The Glossary of Commons needs to be thought of as a specific assemblage of critical terms that do not invite us only to reflect on the ongoing pandemic, but the deepening of the structural crisis that now spans through what has become of nature (imminent → ecological crisis), the capitalist crisis, crisis of neoliberalism, crisis of liberal democracy, and now openly waning system of US hegemony. There is then a unique historical moment today: the accumulation and condensation of contradictions and the uncontrolled nature of this and future pandemics/ecological crises, which means the situation has contingent and unpredictable outcomes. This new normal seems to become even worse, in a time when burning fossil fuels has become unacceptable, core countries are returning to coal production; draught and famine are worsening living conditions for increasingly large portions of the world population; a question of the politicisation of the “surplus population” – those segments that remain a reserve army of labour but still need to “survive” – becomes very relevant. In these grim circumstances, the last thing we should do is to either entertain a naïve technological hope (robotisation and digital technology will save us and at the same time we will enjoy a universal basic income – all without a serious struggle!), or to simply despair and accept the authoritarian turn with its fake news media outlets.

The key question of any critical glossary is not only to select, pick up and refine the specialised terms that relate to this unique situation, but if it aims to become useful and commonly used, it also needs to address the question of dissemination. What venues to use to present it, who will use it, or how to enable those who now riot, protest, organise, and so on, to dig through the relevant tools for further, socialised, common discussions?

Specific inter-related terms to propose: liberation (primarily political, but should be conceived more generally); and connected to a figure of community-in-liberation (figure of collectivity, stress on visualisation of “common” → solidarity).

In my recent book The Partisan Counter-Archive,[1] I worked on research into specific → anti-fascist and Partisan sequences, especially those related to the Second World War and the Yugoslav liberation struggle. This case study is specific, as it relates to the general conditions of war, fascist occupation and a struggle against local collaborationism and representatives of the old Kingdom of Yugoslavia (with both a civil war and revolutionary struggle). However, contrary to the dominant history that only narrates the past from the standpoint of a bipolar Cold War and its superpowers, we should insert a historico-political trajectory of those movements that carried the term and practice of liberation. To liberate in a radical way means firstly to depart from the causes of the crisis, while in more concrete political circumstance aim at stopping occupation. In the case of military-political occupations, be they fascist, colonial, or imperial, any gesture of resistance is immediately met with repression, and often death. In this respect, the sovereign power is brutal and defines most of all the relation between the border of life and death. Biopolitical/racial inscription is one dimension of its brutal force, and another is political resistance of the subject of liberation.

Furthermore, if the appendix history, academic curiosities, and former memory of Europe hailed anti-fascism (and to a lesser degree, anticolonialism) as a cornerstone of the post-war reconstruction, then these narratives long ignored the scale and → temporality of anti-fascist and anti-colonial struggle: in the case of anti-fascism it started as early as in 1920 with the rise of fascism in Italy, where Slovenian, Croatian and also Italian communists, patriots, and others organised anti-fascist organisations, while fascism was not beaten in Europe until the mid-1970s, lingering in Greece, Spain and Portugal, and continued in colonial terms outside of Europe for a while longer. In terms of anti-colonialism the struggle is not yet finished today, despite South African apartheid coming to an end in the 1990s. Liberation has never been a closed and finished process, especially if it is defined beyond the end of the occupation.

Moreover, all these views and histories of specific liberation experiences emphasise, as the name indicates, the prefix “anti-”: the latter emphasises the negative relation to the world, so we then speak of the fight against fascist and colonial occupation, the fascisation and colonisation of specific societies, of the world itself. This is the urgent matter, one forms a specific collective – we – that resists blatant injustices and occupation, and would (un)consciously relate to the specific definition of negative freedom (cf. Isaiah Berlin[2]) and the famous term “freedom from”.

What should be the emphasis or greatest goal is that any liberation – Partisan, anti-fascist, anti-colonial, people’s, national, women, planetary – should entail liberation for “commons”. In other words, liberation always carries a positive dimension, it develops the programme during the liberation struggle itself. The programme is thus not a recipe, but is instituted together with all resisting subjects and bodies, and thus it becomes more palpable, organised, taken on the scale of “social reproduction” that counters the dominant strategies of division in global capitalism. Liberation became in past – and can also become in our near future – a positive transformative project. If the glossary of anti-fascist and anti-colonial struggle succeeded in framing a more longitudinal concept, then it was grasped in the term “national/people’s liberation struggle(s)”, which had its strong echoes in discussions and revolutionary practice in the late 1960s and 1970s. These struggles did not want to fight only for the land/soil very present in the telluric moment, a trap of Carl Schmitt that plays on the Blut und Boden ideology, but also freedom, and liberation process that was more all-encompassing, and openly challenged a substantialist/ethnical definition of people/nation. Back in the 1970s Antonio Negri rehabilitated the figure of the Partisan/liberation struggle in the following way:

