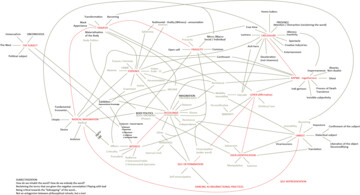

I understand subjectivisation to be the formation of a subject in relation to another. In this sense it is subjectivity in becoming, defined by what Felix Guattari saw as its “polyphonic” nature, open to and formed by many different inputs and influences whether they be psychological, cultural or political. Within this, and imbuing the notion of subjectivisation with a sense of political → agency, I propose the term self-determination.

Understanding self-determination as an ability to determine one’s own course can, in many respects, be seen as a product of Immanuel Kant and Enlightenment thinking. Opposing the proposition that we are unable to steer events in the face of higher forces such as nature and religion, thinkers such as Kant proposed that understanding our ability to “self-determine” thoughts, feelings and actions (thus linking self-determination to notions of free-will) was crucial in realising our capacity to shape → events in the world.

In the second half of the 20th century self-determination entered mainstream political discourse during the post-World War II settlement. It is tied to the establishment of the United Nations and a country’s right to choose its sovereignty or political orientation, free from external influence. By 1960, with the introduction of the UN Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and People, it became tied to the struggle of countries under colonial occupation, linking the discourse on self-determination specifically to the process of decolonisation. Indeed, it has underpinned colonial struggles and the rights of indigenous people, as countries or communities forge a new path for – and awareness of – themselves. Here the notion of self-determination constitutes what Benedict Anderson in the early 1980s defined as the prospect of Imagined Communities. Today, its resonance is most widely felt amongst those eager to banish the remnants of imperial rule and to understand how a collective identity, itself formed by a multitude of subjectivities freed from historical imposition, might articulate itself. It runs through the present political demands across the globe for new forms of political representation as new collective subjectivities form, and as they articulate their grievances and desires.

Within Europe, the continent from which I myself narrate and we as the Van Abbemuseum speak from, the question of self-determination (as a process of subjectivisation) is particularly pertinent as states attempt to free themselves from the bind of political unions (the United Kingdom, the Spanish Republic or the EU itself) from which they feel democratically excluded or that are driven purely by economic growth. Within this context, self-determination opens up a complex, often troubling field of debate, as it complicates accepted binaries of nationalism and internationalism, demanding that political subjects define their position and project their future beyond this simple bifurcation. It asks that we think again about the political formations of which we are a part and how we might re-imagine our role within them. In this sense, self-determination (as a process of subjectivisation) stands vehemently opposed to reactionary nationalism. Instead, it demands that we speak beyond established boundaries, whether they be the physical borders of nation states or ideological framings of left and right.

Within the current political conjuncture, wedded as it is to an outdated and dysfunctional neoliberal economics, the lure of self-determination for different types of political and ideological formations is potent. It means refusing the dominance of external forces, whether they are systems of governance or the market, and actively engaging authority and power. Yet the appeal of self-determination is that it goes beyond resistance to propose new social or political formations founded on emergent collective subjectivities, as yet unrealised or unforeseen. In this sense it appears to have affinities with Gramsci’s notion of the “organic intellectual”, who is tied to a collective political project, though often with no party to turn to. Here, culture is fundamental to any subjective process of self-determination, laying the ground upon which identities take shape and democratic processes can be formed. Culturally, self-determination thus opens up a vital space within an ever increasingly constrictive political and ideological sphere for how artists, practitioners and institutions define who they are, on what terms they operate and in relation to whom. Yet here we must insist on speaking of self-determination in relation to subjectivity: not for art to be self-determining, but artists; not museums, but those who engage with them. Self-determination, wherever it appears, must thrive off its subjective impulses.

Gerald Raunig has effectively identified the current ebbing away of the social democratic paradigm in Europe with the need to re-purpose institutions as the very sites where a new democratic process can be re-thought. He sees these as places of → resistance against the dominant order, defined either by the thrust of neoliberal economics or reactionary political forces. Breaking the false choice between these two positions is one way in which cultural institutions might play a leading role in what Raunig defines as “reinventing the state”. Raunig argues that cultural institutions are ideally placed to take on this role as they are able to foster an “odd mix of claims of → autonomy, frequently an experimental orientation, the self-evident expectation of critical stances and attention to political topics [that] enhances the potential for free spaces and turns art institutions into exceptional cases in comparison with other state institutions or those partly funded by the state.”[1]

With this in mind, the challenge for institutions would be to open themselves up to become institutions of → the common, meaning they make their resources, heritage and expertise available to all. More than this, however, it also entails institutions engaging in “a constantly present production of the common”, what Raunig sees as the “concatenation of singular currents, of the re-composition of multiplicity: the common as the self-organisation of self-cooperation”. This state of constant re-formulation and re-articulation holds resonance with Guattari’s understanding of the “polyphonic” nature of subjectivisation, contingent as it is on the ever-unfolding and pluralistic forces at play in any given conjuncture.

Here, the cultural and political potential of institutions is understood precisely through the framework of self-determination – both on the level of how they operate and how their perpetual process of becoming might play a leading role in new political formations. So, as museums redefine their public role as the state resets its relationship to museums and cultural organisations, the need for and potential of self-determination is both prescient and powerful.