Over the last hundred years, a long line of raised fists has punctuated history: from the tumultuous streets of the Weimar Republic to the defiant figure of the anarchist Federica Montseny at a political rally in the Spanish Second Republic; from the protests for sexual liberation in newly democratic Spain to the Zapatista liberation movement or Black Lives Matter; from John Heartfield’s photomontages to Picasso’s drafts for Guernica. These fists raised in unity, a greeting among those fighting on the same front, together form an “us” in opposition to a “them”. It is a transhistorical expression of anger and rage, and it encapsulates the → solidarity and comradeship among those who compose, with their bodies, a choreography of mutual aid in the public space. Some might say it is ideology-made flesh, embodied, because the raised fist is also an aesthetic practice of the subalterns. It is linked to leftist movements, but its openness, the fact that it is not strictly associated with any specific party or leader, has allowed it to travel through time. Furthermore, it has become an internationalist gesture, instigated by the → emancipatory struggles for social justice, equality and freedom.

The rise of the raised fist takes us on a journey of images through time and space, whereby we witness attempts to construct utopias of equality and fraternity, and we encounter new protesting bodies who use it to situate themselves in history. Gestures like this form a vocabulary that goes beyond the spoken word. From the perspective of → queer epistemologies, they are ephemeral, and, historically, they have therefore been erased from text, almost like the bodies themselves. “Concentrating on gestures atomises movement,” states José Esteban Muñoz, “these atomised and particular movements tell tales of historical becoming. Gestures transmit ephemeral knowledge of lost queer histories and possibilities within a phobic majoritarian public culture […] The gesture summons the resources of queer experience and collective identity that have been lost to us because of the demand for official evidence and facts.”[1]

From hand to fist

As a metonym for work, the hand is used in various different ways: it is the hand of the labour force, the body of the working class, the skill of the artisan, the might of the builder. During the 19th century, it became more and more prominent as a representation of the workforce, increasingly being depicted as their main tool and asset. In his introduction to The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man (1876), Friedrich Engels claims that work itself is a basic and fundamental condition of all human activity, and he even posits that man was created by work, part of an evolutionary process in which the hand played a key role. The most important step in the transition from monkey to man, i.e. the adoption of the upright position and consequently bipedalism, meant that the hands were freed up, and they thus began to take on other functions. Over time, the hands would be used in ever more sophisticated ways, in a process that also led to increased dexterity and a refined sense of touch: hands thus became very handy. This theory is somewhat similar to Darwin’s “correlation of growth”: Engels posits that the hand’s development correlates with that of other body parts and human functions. He suggests that these “new” hands triggered other changes that generally cannot be seen by the naked eye, such as adaptations in the digestive system or the brain (due to the creation of tools that would enable a new diet, which in turn had an impact on the relevant organs). Therefore, the hand is not only an organ for labour, but is also a product of it – the human being, in its most advanced iteration, exists because of work. Men and women are handmade.

