This short intervention is founded on a hypothesis that in many parts of the globe we are facing an imminent threat of resurgent fascism. I will argue here that to counter fascism, we have to connect and strategise on an international scale, while alleviating failures of neoliberal globalisation. As an art worker myself, I will signal the urgency to discuss and transform the ways in which contemporary art is practiced, instituted, and globally circulated, so that it can partake in engendering new, anti-fascist international. This short text is driven by hope that even though neither art workers nor art institutions are able to establish such anti-fascist international on themselves, they are able to enter into existing alliances and create new ones, productively contributing to new popular fronts against resurgent fascism.

Even though the Glossary is not a proper place for an academic discussion about the nature of recurrent fascism, a brief reconstruction of this heated debate is in order. Purposefully, I frame the return of fascism as a political and theoretical hypothesis, as the nature of this return is disputable. Philosophers like Renzo Traverso or Gáspár Miklós Tamás emphasise the specificities of the current authoritarian tendencies, preferring to call them post-fascist instead of relying on fuzzy analogies to European 1930s. Also, fascism is often dissected not as a phenomenon of its own, but rather an expression of other, fundamental tensions created by economic, racial, gender, or ecological oppression. So fascism can be deconstructed in the context of colonialism, following Aimé Césaire and Hannah Arendt, as a boomerang effect of European violence that strikes back former metropolis. Feminist scholars emphasise the patriarchal and masculinist character of resurgent fascism, and draw from the feminist tradition to counter it. One can also sensibly analyse the role of neoliberalism in creating structural conditions for fascist revival, and dissect the anti-ecological character thereof.

Fascism is patriarchal, it is fed by injustice, it is imperialistic and militaristic, it is a murderous and fundamentally irrational response to the climate crisis. Still, in my opinion, fascism cannot be reduced to any of these tendencies, taken in separation, as it is propelled by a death drive that transcends them. In this, I agree with a philosopher Michał Kozłowski, and other activists, artists and thinkers, who argue that it is essential to call out fascist tendencies for what they are. This intuition was forged in a daily experience of anti-authoritarian struggles in Poland, and involvement in instituting a nation-wide coalition of art workers and artistic institutions responsible for organising the Anti-fascist Year (2019-2020). When I posit that fascism exists and has tremendous implications for both art and politics, I refer Umberto Eco’s concept of Ur-fascism. According to him, despite the eclecticism and incoherence of every particular fascist regime, all fascist movements, organisations, parties, and identities share a wicked family resemblance. According to him, the Ur-fascism or eternal fascism includes such characteristics as cult of tradition, the rejection of modernism, the cult of action for action’s sake, labelling disagreement as treason, fear of difference, appeal to social frustration, the obsession with a plot, painting the enemy as both strong and weak, reverence of violence, machismo, cheap heroics, selective populism based on newspeak, contempt for truth, reason, and artistic freedoms. As Eco argues, every fascist regime does not need to tick all these boxes, and yet most do. Fascism as such is an eclectic, incoherent, often self-contradictory amalgam, driven by the lust for power and underpinned by a death drive. And precisely this tendency resurfaces in every corner of the globe, as analysed in the special issue of the FIELD journal, edited by Gregory Sholette, dedicated to Art, Anti-globalism, and the Neo-authoritarian turn (2018). It features reports from all over the globe that evidence the international backlash against democracy, equality, and emancipation. Yet, the examination of Ur-fascism should not devolve into a blanket judgment or a swear word, neither should it provide an intellectual excuse for not facing the complex reality as it is by engaging with sloppy analogies to historical events. But it remains theoretically insightful and politically pragmatic, to identify and counter fascist tendencies, while celebrating and reviving the legacy and achievements of anti-fascist struggles worldwide. The art workers and artistic institutions alike are able to productively contribute precisely to this task.

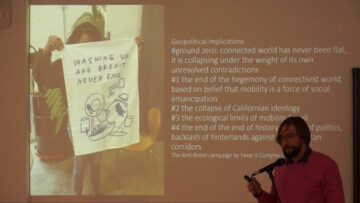

For example, on the 1st of September 2019, the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw will open the exhibition Never Again, which will revisit the complicated legacy and current iterations of anti-fascist struggles in art, featuring well known examples of Popular Fronts and Berlin dada of 1930s, but also critically discuss post-war instrumentalisation of anti-fascism by communist propaganda. One of the main ancillary public events related to this exhibition is an international summit Internationalism after the End of Globalisation, that we co-curate with Jesus Carillo and Sebastian Cichocki. As curators we posit that “responding to the recent revival of the fascist threat” implicates finding “new modes of artistic internationalism, embedded in the ongoing, democtratic struggles for climate, economic, gender, and racial justice.” The ambition of this summit is to analyse fascism as an aftereffect of failed, neoliberal globalisation, which threatens the very existence of progressive cultural institutions. Much have been said about the failures of globalisation, especially in wake of the financial crisis of 2000s and subsequent austerity. The fascist tremors are caused by seismic changes in geopolitics. The transition of the centres of accumulation south- and east-wards, has a double effect. On the hand, it undermines democratic public spheres in the Former West, already weakened by neoliberal onslaught. Paradoxically though, in countries like Poland, an advance in global logistical chains underpins the revival of national pride that can easily descend into an outright nationalism, authoritarianism, or even fascism. The summit is motivated by a conviction that one can only respond to this authoritarian double bind the by reviving progressive forms of internationalism, referring to the redemptive legacy of Communist International, Popular Fronts against War and Fascism, Non-aligned Movement, and the most recent project of alter-global movement-of-movements, hat struggled for more just, equal, and inclusive international order.

For an art worker the central question remains how to repurpose artistic idioms, subjectivitities, institutions, and their connections as potential contributors to an unfinished project of other, more just and equal globalisation. This rethinking should be radical, i.e. addressing the roots of a problem at hand, considering fascism not as a passing fashion or a temporary aberration, but rather as an apt expression of forces unleashed by the failed project of neoliberal globalisation. Faced with fascist conundrum, it would be futile to simply reiterate a globalist credo of contemporary art, in the period of long 1990s considered as an unquestionable modernising and liberalising force, a global connector and attractor of wealth and creativity.

Unfortunately, after twenty years of witnessing an unprecedented expansion of global artistic networks, we are all challenged with the authoritarian backlash of an equal scale. This rethinking cannot rely on a nostalgy for to a convivial form of a social-democratic welfarism and subsequent institutional models, neither in nor beyond art. The diminishing tax base in many Western countries puts institutions under strain, eroding remains of democratic public spheres, while the authoritarian movements in eastern and southern states thwart the democratic ambitions of local progressive institutions. In the same time, the market-oriented artistic circulation should be considered as part of the problem and not its solution. The speculative art market and biennale value chain far too often peddle capitalist realism, contributing to the atrophy of political and artistic imagination, that strengthen neoliberal hegemony, and create a power vacuum filled with the fascist imaginary. To counter this tendency, it is important to engender new artistic institutions of the common, embedded in the legacy of progressive internationalism, by collectively drawing from the previous research of L’internationale into constituencies, commons, geopolitics, uses of art, and to expand on both theoretical underpinnings and practicalities of organising an international confederation of civic artistic institutions.