One of the crucial movements in the art of the 20th century is the one away from making decisions about “quality” based on an idea of subjectivity detached from an assessment of how the individual relates to society. This relates to two contradictory insights.

The first one is Hannah Arendt’s insistence, in The Life of the Mind, that judgment cannot be reduced to the criteria we might establish for it before the fact. We should not try to justify quality as another form of quantity. Any real notion of quality is based on a radically unpredictable act of judgment that manifests free will. Subjectivity is, therefore, ethical.

The second one is Marcel Duchamp’s revelation of his “readymade” a hundred years ago, which transposed the quest for quality into an analysis of function. He appeared to celebrate chance and move away from the established form of subjectivity that we might term “being an artist” – but secretly he remained a very talented genius.

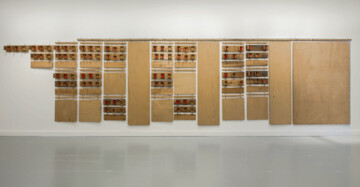

Figure 1: Robert Filliou, Principe d’ equivalence (Principle of Equivalence), mixed media, 200 x 1000 cm, materials: wood, iron, felted wool, 1968. Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris. Photo: © M HKA.

Duchamp’s stance was further radicalised by Robert Filliou – the self-professed “genius without talent” – when he formulated his Principe d’ equivalence (Principle of Equivalence) fifty years ago. (Figure 1) “Whether a work of art is well made, badly made or not made at all seems indifferent to me, from the point of view of permanent creation.” This puts the ethics and aesthetics of subjectivity into question.

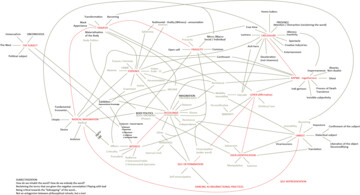

But back to our chosen term!... In 1993, the organisers of Antwerp’s year as European Cultural Capital published the book About the Interesting: Discourse and Literature, with contributions by Umberto Eco, Jean-François Lyotard and others. Twenty years ago, under the indirect influence of Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network Theory, a new generation of artists began to question the ethics and politics of subjectivity. From “Relational Aesthetics” in the mid-1990s until “Post-Internet Art” today, subjectivity remains the least understood factor in the smooth functioning of the → Network, whether it is seen as a web of human social relations or a technological → noosphère.

Yet in 2014, it is still impossible to programme a museum of contemporary art without taking an informed and critical position on subjectivity. Two words are almost impossible to let go of: “important” and “interesting”. They sound vague and self-righteous while in fact they attempt to look beyond the understanding of subjectivity as something purely individual. Both words try to introduce an element of social comparison into the notion of quality. More interesting than what? More important than whom? And why?

Figure 2: Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven, Nursing Activities, Firect (Pulverizing) (detail), 1995–1998. Collection M HKA, Antwerp / Collection Flemish Community, © M HKA.

Importance is somehow less subjective than interest. But even interest is a social notion – and not just in the sense of the money we pay to be able to borrow money. The Latin expression inter-esse is translated as “to be between, make a difference, concern”. These definitions all imply that interest is to do with a certain plurality; it would be much harder to be “between yourself” than to be between yourself and someone else, and difference always concerns a comparison between at least two things (or two aspects of one thing). (Figure 2)

Nevertheless, interest remains a good approximation of what “enlightened” or “progressive” subjectivity might be today. And in the life of an institution, it is a rather useful state of mind. Interest is grounded in an emotional conviction on the one hand and rational analysis on the other. It is slower and more thoughtful than, for instance, “enthusiasm” or “urgency”. Therefore, it is more → sustainable and less prone to political and managerial mood-swings.

Enlightened, progressive professionals – and members of what is called the “interested public” – should bear in mind the two etymologies of interest: the inter that connects us to other subjects and the esse that reminds us that we should have some idea about existence. And of course, interests also remind us to be critical of that other unresolved topic of Western civilisation: Immanuel Kant’s notion of “disinterested” spectatorship…