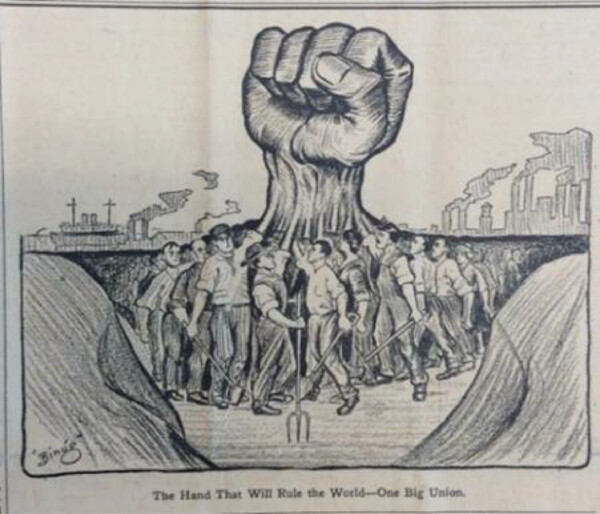

In Ralph Carlin’s illustration “The Hand That Will Rule the World”, published in Solidarity (the magazine of the Industrial Workers of the World) on 30 July 1917, the fist emerges from the subsoil as a natural energy, pushed upwards by the mass of the workers’ arms. In the background, smoke billows out from various factories, a skyline of industrial production: this is a clear example of the fossil fuel aesthetic, so central to the shared imaginary of productivity and energy.[2] The hand is to work as oil or carbon is to energy. The raised fist looms large in the industrial landscape, a literal union of workers fighting for their rights. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Ralph Carlin, “The Hand That Will Rule the World”, Solidarity, illustration in the magazine of the Industrial Workers of the World (30 July 1917).

The fist: from the streets to the arts, and back again

Since the French Revolution, symbols, images and gestures have become crucial for the formation of collective political identities. These elements play a vital role in turning the masses into “movements” – that is, public protests need to have at least a semblance of structure, so that the crowds are not perceived as a mere unwieldy rabble, which in turn might justify the exertion of violence upon them by the supposed defenders of the social order. The “masses” are not only a category, and joining forces in this way is also a fundamentally political strategy of the many against the few, an attempt at redrawing the political map in all its emancipatory potential.[3] The raised fist can be inserted within this political tradition and, as we will see, it became one of the key signs for the internationalist labour movement.

From the early 19th century, different representations of the protesting masses began to appear in illustrated magazines and paintings. The raised fist is part of that group of “lifting” gestures, to follow Georges Didi-Huberman, that exclaim a desire to “reveal one’s determination for life and liberty, in front of and for everybody, in the public space and in the time of history”.[4] However, the propagation of the raised fist as a rite of the masses can be attributed, at least partly, to the work of the artist-monteur John Heartfield, who used this image-gesture in his logo for the RFB (the Rotfrontkämpferbund, the Alliance of Red Front Fighters) in 1924. The founding of the RFB was the German Communist Party’s response to the right-wing paramilitaries, and it was a formally independent organisation, open to anybody who would take a stand against fascism and the imperialist war. It adopted the fist as its symbol, and members began to use it as a greeting in marches, rallies and conventions, following the group’s founding that same year. In this context, the raised fist was used as a paramilitary symbol, showing the communist workers’ anger, as well as their eagerness to combat the prevailing social democrats. It was already clear that the social democrats’ strategy would be to curb the more radical aspirations of the working masses, following the success of the Russian Revolution. The Communist Party wanted to declare their resolve to the working class, reasserting that they would not back down in this struggle.[5] Heartfield’s role in this process is proof of the transfer between events, bodies and images, in what is almost always a round trip: art produces images for the revolution, and, in turn, the revolution itself generates images that are then used in artistic production. As such, this particular fist transformed into a collective expression that spread far and wide, eventually becoming ubiquitous in the 1930s public space.

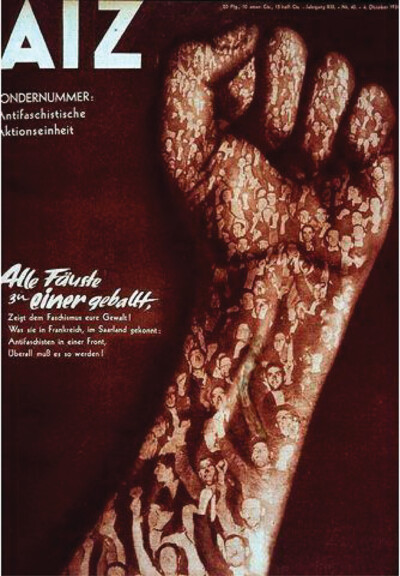

Figure 2: John Heartfield, cover of the AIZ, Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung [Workers’ Illustrated Magazine], no. 40 (1934).

Figure 3: Frontispiece of Leviathan engraved by Abraham Bosse, with input from Thomas Hobbes, the author, 1651.

