How to share the void? On the concept of basic income.

I could speak about the recent five years, which I experienced as an activist, but when we compare all that has happened with the current situation of new media, public speech and the related problems – how they are distributed and influenced/distorted, the responsibility is very big, and somehow we think twice about how to speak and what to say. Most of the people who spoke a lot at the beginning and demanded positive social change, we never gave up the idea and we still believe in it; and we never forget the sacrifice of those, who sacrificed their private lives or even their lives. But the mechanism of the distribution of free public speech has changed a lot. Exactly because of the mechanism of distribution of reality behind new media, we still demand the freedom of all the prisoners of conscience, but the question is: How can we address those who keep them detained? What are the tools and media distribution for this to avoid mistakes?

Three years ago I decided to work on ecological design and not as a political human rights activist, who attacks power. Instead of demanding systemic change I planned to set common, positive goals for conflicting parties. No more fighting – just creating something positive. Something that offers hope and gives us mental strength.

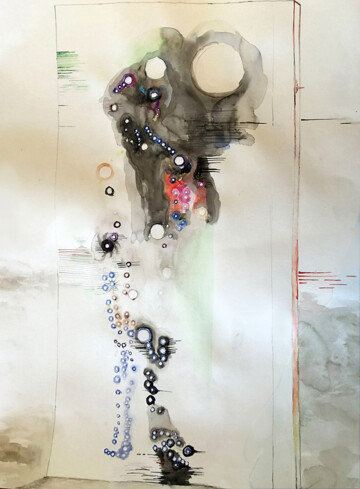

Figure 1: Róza El-Hassan, The Gate: With the Letter Syn, S, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

I am working in the field of earth-architecture and currently present my work on an exhibition in Museen Basel (28 May – 3 July 2016), entitled “Future’s Dialect”. It is a → collaborative show with Martha Rosler, who presents the counter-theses to my silent work criticising the system in a very brave and subversive way. The show is also about another topic, of which I would rather not speak extensively, because I do not want to promote just my art here, but would rather try to add something to the discourse. It refers to a topic where I do not endanger others, do not repeat false information, and where I do not have to lie. This seems still a very valuable thought for me. (Figure 1)

Instead of this topic, I have chosen the notion of basic income and art, which can be a very interesting aspect concerning the Commons, the subject of our talk. This was influenced very much by Tamás St. Auby, one of my professors at the Academy of Fine Arts in Hungary in the early nineties. He introduced us to his theory of IPUT (International Parallel Union for Telecommunications) and the notions of a basic income, subsistence level and many Fluxus-related art theories. One of the ideas was that artists must not work (or to be exact, that art cannot be described with the notions of → labour or work or production) – he was also very much in support of and often practicing a general art-strike.

In the early nineties, I studied art in the newly founded Intermedia Department in Hungary. There Tamás St. Auby spoke about his utopian theories on the border of traditional spirituality, art, and social change. One of the notions, which returned in his lectures, again and again, was the that of “basic income”. We heard from St. Auby about monks in Tibet who never worked and the community always provided support at a subsistence level, we heard about the new and eternal role of artists after the Fluxus movement: Artists should never be forced to work, and the community should provide a minimal income for them to survive. Artists and monks serve the community. Work in the 1970s during state socialism in Hungary was often disconnected from creativity – but also even from real production, since there was no free market. Humans were a kind of robots and St. Auby was punished with exile for his rebellious ideas.

On the other hand, Beuys said “everybody is an artist” If we summarise the two manifestos (of St. Auby and Beuys) we ask: “Should all the people have a basic income?” Twenty years ago all this sounded to me like an artists’ subjective mythology on the level of social and metaphysical utopia or subjective politics. Suddenly, in 2016, I bumped again into the notion of basic income. This time, it is a real economic proposal to provide for all people a basic minimal income, and an idea that is now broadly discussed in the media. One of the ideas in the background is to ease the tension of people who try to find jobs in vain and the social tension in general in times when there are fewer and fewer jobs. Too much social tension arises because of the competitive fight in society for work and employment. Robots will also take over some of our work.

Meanwhile, most of agriculture is automated, so most of the rural work is gone and countries have become deserts because of climate change, other countries have very high wages and it has become nearly impossible to produce (e.g. in Switzerland) simple goods in the global competition for low production prices. The tendency is to disconnect work and income, to disconnect the redistribution of goods from work and by this from Marxist theory, which is based on the notion of a working class. The economic concept of basic income and the first experiments in poor countries are on their way, for example in India, and the discussions takes also place in welfare states like Switzerland. Of course, the basic income in India is ten times smaller than in welfare states, but the principle is similar.

