Notes on bafflement: The universal right to baffle

The term I present is not a part of the usual common(s) vocabulary; it does not stand for a function or a feature, but for an act, and for a certain effect: I would like to speak about the gestures that are baffling, and about the state of bafflement. To baffle is a certain (common) right of the disprivileged, powerless and deprived in the situation of confronting the violence of power.

Bafflement is not a trick nor a tactic used in the process of negotiation; it is an act that comes after the possibility of negotiation proved impossible. In a time sequence analysis of a conflict, bafflement occurs either when one side seems to be already defeated, or when the sides in the unfolding conflict are dramatically → asymmetric with regard to their power.

To baffle is not a part of the “tragedy” or of “comedy” of the commons; it is neither a resource nor a strategy. It is one right no one can undo or deny; to make the attempt to turn the existing set of circumstances upside down, to try to unilaterally change the existing paradigm itself.

To baffle is a political and material gesture (has consequences; exists in the form of act). But the history of bafflement outlines no clear “theory of baffling”, as no two bafflements are the same. There is practice of bafflement, though. Successful instances of (political) bafflement are rare, by the very nature of its use, and most of the unsuccessful attempts we will probably never know of.

It is and should be a common thing, even a right under certain circumstances, to baffle; however, no act of bafflement is or could be common. Political bafflement is always a singular act.

The notion of political baffling emerged as one of the outcomes of the research project and the publication titled On Neutrality I recently did together with Rachel O’Reilly and Vladimir Jerić Vlidi, examining the concepts of “political peace” and “active neutrality” in the gestures of the → Non-Aligned Movement. The politics of active neutrality was opposing both the Euro-Atlantic juridical management of political neutralism and the Western ideology of peace.[1] At the same time, it was introducing something new and unexpected – “uncommon” – that can be summarised in Edvard Kardelj’s thesis of the Non-Aligned “third position” in his Historical Roots of Non-Alignment. This thesis, a certain twofold negation of the power-blocs, does not imply reaching the point of ideal “equidistance” from the existing centres of power, but (actively) countering the power politics as such.

What follows is a few historical examples of situations when for the disprivileged to baffle was the only option left. In some cases, it worked, at least temporarily, for the situation to change in favour of their cause; in all of the cases it succeeded in producing the statement of truth and of justice; in invoking the paradigm of the future. In those moments, at least briefly, the power had to stop advancing, experiencing what those submitted to it live as a daily experience: disorientation, disbelief, and the sense of loss of any logic or legitimacy in what they thought is a “valid” social contract of the moment.

Our common protection is the privilege of being allowed, when in danger, to invoke what is fair and right

An early example of such countering the power politics can be found in the historical-literary writings of Thucydides, the Athenian strategos (general) and one of the earliest Western historians. In the war between the state of Athens and Sparta in 416–15 BC, as his chronicles of the Peloponnesian War state, the Athenian army came to confront the island peoples of Melos. The population of the small and militarily much weaker island was considered to be historically closer to Sparta but now independent and, until the Athenians showed up in full force, explicitly not wanting to take part in the war. The Athenians then posed to the Melians one simple and unambivalent demand – to submit or be annihilated. However, they did accept to have one final meeting the representatives of Melos asked for, presenting their consent to “negotiate” as the humanitarian act of an empire that takes care of the “safety” of its military operations, cunningly talking about their wish to preserve the Melian country and to avoid lives lost on both sides – but only in the case that Melos unconditionally surrendered to their rule. What became known as “The Melian Dialogue” (the conclusion of our research proved that it was rather “The Athenian Monologue”, with certain important responses added), as written by Thucydides, went along these lines:[2]

Athenians: If you have met with us to reason about presentiments of the future, or for anything other than to consult for your safety, we will give over; otherwise we will go on.

Melians: It is natural and excusable, for men in our position, to turn more ways than one – both in thought and utterance. However, the question in this conference is, as you say, the safety of our country…

Athenians: We shall not trouble you with specious pretences, and make a long speech which would not be believed … in return we hope you don’t say that you have done us no wrong and know as well as we do that right’ is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.

Melians: YOU ask us to ignore what is right, and talk only of interest – [BUT] our common protection is the privilege of being allowed, when in danger, to invoke what is fair and right, and even to profit by arguments not strictly valid if they can be argued well.

Athenians: The end of our empire, if end it should, does not frighten us: we come here in the interest of our empire, and the preservation of your country.

Melians: How could it be as good for us to serve, as it is for you to rule?

Athenians. Because you would have the advantage of submitting before suffering the worst, and we should gain by not destroying you.

