According to Henri Lefebvre in The Production of the Space, the principles of institutions are repetition and reproducibility.[1] The terms according to which we interact with institutions (museums, libraries, prisons, hospitals, and so on) are thus based on the naturalisation of specific actions. This was finely designed by the museum during the Enlightenment, providing models of bourgeois public behaviour for cultural institutions. These terms were based on the apparent neutrality of the museum and the exhibition space, which were questioned by Brian O’Doherty in his classic Inside the White Cube.[2] Even though many artist and critics have analysed the ideological structure of the “→ white cube”, I would like to focus on those that had approached the issue from “the dark side”. Fred Wilson, for example, in his 1992 key project Mining the Museum, posed fundamental questions in order to imagine a non-reproductive institution, one becoming from below. That institution would dirty the whiteness of the museum. Questioning the false transparency of vision in the museum allows us to imagine an institution that assumes the abject, the possibility of contagion and, as a place of becoming, the confrontation against Western disciplinary structures.

The concept of “darkroom” involves a reinvention and erotisation of the institution; a revolt against the illuminist conception of the museum as a bourgeois public space based on the control of the social interactions of people. In the museum you cannot dance, you cannot be dirty, you cannot sleep, you cannot fuck. This imagination of a “museum of darkrooms” should be addressed from, at least, three starting points, which belong to three different, even contradictory, traditions, informed by colonial and feminist theories.

I.

Firstly, the darkroom allows us to conceive the institution as an architecture of desire. This pulsion-based architecture eschews disciplinary instructions, assuming the abject spaces of → deviant desire. A queer space: a perverse, useless, amoral, sensual, experiential and obscene space. It is a queer space that, as Aaron Betsky says, “instead of references to buildings or paintings, instead of a grammar of ornament and syntax of facades, here was only rhythm and light”[3]. It is the place for the hidden geography of the abnormals who use the normalised architectures of social life to construct their reverse. In Foucauldian terms, it could be a “place of liberation”, a political space for transforming living conditions in modern cities. The transformation of parks, public toilets or other modern institutions occurs as the opposite of the evident and normed: it happens mostly in the dark. As the Spanish artist Pepe Miralles says: “darkness is the ally needed for sexual interaction: light is heterosexual, darkness is the habitat of vampires”.[4]

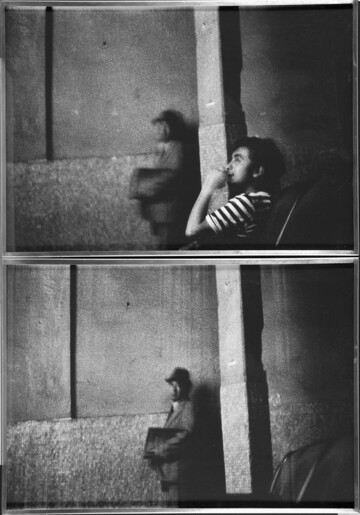

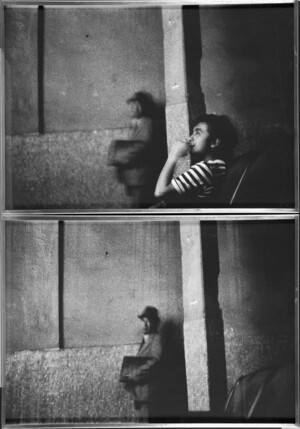

Figure 1: Miguel Ángel Rojas, Faenza series – Antropofagia, 1979, five black and white photographs on aluminum, 50 x 70 cm each. Courtesy of Museo Reina Sofía.

Those spaces of vampires are, in sexual terms, the places of cruising. The Colombian photographer Miguel Ángel Rojas took pictures – and developed them in a photographic darkroom – of the sexual subculture of the Faenza theatre in Bogotá during the 1970s. (Figure 1) Almost at the same time, Alvin Baltrop did it on the piers of Manhattan. Those cruising areas where spaces of freedom and sexual liberation, but at the same time were places of social interaction, generating microsystems that confronted the standardised system of the → family, monogamy and bedroom. Finally, these photographs register the possibility of assuming the insecurity of public space, something that has been completely erased by the cultural dispositives of modernity, as is the case of the museum. Those public places have recently mutated, as the Chilean artist Felipe Rivas San Martín has shown in the work Cabina (2012), where he presents the way modern public spaces have taken a new camouflage: places such as bars or internet cafés, and more recently mobile applications, that are explicitly made for sexual interaction.

Figure 2: Roberto Jacoby, Darkroom, video still, 2005. Courtesy of Museo Reina Sofía.

