its creation of nation states for their erosion of respect between man and our interconnectedness with the physical, spiritual and cosmological worlds.

While choosing to unpack the relevance of kapwa as a basis for re-thinking the aesthetic and artistic traditions of subjectivisation, this is also a useful prism to challenge the concept of artistic → labour within a certain practice, and particularly for challenging ideas of individual socio-political responsibility in artistic communities. I am struck by how many artists across the postcolonial world are responsible for initiating spaces/ → archives of cultural public relevance and, in turn, directing, sustaining and ultimately informing their communities about the necessity of a historical consciousness that embraces the idea of kapwa at its core (here I think particularly of the Long March Project in China; Lugar a dudas in Colombia; Centre for Historical Reenactments in South Africa; Bophana in Cambodia to name but a few).

Kidlat Tahimik, Bakit Dilaw Ang Kulay ng Bahaghari (Why is yellow at the middle of the rainbow?), film/colour, 175´, Philippines, 1984/1994. Courtesy of the artist.

Kidlat Tahimik, Memories of Overdevelopment, film/DVD, OV (English), 33´, Philippines, 1984. Courtesy of the artist.

While kapwa may be linguistically located in the Filipino cultural psychology, its ethos can be located in a number of differing transnational artistic practices, with differing terms, across the field of contemporary art, particularly in Asia. Recalling aesthetic traditions intimately linked to spiritual values, artists refer to the interconnectedness of the animate and inanimate, perhaps framed between what is institutionalised and what is intuitively experienced – be it through the documentary retelling of religious discrimination in South Korea through shamanistic texts (Park Chan-Kyong, South Korea); the wilful investment of “belief” in informal collectivised faith in the healing that occurs within supernatural traditions (Truong Cong Tung, Vietnam); most tellingly, kapwa is encompassed in the filmic works of the Filipino artist Kidlat Tahimik, a member of the Third Cinema Movement. His life’s work is committed to an awareness of how his moving image novellas, that span a 35-year period of production, present his “self” anchored in the local traditions of time, while simultaneously enduring colonial and capitalist dictations of class and representations of self-hood (i.e. in economic terms). His filmic collages in essay form stunningly illustrate the resistance to, and embracement of, the flow of the dollar as a symbol of progress but at a great sacrifice of one’s kapwa (see Why is yellow at the middle of the rainbow? and Memories of Overdevelopment, in particular).