Melians: So you would not consent to our being neutral, friends instead of enemies, but allies of neither side?

Athenians: No; for your hostility cannot so much hurt us as your friendship will be an argument to our subjects of our weakness, and your enmity of our power.

Melians: Is that your idea of equity, to put those who have nothing to do with you in the same category with peoples that are most of them your own colonists, and conquered rebels?

Athenians: As far as right goes … if any maintain their independence it is because they are strong…if we do not molest them it is because we are afraid; so besides extending our empire we should gain in security by your subjection; the fact that you are islanders and weaker than others renders it all the more important that you should not succeed in baffling the masters of the sea.

Melians: How can you avoid making enemies of all existing neutrals …. if you risk so much to retain your empire, and you risk your subjects to get rid of it, we are surely base and cowardly if we are still free and don’t try everything that can be tried? … to submit is to give ourselves over to despair ... action still preserves for us a hope that we may stand erect.

Athenians: Hope, danger’s comforter, may be indulged in by those who have abundant resources…

Melians: ...we are as aware as you are, of the difficulty of contending against your power and fortune. But we trust that the gods may grant us fortune as good as yours, since we are JUST men fighting against UNJUST… Our confidence, therefore, is not so utterly irrational.

What caught our attention in this exchange between the Melians and Athenians is precisely the political logic of the supposedly non-pragmatist and “irrational” Melian response to the historical expectation of their submission, and the Athenians’ persistence with a purely economical and cynical interpretation of the Melians’ positioning.[3]

Borrowing from the Athenians’ own wording, in the essay-book On Neutrality we called this Melian manoeuvre and the Athenians’ response “bafflement”, which is precisely what happens in the reception of the stated non-aligned position of those not attributed with power. It historically repeats in the reactions of large powers – over and over again – regardless of how rationally, patiently or logically the position of (non-)alignment is argued.

Power politics excludes the powerless, placing them below the threshold of waging any consequential politics, beyond the possibility of participation in world affairs as serious political partners – it denies their capacity to think and act towards the production of commonality, it neglects them as political subjects, it infantilises their attempts to self-position and → self-determinate. The gesture of political baffling is a performative way to state “we are small but we have politics”. And such a statement is often connected with the most dramatic situations, structured around the issues of war and peace, life and death, survival or annihilation.

The act of political baffling always includes risk, but the kind of risk that is not a calculation within the parameters of the known that could be potentially beneficial or profitable. Importantly, to baffle is not to bluff! It is rather a total risk, which is often the only – and the common – ticket the disprivileged have to participate in politics. This risk is usually contained in the possibility of invoking the new paradigm too soon.

The risk of invoking the new paradigm too soon. Against the rationality of positions of those who participate in power politics (NAM conference – Belgrade, the demands)

The inaugural Conference of the Non-Aligned countries held in Belgrade in 1961 was constitutive for this international movement, struggling for → decolonisation of the world, negating the rule of power politics and imposing the demand for a complete re-arrangement of the power relations in the world.

The Ambition of Belgrade, 1961:

...the general situation in the world, the establishment and strengthening of the international peace and security, respect of the right of nations to → self-determination, the struggle against imperialism and liquidation of colonialism and neo-colonialism, respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the states and non-interference in their internal affairs, racial discrimination and the policy of apartheid, general and complete disarmament, the banning of nuclear experiments and the maintenance of military bases on foreign territory, peaceful coexistence among states with different social systems, the role and structure of the United Nations and the application of its resolutions, an equal economic development, the improvement of international economic and technical cooperation, and a number of other questions.[4]

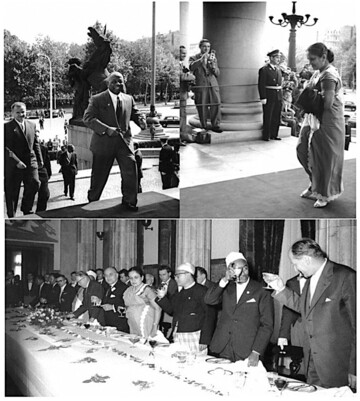

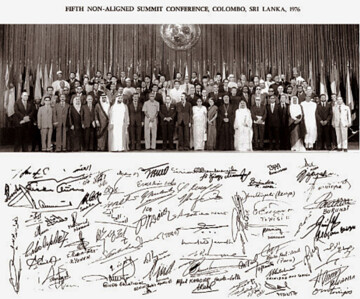

Figure 1: Photo documents from the first Conference of Heads of State or Government of Non-Aligned Countries, September 1961, Belgrade. Courtesy of Museum of Yugoslav History, Belgrade.