In a more experiential way, the Argentinean artist and sociologist Roberto Jacoby used the metaphors of the darkroom on his homonymous work from 2005, that was presented in 2011 at the vaults of the Reina Sofía museum. He showed a series of video recordings of a performance that was held in complete darkness, visible only through a night vision camera, where different sexual and non-sexual situations occurred. (Figure 2) In a different sense, this approach was used by the Spanish artist Andrés Senra in his ongoing project Cruising, common and queer psychogeography, developed as a critical approach to Madrid’s upcoming World Gay Parade. By using different technological devices he proposed tours to cruising areas, taking the bodies of others as well as your own as places of the → commons, open to multiple uses and possibilities of transformation.

II.

Secondly, we can approach the darkroom considering the ideas of the French feminist thinker Luce Irigaray, who developed some concepts that confronted the phallocentric structure of modernity. In the book Speculum of the Other Woman, she proposed the reinforcement of the concept of opacity and the phenomenon of the labyrinth. Both concepts were conceived as epistemological experiences of the interior of the vagina. Where Freudian theory had seen an absence of the phallus, she argues a reinvention of the experience of the interior as a space full of folds. The turn of the speculum of gynaecology was proposed not as a medical instrument, but as a breaking off with regard to the supposed universality of the gaze: the tactile experience is a micropolitical experience that never tries to have an overview of a phenomenon but a fragmentation. In this sense, women are “the opacity yet non-differentiated of sensitive material”[5].

In 1992, the American former sex worker Annie Sprinkle entered into the art world through her vagina. With the performance Public Cervic Announcement she showed to the public the interior of her vagina, making a more tactile and intimate relation between the public and that work of art. In her more recent projects, she has continued dealing with the paradox of medical discourse and, in an ecological turn, has worked on the idea of “making love to the earth”, introducing sex and nature intro an erotic setting inside or outside the museum. Other Latin American artists, such as Johan Mijail or Fannie Sosa, have worked on this idea of a “natural love”, but in their case related to indigenous, negro and mestizo religions on the continent.

Other artists, in particular in the queer scene of Barcelona, have worked on a displacement of Sprinkle’s concern with the vagina to the anus. María Percances and Jordi Flecos have developed in different contexts the project Arte enANO, that can be translated at the same time as “small art” and “art in the anus”. In their projects, Percances changes at different moments the images shown of the interior of her anus. The same can be said of different projects developed by Mariokissme, where he uses the anus either as a site of pain or as one from where it is possible to listen to music that reflects the colonial and contemporary tensions of sodomy. In this sense, these artistic practices have expanded the complexity of the vagina to the anus as a key space of → the contemporary that has been privatised by modern medicine.

The invention of an institution that assumes the contemporary chaos becoming the interior of the vagina and the anus makes them productive in a revolt against the Western logoculocentric experience of the museum. We should remember that Irigaray criticised Derrida’s analysis of logocentrism, as he did not recognise its intrinsic masculine structure. The phenomenon of the labyrinth, in contrast, rejects transcendental meanings and the perception of truth as a masculine → universalism. The “femina vita”, as Irigaray called it, hides the truth and assumes the second sex traditionally posed as a revolt. It is then the reinvention of a knowledge produced by pulsions before symbolic language: against beauty and clarity, precise definitions and perfect forms. The dark continent of femininity assumes the lack and reinvents it from the memory of the fluids of milk, tears and menstruation.

III.

Finally, there is a third possible approach to these dark continents considering Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui’s concept of ch’ixi. This Aymara word refers to a place where white and black can never give birth to pure grey. The ch’ixi mix operates not by subsuming but juxtaposing concrete differences. It works as an image to think of the coexistence of heterogeneous elements that don’t produce something new and closed. Whereas Walter D. Mignolo launches the idea of the “dark side” of the Renaissance[6], Rivera Cusicanqui takes a transhistorical turn in order to think of the place of the “encounter” as an insoluble problem. Particularly, she refers to the contemporary colonial conflict, considering that the trauma of the conquest in the Andes is still alive in multiple bodies.

In artistic terms, we can relate this idea to the Mexican artist Pedro Lasch. In his project Black Mirror he generated a conflict of language and opacity juxtaposing, without a hierarchy, pre-Columbian sculpture with images of modern Spanish paintings.

IV.

Figure 3: Marica Multitude. Activating sexual-dissident → archives in Latin America, exhibition view, 2017. Courtesy of Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende.

From these three different points of departure the main question that it is still open is how not to “represent” sexual and racial dissidence, but to “transform” the logics of institutional spaces. How to imagine a darkroom that confronts the false neutrality of the Western hetero-enlightened museum. How to imagine an institution that hosts the danger of desire and the risk of the contagious, confronting its modern disciplinarity and assumed neutral hygiene. We have rehearsed this in the exhibition Marica Multitude. Activating sexual-dissident → archives in Latin America at the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende. The art works, the museography and the debate spaces have been conceived as darkrooms, including different experiences beyond vision, such as smell or touch. But there is always a gap, and the structure of our own unconscious relation with the museum needs more exercise in order to make whiteness explode. (Figure 3)