In 1934, just a decade → after creating the RFB logo, Heartfield designed the cover for the 40th issue of AIZ (i.e. Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung, the Workers’ Illustrated Magazine), which was a special edition on “Antifaaschistische Aktionseinheit” (“United Action Against Fascism”). (Figure 2) In an inverted version of Abraham Bosse’s frontispiece for Hobbes’ Leviathan, the whole front page of the AIZ is taken up by a monumental arm and fist, in which a mass of workers are depicted with their own fists raised. Although, in the illustration for Leviathan, the individuals’ bodies are subordinate to the king’s head (in other words, the monarch is the rational one, who thinks on behalf of the anonymous → crowd) (Figure 3), in the case of Heartfield’s fist, the action itself is what rules over the multitude. The fist drives the masses forward. It seems to be an ode to movement, to action, to emulate Hannah Arendt’s political thinking, whilst in the Leviathan illustration it’s the complete opposite: the sovereign holds back the many, he appeases them. We should not forget that most of the criticism levelled at multitudes of people, even as late as the 1930s, came from the intellectualism as inherited from Gustave Le Bon’s theories on crowds, which he claimed were irrational and readily influenced by ulterior motives and depravity. It seems that Heartfield’s image aims to highlight the power of movement and action, a power which lets the masses break new ground. But perhaps the most striking difference between these two images is how the crowd is represented. In the Leviathan illustration, the individuals are repeated within the king’s body, and they lose all identity. Furthermore, they are depicted with their backs to the spectator, as if they are looking at the sovereign, the only one shown with a face, the only one there with any features. However, in Heartfield’s image the people in the crowd still retain their human condition, and we can even make out the features of some of them, especially those at the front. This consideration of crowds is crucial, because it humanises them and effectively shows the dual condition of the masses, whereby they are understood as a force for liberation and hope, but only if their individual identities are added together rather than being annulled and defaced. This particular crowd, multiplied within the arm, showed that the fist was now a rite of the masses. Undoubtedly, its expansion as an internationalist gesture was also partly due to the fact that illustrated magazines like this could help spread, throughout whole nations, not only political ideas and slogans, but also images (which are ideas and slogans in their own right). In his exhibitions, Heartfield would always display issues of AIZ alongside his original compositions, because it was important to him that his photomontages were not shown independently, as one-of-a-kind artworks – instead, he sought to reiterate that his work was widely reproduced in print media, in journals and posters, etc., and this is how they reached the masses.[6]

In the 1930s, it had become clear that the role of art and beauty needed to be loaded with new meanings. For a 1935 exhibition of Heartfield’s work, in Paris’s Maison de la Culture (described as an exhibition for dreaming, but also for clenching fists), Louis Aragon wrote “John Heartfield et la beauté révolutionnaire”, in which he stressed that the invention of the photomontage, by Berlin’s Dadaist group, was the ultimate challenge for painting. For Aragon, photomontage not only surpassed painting in its fidelity to reality, but it also loaded the gesture of montage with poetic intention. These poetic motives now had a new function, one that was closely related to the revolution:

[…] there was no more poetry that was not also Revolution. […] [John Heartfield] knows how to create those images which are the very beauty of our age, for they represent the cry of the masses – the people’s struggle against the brown hangman whose trachea is crammed with gold coins. He knows how to create realistic images of our life and struggle which are poignant and moving for millions of people who themselves are a part of this life and struggle. His art is art in Lenin’s sense, because it is a weapon in the revolutionary struggle of the Proletariat. John Heartfield today knows how to salute beauty. Because he speaks for the countless oppressed people throughout the world without lowering for a moment the magnificent tone of his voice, without debasing the majestic poetry of his colossal imagination.[7]

“John Heartfield knows how to salute beauty”, affirms Aragon, borrowing this expression stressing the “salute” from Artur Rimbaud’s Une saison en enfer (1871) [8]. Rimbaud, “the poet of the Paris Commune”,[9] sought to “change life”, and on the occasion of Heartfield’s exhibition Aragon referenced him to describe how the technique of photomontage was a space for rebellion and an instrument for transformation. This is the line taken by some proponents of the avant-garde, who understood art as the liberating energy of the people, thus sidestepping the bourgeois notion of art. When the multitude raise their fists, they repeat the gesture and establish a new relation of solidarity, in which the I, the self, becomes yet another subject, beyond individual subjectification. When the crowd reacts at the same time, amid the intersubjectivity of anonymity, a new form of je est un autre is produced, and takes place.