The very first NAM conference amazed the world by expressing the universal demand on behalf of all who are not in a position of power to reject and to dismiss the logic of “strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must”. The Non-Aligned demands had baffled the Power Blocs for merely daring to imagine turning the world “upside down” as they could see it, and for demanding the change immediately and with no further questioning of the yet-to-be elaborated new principles of a New World (because, that would be rational from the hegemonous perspective of instrumental reasoning).[5] (Figure 1)

Although it is sometimes part of diplomatic processes, baffling belongs to the ultimately counter-diplomatic register of political behaviour. Bafflement in itself coexists with the tactic of abandoning the rules of “proper” diplomatic conduct, which is set by power blocs. It is the last instance of a certain constellation/situation/relation; sometimes, it can be the first instance of the new one.

How could it be as good for us to serve, as it is for you to rule? (NAM conference – Colombo, the demands)

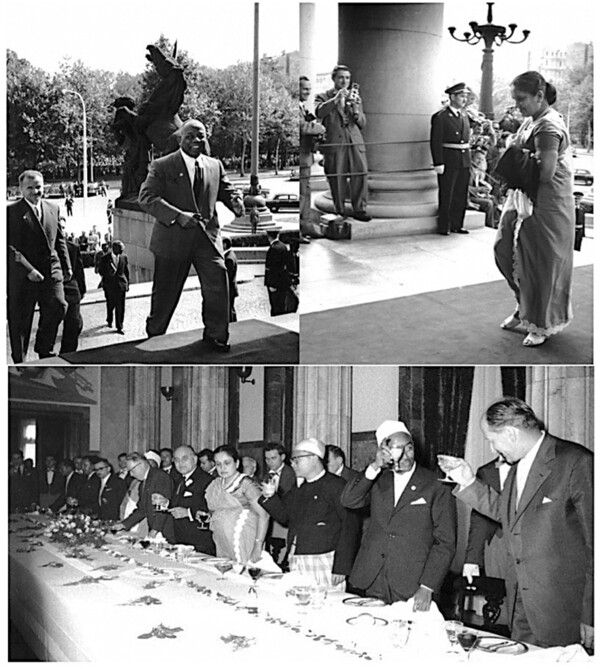

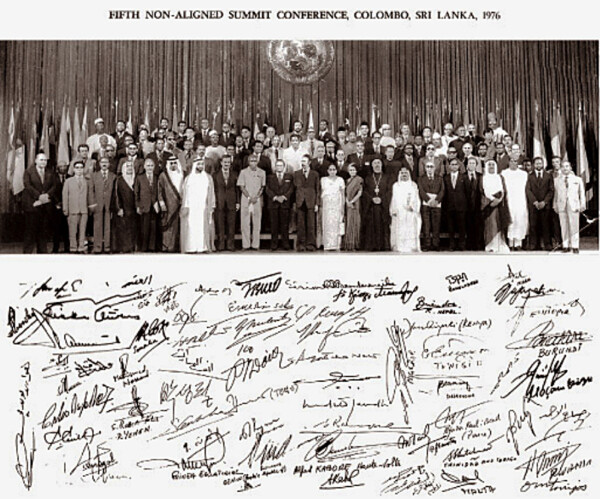

Figure 2: Fifth Non-aligned Summit Conference, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 1976. Courtesy of Museum of Yugoslav History, Belgrade. Courtesy of Museum of Yugoslav History, Belgrade.

The Colombo Conference in 1976, probably the biggest Summit of Non-Aligned countries, representing at the time “two thirds of the world” in numbers, again baffled the power blocs with its demands, now of an economic nature. (Figure 2) Met from the side of power politics by attempts to denounce or “infantilise” the Summit, the demands of those who rejected participation in power politics opposed (and baffled) the same financial oligarchy that up to the present day gains its power through the seemingly ever-rising rule of global capitalist corporatism. To the shock and disbelief of power, the NAM countries declared that the rules of global debt, as set by Western power players, might not be valid anymore, if those rules did not change to reflect not only “the economic reality” but also “what is fair and just” in any, including the financial and economical, mutual relations.[6]

The Demands of Colombo, 1976:

1. Immediate suspension of the foreign debt payment “of the poorest countries and those countries subjected to imperialist pressures”.