We began to understand how the freedom won in the fight against fascism and the German Occupation had been achieved by men who shared our feelings, who didn’t just fight against something but rather fought for a new world, one that they wanted to seize by making, experiencing, constituting, and creating it.[3]

This positive moment of “liberation” then relates to the work of the masses – not only intellectuals or the vanguard party – as it carries the moment of “subjectivisation of the masses”. It should start as an openly political process that speaks of constituting new political institutions of mass democracy, new aesthetic sensitivities and cultural (re)empowerment, and thus enable a specific and lasting encounter between the masses and any organisation that fights for the commons, the encountering of politics and art, and finally a new relationship with the commons, their reproduction and distribution. This demands a kind of maximalist ethics that does not concede to mere reform, to translate it, to only reform the colonial world, make fascists more human, and the capitalists exploit us a bit more nicely – no, this world pushes the majority into highly precarious and volatile environments, in which life becomes a series of strategic investments made by corporations and new sovereign lords. The struggle for liberation for a new commons then needs to set the most ambitious goals. If we could refine this in terms of the (aesthetic) figure and strategies of liberation, then what would be the figure of freedom/liberation today? However, perhaps it would be better to start with the “subject” of liberation itself.

b.) Figure of collective/solidarity/community-in-liberation

Marx and Engels’ slogan from The Communist Manifesto (1848) “Workers of the world, unite!” carries a strong prescription, one with a political, economic, and also aesthetic nature. As Soviet montage practices showed, it is possible to → translate this slogan in ways that formally visualise the subject in the process of becoming. Proletariat was and is a future subject, which will only emerge through political and artistic struggles. It will also not reside only in the sphere of production. Let’s take the fascinating example of Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, that not only visualises communism in the equality of different activities that are organised by the people and party, but rather Vertov succeeds in demonstrating an equality between reproduction and production. Then, at least from the avant-garde onwards, it became a matter of urgency in form and content to make, constitute, and re-narrate a subject, a new figure – the collective/masses/community-in-resistance-in-liberation.

This is of even greater urgency today, because of the decades of neoliberal individualisation that have seeped into resistance strategies themselves, and thus the figure of the collective, the figure of the struggle for the commons, needs to be re-imagined, and the possibility to imagine a new world then arises. Therefore, instead of the insistent fall into commodification and sticking to great (individual) figures of art and the politics of liberation, perhaps it is finally time to locate both in the past and present different strategies and artworks that ruptured with the dominant cannon/regime of saying and seeing. What I have in mind is a famous figure from the Yugoslav liberation struggle: a heroic man, woman, the figure of a woman (as a maximalist figure of liberation), and empowerment of the collective.

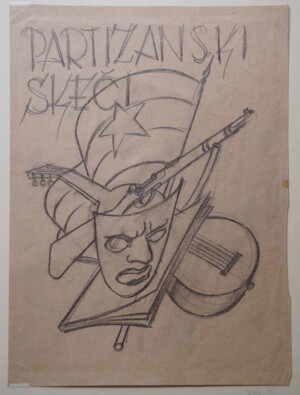

In the analysis of visual material, the core point would be in the following work by Dore Klemenčič, entitled Partizanski skeči (Partisan Sketches) that he drew in mid-1943. (Figure 26) The drawing that was supposed to become a poster is not a sketch of an individual Partsan figure, nor a caricature of the kind that Klemenčič practiced drawing throughout his time in the Partisans. Instead, this poster stands out from his opus since the work displaces the individual Partisan into an abstract realm of various Partisan activities. Klemenčič’s poster-to-be succeeds in sketching, thinking and commemorating the entire modality of the struggle. The poster-to-be complicates the more generally expected and accepted canon of the Partisan figure: one of a male or female fighter adorned with guns, smiling and at times with a star on their hat. This poster represents the fully armed and empowered Partisan struggle that redefines the notion of a weapon in war: from the obvious rifle to a guitar, a theatre mask and a book assembled under the new flag of the new Yugoslavia, which carries a star. The poster expresses the equivalence of the different arms used in struggle and puts on display a deeper solidarity among political, cultural and military work that aims for liberation and universal emancipation. This → lucid transfiguration, therefore, displaces the individual Partisan figure as the holder and bearer of plural Partisan activities, while the main protagonist becomes the struggle itself.

Dore Klemenčič, Partizanski skeči [Partisan Standups], mid-1943, poster draft. Courtesy of Janin Klemenčič.