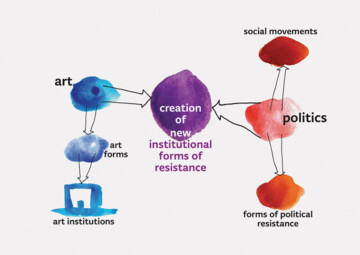

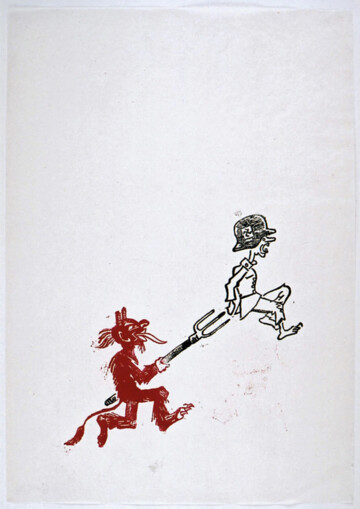

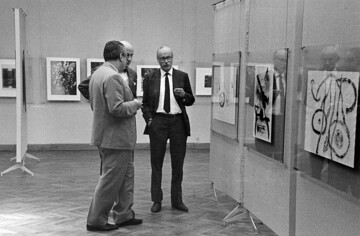

Speaking about the emancipatory potential of national resistance, economic transformation and new forms of internationalism from the perspective of former Yugoslavia we should emphasize the three historical sequences (which some political philosophers address as “politics of rupture”); something that was completely different from the established state politics in Yugoslavia of that time, and those three sequences were the Partisan liberation struggle, self-management, and the non-aligned movement. But when we discuss the emancipatory potential of these historical sequences, we also have in mind the specific cultural production of that era, which was inevitably linked to the social revolution and which had a deep impact on the cultural politics in Yugoslavia after the Second World War, especially after Yugoslavia’s break with the Soviet Union. The question is: why were these “cultural revolutions” in the former Yugoslavia so significant? One of the answers could be because they not only transformed the inner order of culture or the position of the cultural sphere in social structure, but, as Slovene sociologist Rastko Močnik suggests, because they attempted to eliminate the cultural sphere, which by its own existence embodies the “barbarity of classes”, and re-established culture in the sphere of human emancipation. Here we have in mind, for example, the Partisan art of the second world war where art did not only involve “the masses” in the process of artistic creation (illiterate partisans, men, and women, not only learned to write – they wrote poetry) – but also: art and politics traversed the resistance movement and the social revolution. As our colleagues in Ljubljana wrote: the art produced in relation to the partisan movement was actively involved in the movement’s transformative process by being itself subjected to it: it contributed critically to the articulation of the struggle’s symbolic coordinates, which also dictated that art is self-critical. After the break with the Soviet Union a particular success, if we may call it that, was the introduction of self-management in the cultural sector. In a specific way, the 1950s were a period of cultural blossoming in the former Yugoslavia. For example the formal status of a freelance cultural worker was introduced, part of the national budget went towards numerous cultural activities, modernism was introduced as the favored style, etc. Some of the main concerns of Yugoslav cultural policy at that time were including culture in the entire socio-economic context and transforming citizens from passive users into active co-creators of culture; which is definitely something that could also be observed today in the context of the “commons”. Already in the 1950s socialist Yugoslavia, the emphasis was placed on the educative function of culture rather than on the artistic one, and museums were encouraged to address the entire working population, that is, the spheres of economy, education and culture were transferred to the people themselves. That was what the idea of self-management was about – every worker was brought into the decision-making process, including in culture. There the workers were called cultural workers. What we are interested in are the elements, traditions, references from those past experiences that can be extracted or recuperated in times of neoliberal capitalism. How applicable these ideas are for the development of international solidarity in the sphere of culture, new models of cultural and knowledge production today? What are its emancipatory potentials? And most importantly: How to recover the lost and forgotten ideals of the three historical sequences mentioned at the beginning and how to translate them into praxis?