The notion of “alignment” almost automatically evokes the idea of space. Concretely, it invites us to think of taking a certain position within a geopolitical space. But the fact is, however, that the term “alignment” as such does not at all belong to the vocabulary of geopolitics. It is rather its negation that more than a half-century ago entered the political stage of the world. The so-called → Non-Aligned Movement was founded in the midst of the Cold War at the first Conference of Heads of State or Government of Non-Aligned Countries, held in September 1961 in Belgrade, the capital of what was then socialist Yugoslavia. It was initiated by Josip Broz Tito, then the President of the country, and attended by Jawaharlal Nehru of India, Sukarno of Indonesia, Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana. Soon over 100 countries, mostly from the Third World, joined the Movement, which played a significant role in international politics in the second half of the 20th century.

Today, none of the founding fathers of the Movement is still alive. The country, where it was founded, Yugoslavia, fell apart in a civil war, without any of its successor states showing → interest in the legacy of the non-alignment. Yet the Movement itself, although having lost any significant influence on international politics, has curiously survived the end of the Cold War, in opposition to which it had once found its raison d’être. This, however, seems to be changing now.

Since Narendra Modī took office as India’s prime minister in 2014, the world’s second-most-populous nation, and one of the founding members of the Non-Aligned Movement, has openly abandoned non-alignment as the guiding principle of its foreign-policy. The change is even more significant if we remember that it was in fact an Indian, V. K. Krishna Menon, who in 1953 coined the term “non-alignment”. Yet another Indian, Jawaharlal Nehru, was first to define it as a geopolitical concept based on five principles: mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty; mutual non-aggression; mutual non-interference in domestic affairs; equality and mutual benefit; peaceful co-existence.

But today India’s prime minister has a better idea, something he calls a “multi-alignment policy”. Behind what some commentators not without irony call a “grand vision” there are no more regulative ideas in the tradition of Kantian “eternal peace”, but rather a very pragmatic idea of doing business with all. Without abandoning its independent course, India has moved to a contemporary, globalised practicality, according to which it will carefully balance closer cooperation with the major players in today’s global geopolitics, like US, Russia or China. It has been doing it in a way that advances the country’s economic and security interests, without being forced to choose one power over another.

As long as a particular vision of international politics was based in no more then pure negativity to alignment, there was no need to introduce the term into the vocabulary of geopolitics. But now, after the non-alignment has been turned into a multi-alignment claiming similar strategic vision of international politics there is obviously sufficient reason to conceive of “alignment” as a new concept of the contemporary geopolitics.

This change in the vocabulary of international politics corresponds, however, with the change in the perception of historical reality, or more precisely, it implies a new “grand narrative” of recent history, a narrative that makes sense of particular political decisions, causally connects them and depicts a broader historical picture in which these decisions are made. Such a narrative, in which the aforementioned turn in the general strategy of Indian foreign policy from the old principle of non-alignment to the new one of multi-alignment, appears as a symptom of a much deeper historical transformation, is offered in Immanuel Wallenstein’s short essay “Precipitate Decline: The Advent of Multipolarity” published in 2007.

As the title already suggests, the emergence of a new paradigm in today’s international relations, the so-called multipolarity, reflects a very concrete historical process, the decline of the United States of America, which, according to Wallenstein, has become apparent only after the fiasco of the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Contrary to most analysts who see the United States hegemony in the world-system at its peak in the post-1991 era, the era dominated by another paradigm of international relations, the unipolarity, he argues that this hegemony has been in decline ever since 1970. In fact, he tells a generally different story of the last hundred years, not one of the two World Wars, but of the “Second Thirty Years War” from 1914-1945, a concept that was introduced in 1946 by Charles de Gaulle. For Wallenstein the principal antagonists of this single 30 years war were the United States and Germany. According to his view, the USSR was only militarily assisting in the victory of the United States 1945 with which began the period of its unquestioned hegemony that lasted until 1970. It was a period in which the United States absolutely dominated the world-economy as its most productive and efficient producer. It turned its former enemies, Germany and Japan into its political satellites and struck a deal with its sole challenger, at least on a military level, the Soviet Union. According to the agreements in Yalta, the world was divided into two blocks, which respected its clearly demarcated boundaries. Despite many crises, which often culminated into local wars, like in Korea, Vietnam or Afghanistan, the military status quo between two blocks guaranteed a long-lasting global peace, a peace that was, curiously, called war, or more precisely the Cold War.

Wallerstein argues that already by the mid-1960s both Western Europe and Japan had reached virtual economic parity with the United States, which had no longer any particular advantage over its allies. At the same time, the countries and political movements of the developing world, for whom the Yalta deal had not brought any significant benefits, started to pursue their own → interests. This was politically articulated in the form of a struggle for national liberation that often had a clearly → anti-colonial character. Wallerstein sums up this political process under the name of “the world revolutions of 1968”, meaning the multiple revolutions that occurred between 1966 and 1970.

This is where we should situate, both historically and in terms of a transformation of the world system, the emergence of the → Non-Aligned Movement. It was generally a revolt against the neo-colonial and neo-imperial order, which concretely targeted a political arrangement that brought this order into being and guaranteed its persistence, the Yalta deal and the bipolar logic of global power-relations.