The expansion of the gesture as a sign of comradeship, internationalism and the global crowd

Another crucial factor in the expansion of this sign is that it does not need any “technology”, other than that of the body. The worker’s body incorporates the ideology. Raising a clenched fist is a simple, elementary rite, which doesn’t require any “technical” support and “lends itself to collective protest as well as individual pose”: the raised fist is already built into the worker’s body, who embodies the ideology by adopting the gesture.[10] Its expansion, from its conception as a paramilitary symbol for the RFB to its uptake as a mass gesture, became modified, progressively passed on to more and more diverse causes, in a process of the “civilisation of the rite”.[11] The gesture is transformed by the masses and not the other way round; the broadening of its uses is precisely what allowed it to become a transhistorical gesture, one that has since accompanied numerous defiant movements and many other emancipatory fights. The workers, mobilised en masse, would be the ones to endow the raised fist with meaning, imbuing it with emotion and transporting it with their bodies, over the course of their different struggles.

Subsequently, over the following years, the use of the raised fist gradually expanded in meaning and application, going from the German communist struggles to the Popular Front in France, and later in Spain. The rise of the Popular Front meant the construction of a unifying and symbolic bloc of different left-wing movements, essentially the grouping of the many who defended freedom and decried fascism. The Popular Front would become a space of fraternity in which political plurality could come together, like fingers when they fold over the palm to make a fist. However, the massive internationalisation of the raised fist would only come about with the → anti-fascist struggle in the Spanish Civil War, and the collaboration of the International Brigades, who used it as a greeting that transcended the language barrier. Geoffrey Cox, a correspondent for The News Chronicle, described the arrival of the first international militias in Madrid, in early November 1936, as follows:

The few people who have about lined the roadway, shouting almost hysterically, “¡Salud! ¡Salud!”, holding up their fists in salute, or clapping vigorously. An old woman with tears streaming down her face, returning from a long wait in a queue, held up a baby girl, who saluted with her tiny fist. The troops in reply held up their fists and copied the call of “¡Salud!”.[12]

From the tension that bubbles between dreaming and clenching the fist, as described above, a new form of community arises: a community that fights for a better world, offering up their own bodies to the battleground. It is a code to be used in the public space, with an abstract meaning that goes beyond words, brimming with the desire to build a community of equals. The I becomes we, a shift which is essentially the sense of belonging, as noted by the Russian revolutionary, socialist, → feminist, activist and intellectual Alexandra Kollontai (1872–1952). Jodi Dean has analysed how the term “comrade” is a generic description for a relationship of closeness, an affirmation that we are accountable to each other. More than defining a figure, a specific character or an identity, “comrade” describes a relationship based on equality:

The term “comrade” points to a relation, a set of expectations for action. It doesn’t name an identity; it highlights the sameness of those who share a politics, a common horizon of political action. If you are a comrade, you don’t publicly distance yourself, even a little bit, from your party. Comradeship binds action and in this binding works to direct action toward a certain future. For communists this is the egalitarian future of a society emancipated from the determinations of capitalist production and reorganised according to the free association, common benefit, and collective decisions of the producers.[13]

