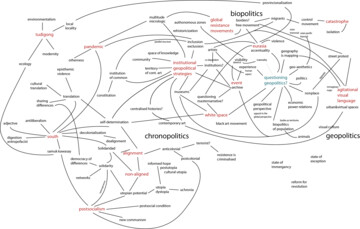

Despite many claims to the contrary, postsocialism and postcommunism should not be considered synonymous. Socialism may have been a political philosophy that communist parties in various parts of the world claimed (however inaccurately) to promote, but it was – perhaps most importantly – a philosophy of great relevance beyond communist governments as well. Its politics have long underpinned broader oppositions to capitalism and the oppression it can engender, whether in “east” or “west”, “north” or “south”, and have sought instead equitable redistributions of wealth across society and societies. Its politics have equally informed the rejection of privatised finance as our lingua franca – the “financialisation” of discourse, of social relations, of being characteristic of neoliberalism – and instead supported different ways of imagining international and geopolitical connections. We might recall how the first constitutions of many decolonising states (across Africa and South Asia especially) were explicit in their socialist ambitions for their new nations, as were the political ambitions of the third world international and of the non-aligned movement.

To limit postsocialism to what has happened in postcommunist states, and especially to conditions in Central and Eastern Europe, is thus to ignore its more properly international scope and its broader struggles against the neoliberal revolutions. Postsocialism arguably relates as much to the pressures on social democracies and welfare states in Scandinavia, in Western Europe or Australasia, and to the 20th century histories after independence in India or Ghana or Angola, as to the conditions of postcommunist Europe. As such, postsocialism suggests an important international connectedness in an age of globalization – albeit a connectedness that contains within it senses of the past and the future that differ from the more amnesic frameworks (or opportunisms) connoted by globalization. To speak of postsocialism, then, rather than neoliberalism or globalization per se, is to remind us of what has supposedly been lost since the 1980s, but which may still resonate some 30 years later, and to assert contemporary perspectives and historical trajectories that lie beyond those of the North Atlantic, that have largely been marginalised after socialism’s apparent collapse.

To insist on the social rather than the individual, and on translocal solidarities rather than global competition: if these are some of the cornerstones for more viable and more sustainable geopolitics today, and I think they are, then how might the various politics, aesthetics and ideas developed during socialism, or for socialism, respond to our condition today? What might it mean, for instance, to be “nonconformist” or even “dissident” (for all the problems associated with those monikers) in our supposedly post-ideological contemporaneity, and who might be the progenitors of these politics? And can solidarities across both space (geopolitics) and time (chronopolitics) engage with current and imminent crises that have little respect for national and political borders: from refugee crises, to the financialisation of subjectivity (perhaps of everything), and environmental catastrophe? Indeed, can solidarity re-emerge as a significant politics without thinking of socialism, its aftermath and its lingering potentials?