2. A “new universal monetary system”, which should replace the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.

3. The creation of new liquidity, which should be automatically coupled to the needs for worldwide development.

4. The world community of nations should be included in this “universal system” by means of triangular trade agreements among the developing sector, the socialist countries, and the developed countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).[7]

Power politics as a colonising force controls and distributes world resources, sets the canons/rules for political negotiation, implements the laws that keep justice on the side of power, and appropriates surplus value. It is entangled in and enwrapped by its own logic and absolutely confident about the operationally of this same logic. Therefore, the gestures inverting and fundamentally negating this very logic, whatever the price is or the consequences are, produce utter confusion and disorientation among the representatives of (the) power(ful). They cannot believe in what they hear and see, they are politically baffled, and this very moment of bafflement produces a temporary suspension of the logic of (the) power(ful).

Bolje grob, nego rob! Action still preserves for us a hope that we may stand erect

The act of baffling is not an abstract experience of a kind of a nominal political proclamation, but an actual, real experience, involving the bodily presence in a very concrete situation, and often some risk to life.

Figure 3: Demonstration of the people of Belgrade against the government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and its pact with Nazi Germany, 27 March 1941. Courtesy of Museum of Yugoslav History, Belgrade.

The demonstration of the people of Belgrade against the government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and its pact with Nazi Germany and fascist politics took place under the baffling political slogan “Bolje rat nego pakt, bolje grob nego rob!”[8]. (Figure 3) From this we see that baffling is often a negative statement, or is based on a term of negation, although it contains in itself a political proposition that, indeed, is a projective one – the proposition to envision the world differently.

To produce bafflement is often the only possibility for the deprivileged, powerless and deprived to “stand erect” in the situation of exposure to the violent aggression of power – to present their stand not as the retreat, not as the self-victimising call to humanitarianism, not as a particular mode of negotiation, but as truthful and strong defence of their own JUST (pro)position. To baffle is to act in defence of something that is, pragmatically speaking, indefensible, it is to stand for something what was not a part of the real-political options, nor customs, nor memories, before it was performed.

The political value of the gesture of baffling is precisely in its claim to what is non-existent, to what is impossible in the sphere of hegemonous rationality. Political bafflement leaves behind the entire morality and all the practical reasoning and dominant logic produced by whatever the existing power relations are at the time. The powerful are in most cases effectively shocked precisely by the “irrationality” that temporarily suspends the rational logic of power (what IS rational is the submission to the logic of power). The rationality in waging politics is almost exclusively reserved only for those who are in the position of power and who are supported by various laws, as they impose criteria and the very logic of such laws.[9]

Bafflement is the product of a non-calculating attitude, which is the main reason why the language of power politics categorises it as irrational or irresponsible behaviour. It risks everything – it does not have much to offer in the language of capital anyway. What it offers is the articulation and opening of all the ambivalences of a certain concrete situation, precisely by using the truth-speak that escapes the normative diplomatic and institutional forms of addressing and brings language to a different level, that is, redirects language to a different track of reasoning (thinking).

To baffle is never an act of aggression, although it can take a form that can be classified as violent. Violence as a possible reply to oppression is observed in political theory within the discussion on “just wars”. Important to note here, bafflement was never, as it cannot be, an act of terror.

Bafflement is an act of freedom precisely because it occurs in the situation in which one has “nothing/everything to lose”. To baffle is the last instance of the right one can call on in order to preserve freedom. To “die free” rather than to “live enslaved” is the ultimate message of the practice of baffling. The bafflement induced by such actions rests on the premise that freedom is more important than life, that is, that subjects deprived of freedom cannot accept such a condition as a valid form of human life, in however “bare” terms.

Therefore, the act of bafflement needs no authorisation, no contract, no agreement, no permission; it is not any traditional right, but is the right of (ultimate) need, and one that is self-decided upon; it should be considered a common right for anybody to decide if and when those in power are to be baffled. Bafflement always comes as unexpected, and frequently introduces its own formulation/argumentation for the very first time. Some historical acts of baffling preceded the very words of the principles they exercised, e.g. the cases of active neutrality, of socialism, of feminism, of anti-colonialism, of pretty much all of the semantic reflexions of equality. Perhaps it can even be said that for every emancipatory notion of principle, acts of bafflement had to precede these in practice before a certain principle was named and recognised.

The only resource required for the act of baffling is freedom, political freedom ... To baffle is to reject the ultimatum of power politics (“we will save your life, but you will be our slave”) which in contemporary times operates as the ultimatum of the choice of the politics of “lesser evil”. To produce baffling is therefore not a small gesture, nor a “modest proposal”. It is a big – and political – act of freedom, often able to make at least a tiny crack on the all-surrounding dome of dominant rationality, providing a glimpse into the possible better future and insisting that such a future is possible to materialise today, whatever the cost.