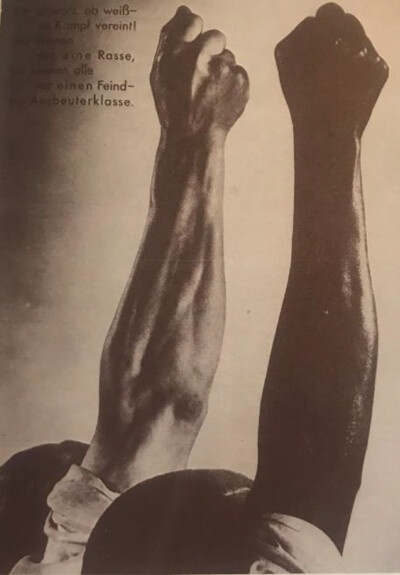

There is something fundamental, in this view of comradeship, that alludes to the gesture of the raised fist itself: this → solidarity comes about in battle. Comrades are not formed or united by their identity, but rather by their fight against an external enemy. Anybody, but not everybody, can be a comrade, and this accentuates the fact that the term “comrade” simultaneously unites and divides. It’s the same when people raise their fists in public: this action forms an “us”, as opposed to a “them”. It creates alterity and antagonism by means of a gesture. Acknowledging the power of the collective fight, of strength in numbers, is essential if one is to be freed from the chains of oppression and any form of slavery. Unity has great force, as Heartfield showed in his contribution to Issue 26 of AIZ magazine, a special edition called “Life and Struggle of the Black Race” (1931), which features two raised fists, belonging to a black worker and a white worker. The image is accompanied by the text: “Whether black, or white, / in struggle united! / We know / only one race, / We all know / only one enemy – the exploiting class.” (Figure 4) Ever since it emerged as a symbol, the entire iconography of the raised fist has been posited as an anti-racist gesture, as a call to transform the world from below, rallying against exploitation, racism and imperialism. In 1961, Heartfield paid tribute to Patrice Lumumba, the first black Prime Minister of the Republic of Congo, who was assassinated shortly after taking office. Heartfield published a poster using the same image of the two fists, but with a new text.[14] This is further evidence of how the raised fist was used as an internationalist sign, and important also in terms of decolonisation, as an emancipatory movement of the people.

Figure 4: John Heartfield, a cover of the AIZ, Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung [Workers’ Illustrated Magazine]: Life and Struggle of the Black Race, no. 26 (1931).

It is the gesture with which the placeless and nameless, as Jacques Rancière put it, can recognise each other. The streets become the setting for ideological struggle and social drama, a theatre of political passions. This spontaneity and discipline live on, today, in the gesture of the raised fist. It condenses a history, and it produces a memory of the working body in such a way that not only forges an emotional bond with peers in the present, but also with all those, over the centuries, who have fought for spaces of equality. In other words, it harks back to the many generations of workers who have called for a forward-looking community, sparking hope for a different world, where there are no social hierarchies or exploitation. This gesture thus situates all those who use it within history. In this performance of the social body, the subjects manifest a space of equality, based on comradeship and mutual support. As such, in the streets a proto-community arises, in which “the power of the weak” is dominant, led by those who normally languish at the bottom of the social structure.

In the coded symbolic semiotics of the raised fist, a common internationalist homeland is returned to the dispossessed. Internationalism can be described as a political horizon with emancipatory, progressive and egalitarian ends, with no → territory, and this is one of its fundamental gestures. As noted here, the raised fist rapidly became not only international, but internationalist. In the current protests all around the world, it has become an ever-present sign for the global crowd: it brings people together, in squares and streets, as they demand different forms of political representation, redistribution and social justice.[15] These protesters reconfigure the public space with their bodies, creating new appearances in images, thus raising awareness of the political potential of the body (and novel ways of using it in public) by merging activism and the most up-to-date visual languages. This, as I have noted elsewhere, is the shift from mass communication to the masses-who-communicate.[16] Distributing information in this way, and the resulting flow of images, sets up a context in which different people join together in a global crowd. Accordingly, images are crucial for internationalism, as they point to the demonstrators, those who shape the micro-politics out in the streets, as the driving force behind wider global movements. John Heartfield understood this perfectly when he decided to put his revolutionary aesthetic at the service of mass-distributed magazines.

The power of the raised fist, as a symbol, is due to the fact that it plays both an affective and effective role. This gesture is realised by the international worker, who embodies the internationalism described by Marx, but also by Bakunin. A common territory, without a homeland, in which only the subjectivised body of the proletarian exists.[17] It is the body that adopts gestures, that makes and performs the ideology in the public space. And it is aware of its international role. In this sense, the raised fist manifests the rage, hope and solidarity of the people. This small gesture contains all the necessary power and capacity for building a brand new world.