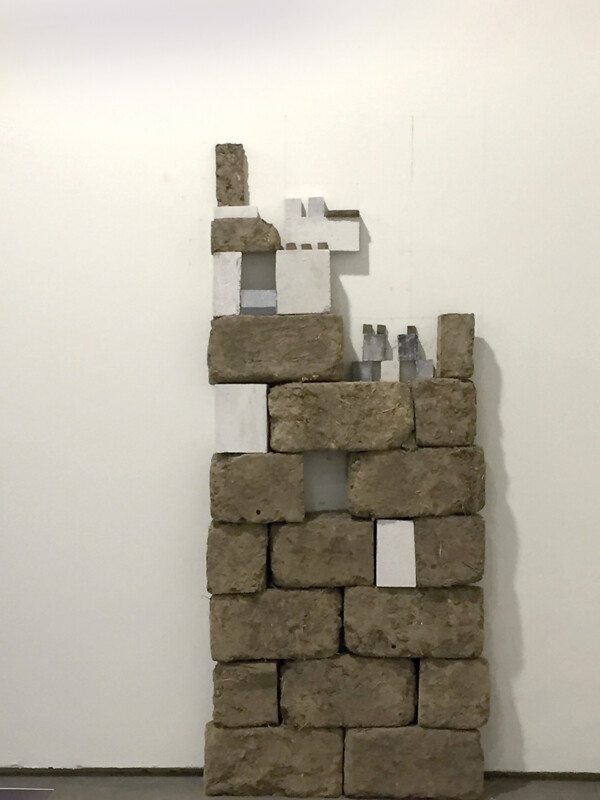

Figure 2: Róza El-Hassan, Backlight, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Beyond the economic aspect, I am remembering lectures of Tamás St. Auby, which showed us that a basic income was traditionally the privilege of monks and spiritual communities or groups. A life without work was connected to a high degree of spirituality or to art. The Buddhist monks spent a lot of time on fasting and meditation. Andrej Rubljov was painting, the hippies and Fluxus people of the seventies smoked grass and were fasting, too. The question arises, how will a society psychologically and mentally regulate itself in times when machines take over most of the work and humans will receive a basic income? (Figure 2)

How will we share the void?

What will the lack of work bring, what creative work and what tools of production? How will we share the spirit? What will be the role of art? What was and will be the role of collective fasting as practiced in traditional societies, and religions (e.g. during Ramadan in Islam) or suggested in modern advertisements’ stereotypes and by vegan life-style and dietary movements – although it was predicted to be nearly lost as a respected discipline in Kafka’s “The Hunger Artist”? What will be the role of sports and yoga, will they be able to fill the hole of having no work?

At the end of the nineties – going hand in hand with the postmodernity of the third industrial revolution of the internet – we spoke of the creative industries – art and creativity as a tool to increase marketing and development – as described in exhibitions and texts – one of which impressed me very much, and this was “Be creative” by Marion von Osten.

Today, five years after the sudden revival of new revolutionary movements, as happened with Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring, followed in many places by a deep humanitarian crisis and horror, we have to think about the new roles of art. It is no longer a neo-liberal creative industry anymore, but art in times of crisis, ruptures, sectarian fights, and war. It is a question how to share the void. I think art is very important and can save society.

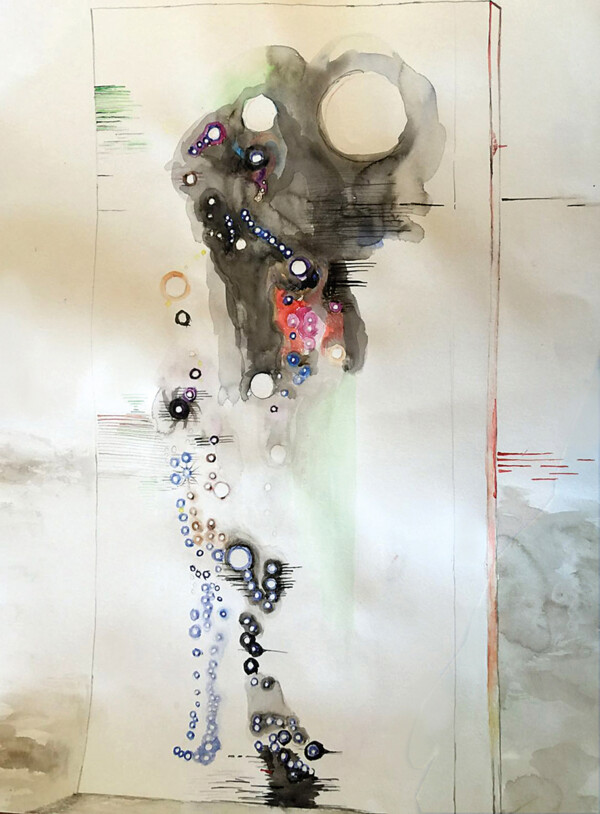

Figure 3: Róza El-Hassan, Fours: Breeze 7, Future's Dialect in Antwerp, 2015 (Adobe Dome and Stars painted on the floor). Courtesy of the artist.

In my artistic works, drawings, objects and buildings, such as the Breeze earth domes or wicker laptop bags, I design often small, new solutions for an economy, ecology, and life practice. (Figure 3) In my personal artistic practice, ecological design is connected with spirituality. While describing my notion of “spiritual design” I am aware that I use a prohibited word in contemporary art. Still, we have to share and redesign the void.