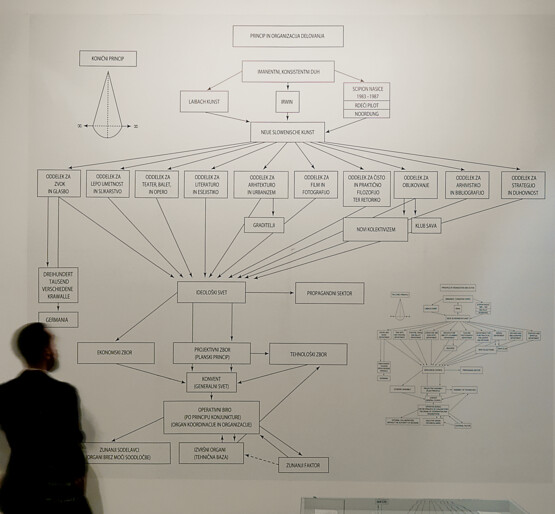

NSK’s interrogative rematerialization of ideology in the field of the visual assumesspectacular form in the 1986 “organigramme” (NSK organizational diagram). In1987, Laibach described it as follows: “The NSK organigramme (organizationaldiagram showing principles of organization and activities), which has been madepublic several times on several occasions, clearly shows the hierarchical structureof the Body. In the head of NSK we cooperate on equal footing with Irwinand Cosmokinetic Theatre Rdeči pilot in a tripartite council led by the ICS (theimmanent, consistent spirit). The collective leadership is rotational, the membersare interchangeable. The inner structure of the Body functions according to theprinciple of command and symbolizes the relationship between ideology and anindividual. Inside the Body there is equality. It is absolute and indisputable, andis never questioned by the Body. The head is the head, the hand is the hand, andthe differences between them are not painful.”

The organigramme reflects trends toward self-institutionalization within theLjubljana alternative scene of the period. Artists, curators, punks, and otherswere all dissatisfied with the “official” cultural institutions, but rejected the clandestinestatus of extra-institutional dissidents. The Slovene alternative was basedon institutions and self-definition, both within and outside existing structures.This process of institutional proliferation represented an extrapolation of theimplications of the self-management system, using its formal emphasis on selforganizationas a source of legitimacy to create a contra-systemic dynamic. Boththe new institutions and NSK manipulated the system and its ideology to defendrelatively autonomous activities. Institutions such as ŠKUC were at the far autonomousend of the spectrum of state organizations, but the creation of NSKas a wholly autonomous cultural alliance represented the culmination of trendstoward self-institutionalization.

The organigramme took the process of alternative institutionalization to its (il)logical formal extreme, recapitulating and attempting to transcend the institutionalanarchy of the period and the fantastically complex, deliberately opaque web ofstate and parastate organizations within the late Yugoslavian system. In 1990, theBritish authors of the last full edition of the Rough Guide to Yugoslavia observed. “Diagrams of NSK’s organizational structure bear a striking resemblance to thosein Yugoslavian school textbooks which seek to explain the country’s bafflinglycomplex system of political representation.

”The organigramme appears to symbolize the traumatic return of an inhuman,mass-organized totalitarian state. However, its significance did not end with thecollapse of the Yugoslavian system, or the fall of Communism. Like many other NSKworks, it looked forward as well as (because of) backward. Its menacing qualityrefers not just to the states of the past but to the political state of the present, toa period marked by the dominance of the corporate ideologies decoded by NaomiKlein. Branding experts’ talk of the “souls” or “consciousness” of corporationsbetrays the continued manipulation of the mystifying and potentially hypnotic effectsgenerated even by the most faceless and technocratic organizations. Theseeffects are as characteristic of organized religion as of totalitarianism or capitalism.Just as Deleuze and Guattari argue that, consciously or otherwise, Kafka’s work216 sensed the “diabolical powers of the future” (among which they listed Americancapitalism as well as Nazism and Stalinism). NSK, too, may have detected thecorporate future as much as exposed the present, recapitulating the stimulationof audience responses to produce “brand loyalty.”

More works at the NSK from Kapital to Capital exhibition in the EXHIBITION GUIDE.