These two historical events, the coming of the Non-Aligned Movement on the stage of world politics, as well as the “the world revolutions of 1968”, also mark the historical moment at which, according to Wallerstein, the structural decline of US power and authority in the world-system began. It was a new reality of which those in power in the United States soon become aware. Wallerstein argues that the key objective of all presidential regimes after the1970s, from Nixon to Clinton, was nothing more than to slow down this decline. As one of the consequences of the series of structural adjustments that US politics has undertaken ever since – making of the former satellites, Western Europe and Japan, partners in the implementation of common world policies with whom it works in various international institutions, from the Trilateral Commission and the G-7 to the World Economic Forum in Davos – the new geopolitical order has emerged, an order we might call “multilateralism”. At stake is a new global condition in which, as Walenstein writes, “the United States has been reduced to the position of being one strong power in a multipolar world.”

But this is also a condition in which the alignment, or should we say, the politics of alignment, becomes an imperative, although it is not felt as such. The decision to align is made today as a matter of rational choice. And it is made everywhere, not only on the geopolitical level. One cannot see oneself as a member of a community if this community is at the same time not seen as a member of something else, of another, larger community aligned around a so-called value, a cultural or religious identity or simply an interest. The urge to align seems to have become a driving force of social being, not one of its affects that regulates external relations of a society and is activated only after this society has already ben created, but a sort of condition of its possibility that precedes and facilitates its very formation and assures its inner consistency and historical reproducibility. To be social today means to be always already aligned. And since becoming social is always already a matter of becoming political, alignment is a political issue or even better, an issue of the political, that is, an issue of creating society and bringing into existence the social being as such.

Yet the multipolar world in which alignment no longer follows some universal principles grounded in a vision of a more just world, free of war, but has become instead a matter of “rational choice” led by egoistic interests of a particular country or its current government, is far from being a world of social stability and peace. On the contrary, ever-larger parts of the existing geopolitical order deteriorate into a sort of permanent state of exception in which the former social contracts appear to be dissolved forever. These new spaces of disorder, lawlessness and violence generate new forms of social misery, economic regression and political extremism, which can no longer be contained outside of the actually existing democratic order. As a consequence, the old bastions of socio-political stability come under increasing pressure from no longer controllable migration and the greater threat of terrorism. Only two decades ago there was a widespread feeling that the world had entered a permanent state of peace, and this idea is now severely shaken. Even the vocabulary of geopolitics (and Wikipedia too) has reacted to the new reality. It has coined a new concept, the notion of “The Cold War II”. The idea, which is also known as “The New Cold War” and the even more sinister “The Colder War”, refers to the renewed tensions, hostilities, and political rivalry that intensified dramatically in 2014 between the Russian Federation on the one hand, and the United States, European Union and some other countries on the other. The tensions escalated in 2014 after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its military intervention in Ukraine.

So the Cold War is back, moreover, the geopolitics is back on the agenda.

At this place we should come back to what Wallerstein calls “the world revolutions of 1968”. Not only did they denounce the Yalta deal; they also denounced “The Old Left”, the traditional anti-systemic movements comprised of three components, Communist parties, Social-Democratic parties, and national liberation movements, and which Wallerstein defines as having a two-step strategy: first to conquer state power, and then to change the world. The revolutionaries of 1968 concentrated primarily on the second step, to change the world, which has become a differentia specifica of the New Left.

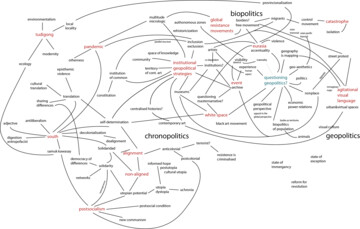

Yet today when it comes to the politics of the global Left, both practically and in terms of its historical visions, it is not difficult to diagnose certain deficits. According to Alberto Toscano, in the last 25 years the Left has almost completely ignored the geopolitical perspective. Totally devoted to all sorts of so-called struggles for hegemony, mostly in the realm of culture and education, as well as socially focused on the sphere of civil society, it has forgotten, as Toscano argues, that geopolitics frames the conditions of a political action, especially in terms of a politics of radical transformation, → emancipation or revolution. Geopolitics situates all these struggles into the reality of geopolitical constraints like economic competition, scarcity of resources, biopolitics of population or military calculations.

The old anti-imperialist, anti-colonialist Left, including the left involved in class struggles, was much more realistic and was concretely involved in instrumental geopolitical calculations. Toscano calls this “battle-hardened realism” and argues that it disappeared from the strategy of the Left after 1989/90, i.e., after the fall of historical communism. It seems as though the Left for more than 20 years completely accepted the proclamation of historical closure and liberal-democratic hegemony, and thus Fukuyama’s turn to so-called post-history in which no historical move is imaginable outside the ultimate horizon of capitalism and Western liberal democracy.

Yet this is changing now. The circle of historical idleness and immobility is finally closed. If the Cold War is back, the geopolitics too should be back on the left-wing agenda, and with this, the drama of alignment as well.